Apical rocking (ApR) and septal flash (SF) evaluated using echocardiography are mechanical consequences of left bundle branch block. Their presence is associated with effectiveness after cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and better prognosis. The aim was to analyze the relationship between ApR and SF before CRT and the outcomes.

MethodsRetrospective observational registry of 96 patients treated with CRT. ApR and SF were visually assessed by readers blinded to the CRT outcomes. The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause death and heart failure hospitalization.

ResultsApR or SF were present in 55% of the patients before CRT. At baseline, patients with ApR or SF were younger and had lower hemoglobin levels. The median follow-up was of 42 months. Composite endpoint incidence rate of the was 1.22 for 100 patients/year. The composite endpoint was significantly lower in the ApR or SF group as well as the heart failure hospitalization (17 vs 49%; P=.001). This group also improved the number of meters walked at the six-minute walking test (median [p25–p75] 61m (0–101) vs 6 (−11–37); P=.054) and the rate of CRT echocardiographic super-responders (26.5% vs 5.4%; P=.009). In multivariate analysis, the presence of Ap-Rock or SF (hazard ratio, 0.36; 95%CI, 0.15-0.86; P=.019), female sex, hemoglobin, and logarithm N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (logNT-proBNP) were associated with the composite endpoint.

ConclusionsSF or ApR were present before the biventricular pacemaker implantation in more than half of the patients with CRT indication and were associated with lower all-cause mortality and heart failure hospitalization and improved functional status and left ventricle ejection fraction at follow-up.

El apical rocking (ApR) y el septal flash (SF) son consecuencias mecánicas del bloqueo de rama izquierda. Su presencia se asocia con mejor pronóstico tras la terapia de resincronización cardiaca (TRC). Analizamos la relación entre ApR y SF, y los resultados tras la TRC.

MétodosRegistro observacional retrospectivo de 96 pacientes tratados con TRC. Lectores cegados a la respuesta evaluaron el ApR y el SF. El objetivo primario fue un compuesto de muerte por cualquier causa y hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca.

ResultadosEl ApR o el SF estaban presentes en el 55% de los pacientes antes de la TRC. Los pacientes con ApR o SF eran más jóvenes y con menores niveles de hemoglobina. La mediana de seguimiento fue de 42 meses. La tasa de incidencia de muerte o ingreso por insuficiencia cardiaca fue de 1,22 por cada 100 pacientes/año. En el grupo ApR o SF se observó una reducción del objetivo primario y de la hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca (17 frente al 49%; p=0,001). También mejoraron los metros caminados en la prueba de 6 minutos (mediana [percentil 25-percentil 75] 61m (0 a 101) frente a 6 [–11-37]; p=0,054) y la tasa de superrespondedores ecocardiográficos (26,5 frente al 5,4%; p=0,009). En el análisis multivariado, la presencia de Ap-R o SF (hazard ratio= 0,36; IC95%, 0,15-0,86; p=0,019), sexo femenino, el nivel de hemoglobina y logaritmo péptido natriurético de tipo b N-terminal pro (logNT-proBNP) fueron las variables relacionadas de manera estadísticamente significativa con el objetivo primario.

ConclusionesSe documentó SF o ApR en más de la mitad de los pacientes con indicación de TRC y se asocian con menor mortalidad y hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca, y mejor estado funcional y función ventricular en el seguimiento.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) achieved by implantation of a biventricular pacemaker is recommended for symptomatic patients with heart failure (HF) in sinus rhythm with a QRS duration≥130ms and left bundle branch block (LBBB) QRS morphology and with left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF)≤35% despite optimal medical therapy to improve symptoms and reduce morbidity and mortality. In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), it is essential to provide a strategy to ensure biventricular capture.1 The response to CRT when there is electrical asynchrony is known. However, identifying patients who will be responders to this therapy is challenging. The initial studies performed to demonstrate mechanical asynchrony by echocardiography did not reveal its usefulness in predicting response to CRT, usually defined as left ventricle reverse remodeling. Therefore, echocardiography assessment of left ventricular asynchrony has no additional benefit over electrocardiogram alone.2 Although rather infrequent, CRT implantation is associated with short-term and long-term complications. Indeed, a European survey showed that the peri-procedural complication rate was 5.1%, and major adverse events occurred in 5.4% of upgraded and 4.4% in de novo CRT recipients.3 Identifying patients with a high likelihood of being responders is crucial, so CRT is to be offered to this group, maximizing the risk-benefit profile of this therapy.

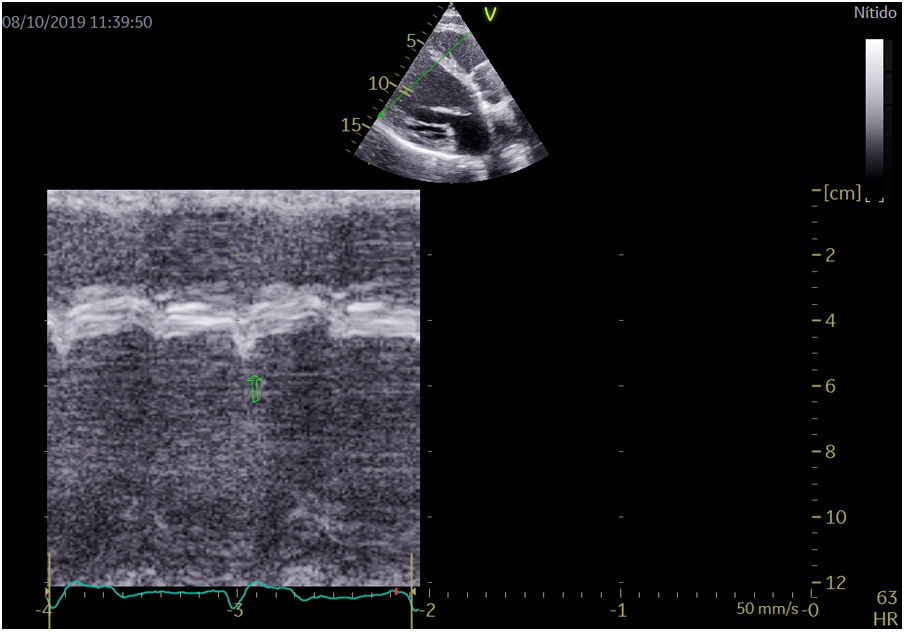

The early inward motion and thickening/thinning of the ventricular septum associated with LBBB, called septal flash (SF),4 and the apical rocking (ApR) are mechanical consequences of LBBB. Both can be evaluated visually using M-mode echocardiography and results from an imbalance of myocardial function due to intraventricular conduction delays, regional damage, or both.5 Some data suggest that their presence, unlike classical echocardiographic parameters, can indicate effectiveness after CRT, and it seems to be associated with a better prognosis.6 Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the relationship between the ApR and SF presence before the biventricular pacemaker implantation and the outcomes after CRT in a non-selected chronic heart failure population.

MethodsStudy design and data collectionWe retrospectively analyzed data from 96 patients with chronic heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of ≤35%, QRS duration≥130ms, and symptoms related to heart failure despite optimal pharmacological therapy treated with CRT at the Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain. QRS duration≥130ms was chosen according to the European HF guidelines.1 We consecutively enrolled patients from July 2010 to January 2020. No patients were excluded. As part of standard practice, all patients followed a protocol that included echocardiographic and blood test parameters, 6-minute walking test, and functional class assessments at baseline and 12-month follow-up after CRT implantation. However, clinical practice sometimes made it impossible to assess all the parameters in all patients at both time points. Data were collected retrospectively. Two readers visually evaluated the presence of ApR and SF. Both readers are cardiologists who specialized in echocardiography and were blinded to the outcomes after CRT. The QRS duration was automatically calculated as the time from the start of the Q wave to the end of the S wave. All ECGs were done with the Philips PageWriter TC30 Cardiograph (Koninklijke Philips, The Netherlands).

Two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiogram images were obtained using a Vivid E95 (GE Healthcare, Norway) and were recorded and analyzed offline using commercially available software (EchoPac v.201, GE Healthcare, Spain). Left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters were measured in the parasternal long-axis view. The SF and ApR were visually assessed in apical 4 chamber view. LVEF was subsequently calculated as follows: LVEF=[(LVEDV−LVESV)/LVEDV]×100 using Simpson's biplane formula. ApR was positive if a short septal movement of the apex due to early contraction of the septum in systole and a long posterior movement to the lateral side during ejection due to late lateral contraction caused by LBBB was present.7 SF was positive if a rapid short inward movement of the basal ventricular septum was present in the isovolumetric systolic period7 (Fig. 1; video 1 of the supplementary data). Both movements can be easily feasible with simple eyeballing during echocardiography. In a previous study,8 the average agreement for the presence of septal flash was 68% (kappa range 0.16–0.46) and for apical rocking 70% (kappa range 0.25–0.69). Our study showed a 71.4% agreement in apical rocking (kappa 0.39) and 74% agreement in septal flash (kappa 0.5).

The presence of LVEF>50% at follow-up was the criterion to define super-response to CRT.9

Our study aimed to analyze the baseline characteristics of the whole cohort and compare the outcomes after CRT between the groups with and without ApR or SF (ApR/SF) before the biventricular pacemaker implantation. The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause death or heart failure (HF) hospitalization. As secondary study endpoints, we assessed the impact of the intervention in terms of exercise capacity measured by the 6-minute walking test (6MWT) and the percentage of CRT echocardiographic super-responders.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were summarized as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on the variable distribution. Patients’ characteristics were compared between the presence of ApR/SF and outcome status categories (death or HF hospitalization) by Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and by Pearson's chi-squared test for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates were used to calculate the observed cumulative incidence of the composite endpoint (death or HF hospitalization), and the log-rank test tested statistical significance. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of death or HF hospitalization for ApR/SF presence was analyzed using Cox proportional hazard models. The models were adjusted for potential confounders selected by stepwise forward inclusion among patient characteristics significantly associated with the presence of SF/ApR and the composite endpoint. We included variables with P<.05. We decided to add atrial fibrillation to the model since it has also been associated with prognosis in many studies. Its prognostic role when analyzing SF/ApR is not fully known. We assessed the correlation between LBB and QRS>150ms with SF/ApR. Only QRS>150ms had a weak positive correlation with SF or ApR (Spearman's rho=0.206; P=.044). There was no correlation between LBB and QRS>150ms (Spearman's rho=0.045; P=.663) nor between LBBB and SF or ApR (Spearman's rho=0.169; P=.105). Therefore, considering this finding and the fact that the ESC HF guidelines base the CRT indication on a QRS>150ms, we included this parameter in the analysis. The number of events per degree of freedom was fairly small, and below the rule of thumb established at 10 events per variable. However, the convenience of this rule of thumb has been largely discussed in the literature in recent years.10 Thus, the final model was adjusted for age, baseline ApR or SF, estimate glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin, atrial fibrillation, NT-proBNP, and QRS duration>150ms. The proportional hazard assumption, checked by examining residuals (for overall model and variable by variable), was not violated. P values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All tests were performed with SPSS version 25 (IBM SPSS v. 25, United States).

Ethics considerationsOur institutional Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol (number 2019/8830) and waived the need for written informed consent due to its retrospective nature. The investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

ResultsBaseline characteristics of the 96 patients included in the analysis are summarized in Table 1. De novo CRT implantation was performed in 91 patients, 5 patients (5.2%) underwent upgrade to CRT. Briefly, ApR or SF was present in 55% of the patients before CRT, but both were only present in 34.4% of patients. In the ApR/SF group, 88.7% had SF, 71.7% had ApR, and 62.3% had both. The baseline characteristics and outcomes of SF and ApR are described in Table 1 of the supplementary data.

Baseline characteristics of the whole cohort and by the presence of apical rocking or septal flash.

| All patients(n=96) | ApR or SF(n=53) | No ApR or SF (n=43) | P-value | N (missing) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 26 (27.1) | 15 (28.3) | 11 (25.6) | .77 | 96 |

| Age, years | 67.5±10.3 | 69.3±8.9 | 64.8±11.5 | .03 | 96 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 34 (35.8) | 16 (30.2) | 18 (42.9) | .20 | 95 (1) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 30 (32.3) | 18 (13.5) | 12 (28.6) | .49 | 93 (3) |

| LBBB | 77 (82.8) | 46 (88.5) | 31 (75.6) | .10 | 93 (3) |

| QRS≥150ms | 72 (75) | 44 (83) | 28 (65.1) | .044 | 96 |

| QRS duration, ms | 166.1±24.5 | 167.1±21.7 | 163.7±28.2 | .51 | 96 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 118.2±17.7 | 118.6±18.7 | 118.5±17.2 | .97 | 96 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 68.7±13.6 | 68.4±13.1 | 69.9±14.3 | .60 | 96 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 57.8±17.7 | 57.5±17.0 | 57.4±18.7 | .97 | 89 (7) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.1±1.7 | 12.7±1.9 | 13.6±1.6 | .01 | 86 (10) |

| NYHA class | 2.2±0.5 | 2.2±0.5 | 2.3±0.5 | .49 | 96 |

| 6MWT, m | 339.4±96.2 | 324.3±100.7 | 360.1±92.4 | .19 | 52 (44) |

| LVEF, % | 28.3±5.6 | 28.9±5.4 | 27.8±6.0 | .34 | 96 |

| LVEDD, mm | 63.7±8.0 | 62.6±7.7 | 65.0±8.5 | .16 | 96 |

| LVESD, mm | 53.6±9.0 | 52.7±8.8 | 54.8±9.5 | .29 | 96 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 2062 [1017–3633] | 1559 [608–3653] | 2316 [1240–3613] | .21 | 91 (5) |

| Septal flash | 47 (49.0) | 47 (88.7) | 0 | <.001 | 96 |

| Apical rocking | 38 (39.6) | 38 (71.7) | 0 | <.001 | 96 |

| Septal flash and apical rocking | 33 (34.4) | 33 (62.3) | 0 | <.001 | 96 |

Data are n (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. 6MWT, six minutes walking test; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEDD, left ventricle end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricle end-systolic diameter; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Patients with ApR/SF at baseline were younger, had more frequently a QRS≥150m (although the mean QRS was not statistically different), and had lower hemoglobin levels. There were no other significant differences at baseline. There were no differences in the prevalence of SF, ApR, or both between men and women (the supplementary data). Most of the patients were Caucasian.

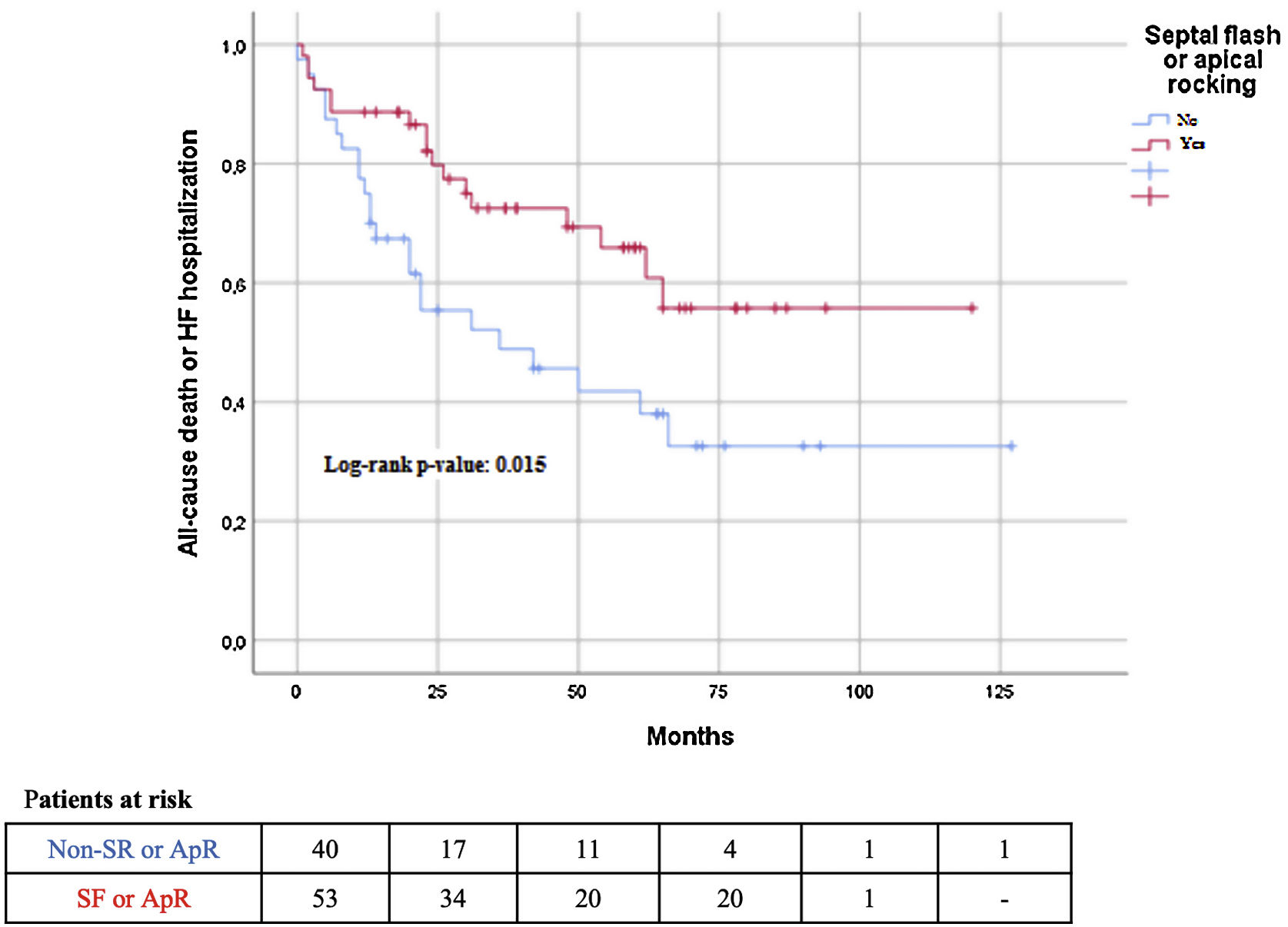

The median follow-up was 42 (25–65) months. During follow-up, 31 (32.5%) patients died, and 30 (31.3%) patients were admitted to the hospital due to worsening of HF. The composite endpoint outcome of death and HF hospitalization occurred in 45% of the patients. All-cause mortality was not significantly lower in the ApR/SF group; however, the composite outcome of HF hospitalization or all-cause death was significantly lower in patients with ApR/SF than in patients without ApR/SF (32% vs 60%; P<.001). The same result was observed in terms of HF hospitalization (17% vs 49%; P=.001) (Table 2; Fig. 2). Patients with ApR/SF significantly improved the number of meters walked at the 6MWT (median [percentile 25-percentile 75) 61m (0–101) vs 6 (−11–37)m; P=.054; and had an increase of at least 50m more frequently 60% vs 19%; P=005), and there was a significantly higher percentage of CRT echocardiographic super-responders (defined as LVEF>50%) (Table 2).

Outcomes of the whole cohort and by the presence of septal flash or apical rocking.

| All patients(n=96) | ApR or SF(n=53) | No ApR or SF(n=43) | P-value | N (missing) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement in >50m in 6MWT | 19 (41.3) | 15 (60.0) | 4 (19.0) | .005 | 46 (50) |

| Improvement of at least 1 NYHA class | 31 (36) | 21 (42.9) | 10 (27.0) | .13 | 86 (10) |

| LVEF>50% at 1-year | 15 (17.4) | 13 (26.5) | 2 (5.4) | .009 | 86 (10) |

| HF hospitalization or death | 43 (44.8) | 17 (32.1) | 26 (60.5) | .005 | 96 |

| Death | 31 (32.5) | 14 (26.4) | 17 (39.5) | .17 | 96 |

| HF hospitalization | 30 (31.3) | 9 (17.0) | 21 (48.8) | .001 | 96 |

Data are n (%). 6MWT, 6-minutes walking test; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

As expected, patients with the composite endpoint had a significantly worse renal function, lower hemoglobin level, and higher NT-proBNP level at baseline. Furthermore, fewer patients improved by >50 meters in the 6MWT and reached LVEF>50% at 1-year follow-up compared with patients without the composite endpoint (Table 3). The presence of SF and the presence of ApR/SF between the groups with and without the composite endpoint were significantly different (31% vs 60%; P=.02; and 40% vs 68%; P=.005; respectively) (Table 3).

Baseline characteristics by the presence of composite endpoint (all-cause death or HF hospitalization).

| Death or HF hospitalization (n=45) | Event-free (n=51) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 9 (20) | 17 (30.9) | .22 |

| Age, years | 68.9±9.6 | 66.5±10.8 | .24 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 19 (43.2) | 16 (29.1) | .14 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16 (36.4) | 15 (29.4) | .47 |

| LBBB | 36 (83.7) | 44 (81.5) | .77 |

| QRS≥150ms | 29 (67.4) | 43 (81.1) | .12 |

| QRS duration, ms | 165.1±28 | 166.8±21.4 | .73 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 115.2±15.6 | 120.7±19.0 | .12 |

| Heart rate, beats per minute | 68.7±14.2 | 68.7±13.1 | .99 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 52.2±16.3 | 61.9±17.3 | .008 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.6±1.8 | 13.5±1.6 | .01 |

| NYHA class | 2.36±0.53 | 2.13±0.47 | .025 |

| 6MWT, m | 342.2±99.3 | 336.9±94.9 | .84 |

| LVEF, % | 27.4±5.3 | 29±5.8 | .13 |

| LVEDD, mm | 65.1±8.3 | 62.3±7.6 | .12 |

| LVESD, mm | 54.8±8.5 | 52.5±9.3 | .2 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 2998 [1654–6690] | 1288 [530–2551] | <.001 |

| Septal flash | 14 (31.1) | 33 (60) | .02 |

| Apical rocking | 15 (33.3) | 23 (41.8) | .68 |

| Septal flash and apical rocking | 12 (26.7) | 21 (38.2) | .48 |

| Apical rocking or septal flash | 17 (39.5) | 36 (67.9) | .005 |

| Improvement in>50m in 6MWT | 2 (9.5) | 17 (65.4) | <.001 |

| Improvement of at least 1 NYHA class | 14 (35.9) | 35 (63.6) | .008 |

| LVEF>50% at 1-year | 3 (8.1) | 12 (23.1) | .055 |

Data are n (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. 6MWT, 6minutes walking test; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDD, left ventricle end-diastolic diameter; LVESD, left ventricle end-systolic diameter; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Results of both univariate and multivariate analyses of the association between ApR or SF and the composite endpoint are summarized in Table 4. In univariate analyses, the composite endpoint was associated with the absence of ApR/SF, higher renal impairment, QRS duration>150ms, NT-proBNP level, and lower hemoglobin. In multivariate analysis, the presence of ApR or SF (HR, 0.36; 95%CI, 0.15–0.86]; P=.019), female sex, hemoglobin and logNT-proBNp were associated with the composite endpoint. When analyzed separately (SF/ApR and non-SF/ApR), the only baseline characteristics associated with the endpoint were hemoglobin and NT-proBNP levels in both groups and estimated glomerular filtration rate in the SF/ApR group.

Hazard ratios of death or heart failure hospitalization for baseline apical rocking or septal flash adjusted for potential confounders.

| Univariate HR (95%CI) | Adjusted HR (95%CI)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per every year) | 1.03 (0.99–1.06), P=.14 | 1.03 (0.98–1.09), P=.271 |

| Baseline SF/AR | 0.47 (0.25–0.88), P=.018 | 0.36 (0.15–0.65), P=.019 |

| eGFR (per every mL/min) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99), P=.012 | 1.0 (0.98–1.03), P=1.0 |

| Hemoglobin (per every g/dL) | 0.78 (0.63–0.93), P=.006 | 0.77 (0.60–0.97), P=.028 |

| LogNT-proBNP | 1.88 (1.41–2.52), P<.001 | 1.53 (1.05–2.2), P=.025 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.17 (0.62–2.19), P=.63 | 1.44 (0.6–3.4), P=0.42 |

| Baseline QRS duration>150ms | 0.52 (0.27–0.99), P=.046 | 0.62 (0.24–1.55), P=.30 |

Model adjusted for age, baseline ApR or SF, estimate glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin, atrial fibrillation, NT-proBNP, and QRS duration>150ms. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ApR, apical rocking; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; LogNT-proBNP, logarithm N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; SF, septal flash.

ApR or SF was present in 55% of the patients in our series. Ghani et al. described the presence of ApR in 45% of the patients undergoing CRT,11 while Gąsior et al. documented 28% of patients with SF.12 In the most extensive study, published by Stankovic et al., ApR and SF were observed in 64% and 63% of patients, respectively, and these patients were younger, more frequently female, had more often LBBB morphology, longer QRS duration, less ischemic disease, and less atrial fibrillation.4 With 55% of patients with asynchrony parameters, our study does not differ so much from these results. Several studies have also shown that SF or ApR and its relationship with remodeling are associated with the etiology of HF, with lower prevalence and LVEF improvement in ischemic patients.11,12 We did not see this difference in our series; the only significant differences we found between the groups with and without ApR/SF were age and hemoglobin level. However, our relatively small sample size might have modulated these results.

ApR/SF before CRT in this study was independently associated with a lower incidence of all-cause death or HF hospitalization during a follow-up of more than 3 years. This better prognosis is consistent with the studies by Stankovic et al. and Ghani et al.6,11 that showed a more favorable long-term survival after CRT when ApR or SF were present at baseline. Both studies had a follow-up similar to ours, with a 46 to 5.2 years median period. However, HF hospitalization was only included in the composite outcome in the study by Ghani et al.11 Interestingly, the population included in that study was comparable to ours and showed a 21% mortality rate and a 21% HF hospitalization.

The CRT benefit identified in patients with ApR/SF was observed in terms of survival and hospitalizations and in terms of exercise capacity measured by the 6MWT. In patients with a 6MWT available at baseline and at 1-year follow-up, 60% of patients with ApR/SF improved more than 50 meters, whereas it was only true in 19% of patients without ApR or SF (P=.005). CRT response is usually also evaluated by the presence of reverse LV remodeling, defined by changes in LV end-systolic volume, LVEF at 3–6 months after CRT implantation or both. The presence of LVEF>50% at follow-up has been proposed as a criterion for super-response,9 and the long-term outcome of super-responders of CRT is excellent.13 We observed super-response to CRT in the present study in 26% of the patients. The presence of ApR/SF before CRT implantation was associated with a super-response defined as LVEF recovery (LVEF>50%). This result is consistent with other studies that showed that ApR was independently associated with super-response to CRT.14

Finally, the early CRT studies suggested that CRT might not be effective for AF patients.15 However, the Certify trial showed the importance of achieving a high biventricular pacing percentage, preferably by atrioventricular junction ablation. The clinical outcome after CRT for patients with AF treated with atrioventricular junction ablation is similar to that observed in sinus rhythm.16 In our study, 32% of patients had AF as a baseline rhythm without differences between both groups. The presence of AF did not limit the echocardiographic assessment of SF and ApR. Interestingly, the better outcomes observed in the group with baseline ApR/SF after CRT were also present in patients with AF. These findings are similar to those in the study by Gabrielli et al., where they describe that the presence of SF at baseline is associated with a higher likelihood of CRT response in HF patients with long-standing AF.17

LimitationsThe present clinical study has certain limitations. The main ones were its relatively small size and the retrospective nature of the analysis. Moreover, the interpretation of changes in 6MWT distance is limited by the number of missing data at baseline or follow-up. It has been described that the correction of ApR and SF with CRT has been associated with remodeling and favorable long-term survival.6

ConclusionsMore than half of the patients with CRT indication who underwent biventricular pacemaker implantation had ApR or SF at baseline. Still, demographic and clinical characteristics could not allow to identify them. The presence of ApR or SF was associated with lower all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization and improved functional status and LVEF at follow-up. These results highlight the importance of carefully assessing the presence of ApR and SF in all patients irrespective of clinical characteristics to identify patients who will present a better response to CRT.

- -

The identification of potential responders to CRT remains difficult. The presence of Ap-Rock and SF before CRT, unlike classical echocardiographic parameters, can indicate effectiveness after CRT, and it seems to be associated with a better prognosis.

- -

For both echocardiographic parameters, it has been described that the quantitative and visual assessment is easy, clinically feasible, and reproducible.

- -

In our study, the presence of ApR or SF was associated with lower all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization and improved functional status and LVEF at follow-up.

- -

Given the challenge in selecting patients, we believe that these results add information to better understand the significance of ApR and SF in identifying patients responding to cardiac resynchronization therapy.

This study received no funding.

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, methodology, validation, review draft and editing, project administration, S. Ruiz Bustillo and N. Farré; software, A. García Durán and F. Escalante; formal analysis, N. Farré; investigation, S. Ruiz Bustillo, A. García Durán, A. Mas-Stachurska, E. Vallès, L. Belarte Tornero and N. Farré; resources, N. Farré and A. Mas-Stachurska; data curation, A. García Durán, F. Escalante, A. Calvo Fernández, J. Jimenez López, E. Solé González, R. Morales Murillo, S. Ruiz Bustillo and N. Farré; writing original draft preparation, S. Ruiz Bustillo; visualization, A. García Durán, A. Calvo Fernández, A. Mas-Stachurska, F. Escalante, E. Vallès, J. Jimenez López, L. Belarte Tornero, Sandra Valdivielso More, E. Solé González, R. Morales Murillo, J. Martí Almor; supervision, N. Farré. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.