Oral anticoagulation therapy is prescribed to most patients with atrial fibrillation. The main limitation of anticoagulant treatment is the occurrence of bleeding episodes. We sought to assess the type of hemorrhages and mortality in patients anticoagulated for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

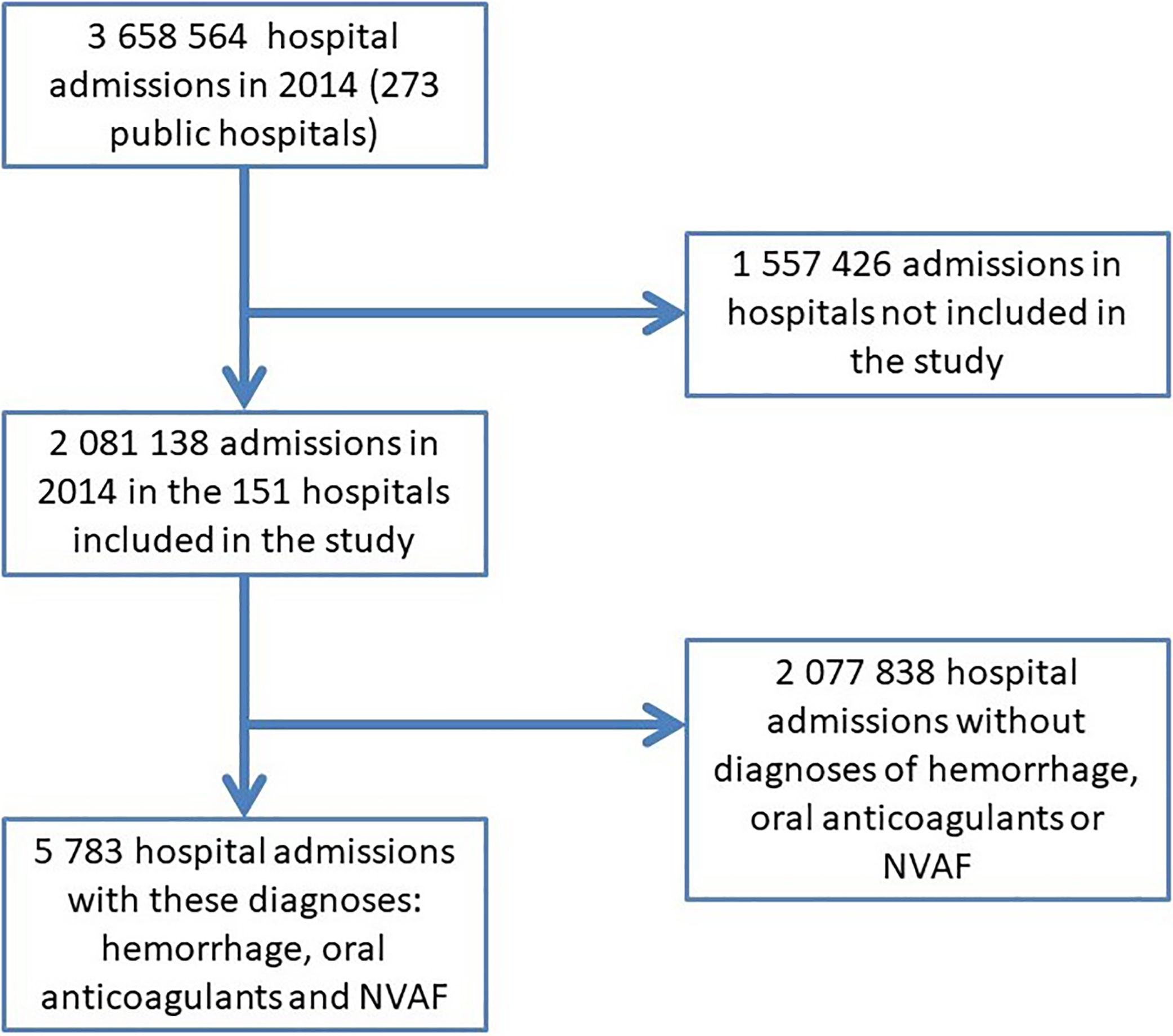

MethodsObservational retrospective study analyzing 2081138 hospitalization reports from 2014 corresponding to 151 hospitals of the Spanish National Health System. Patients were selected with the diagnosis of hemorrhage, nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, and oral anticoagulation.

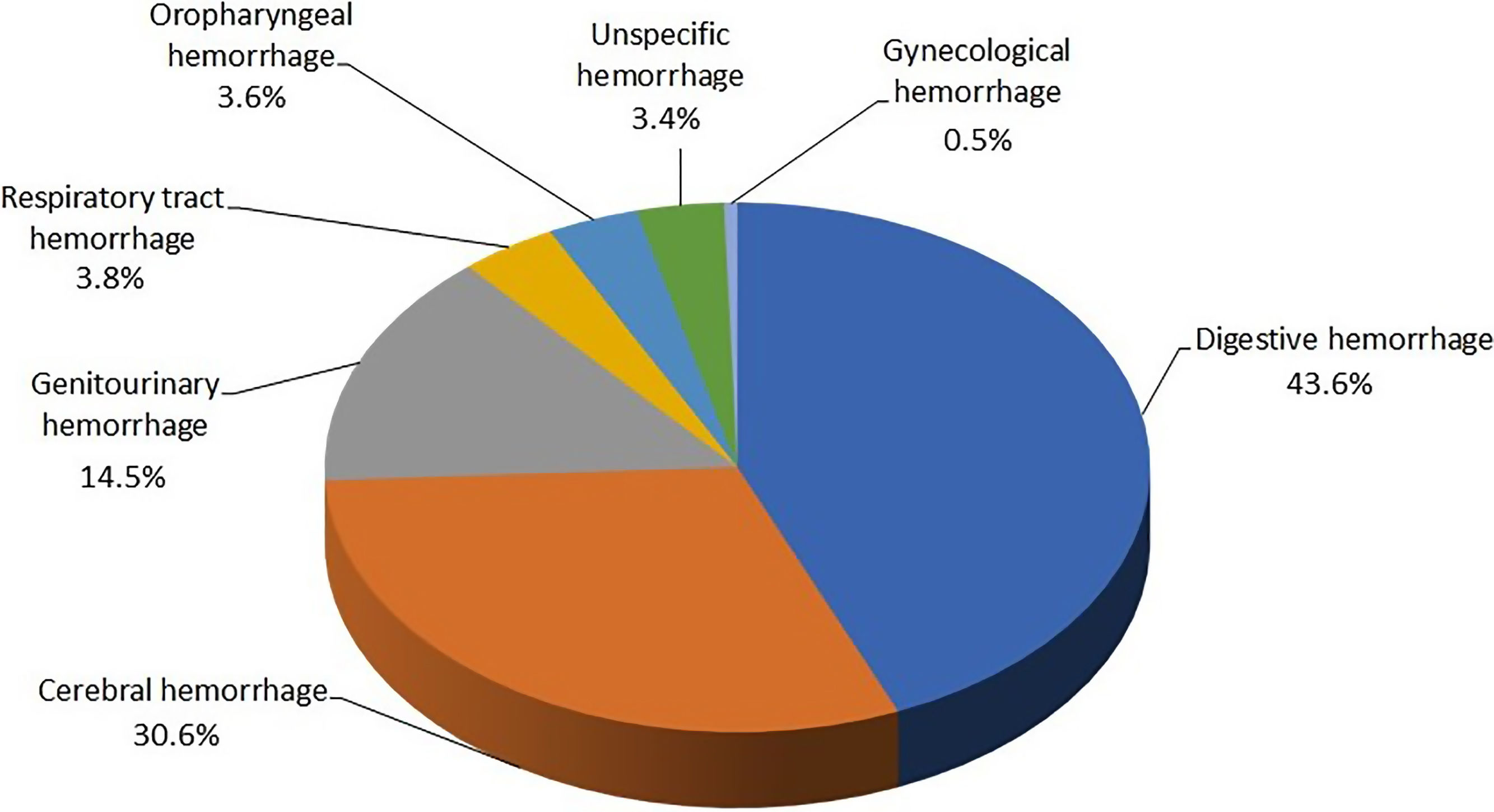

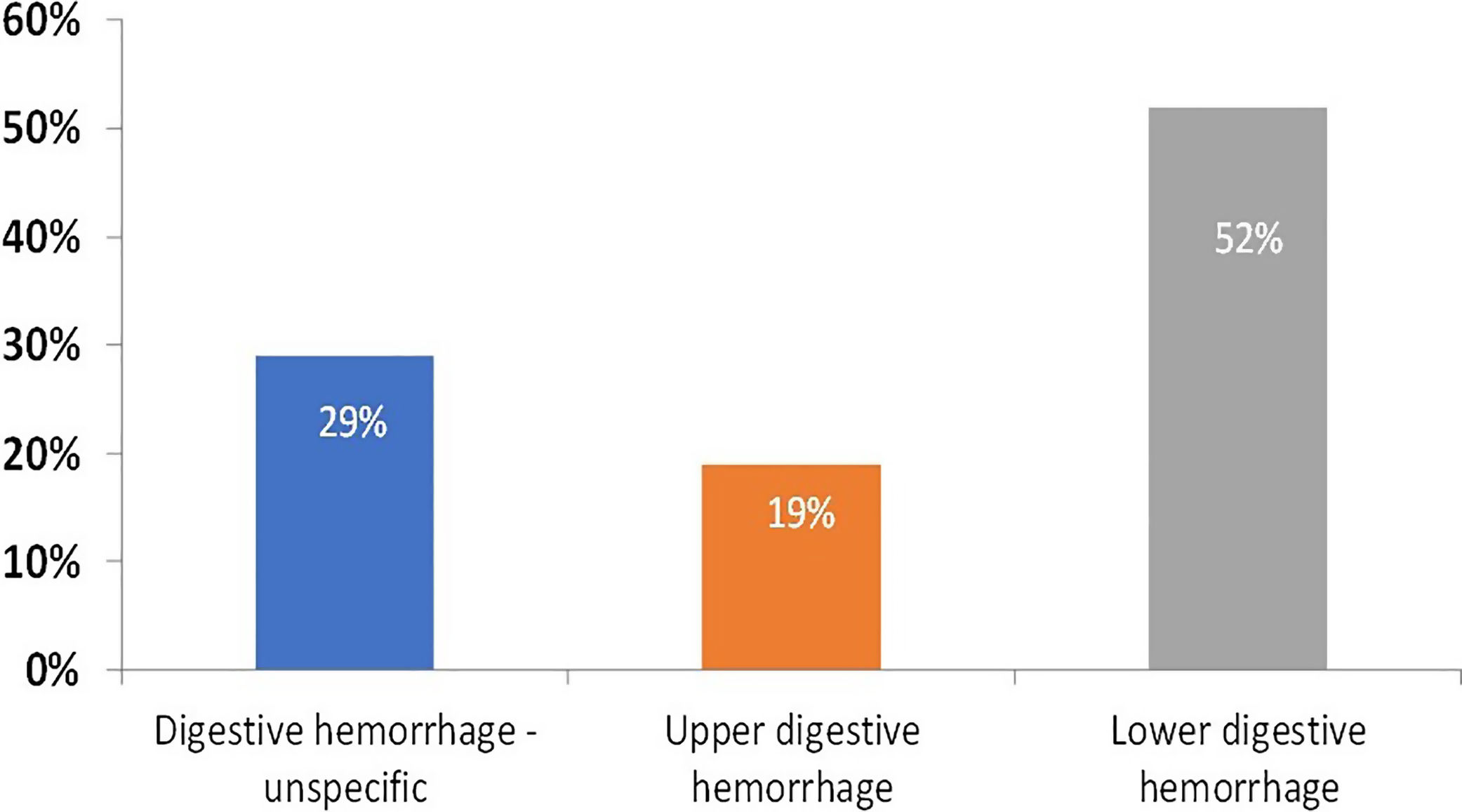

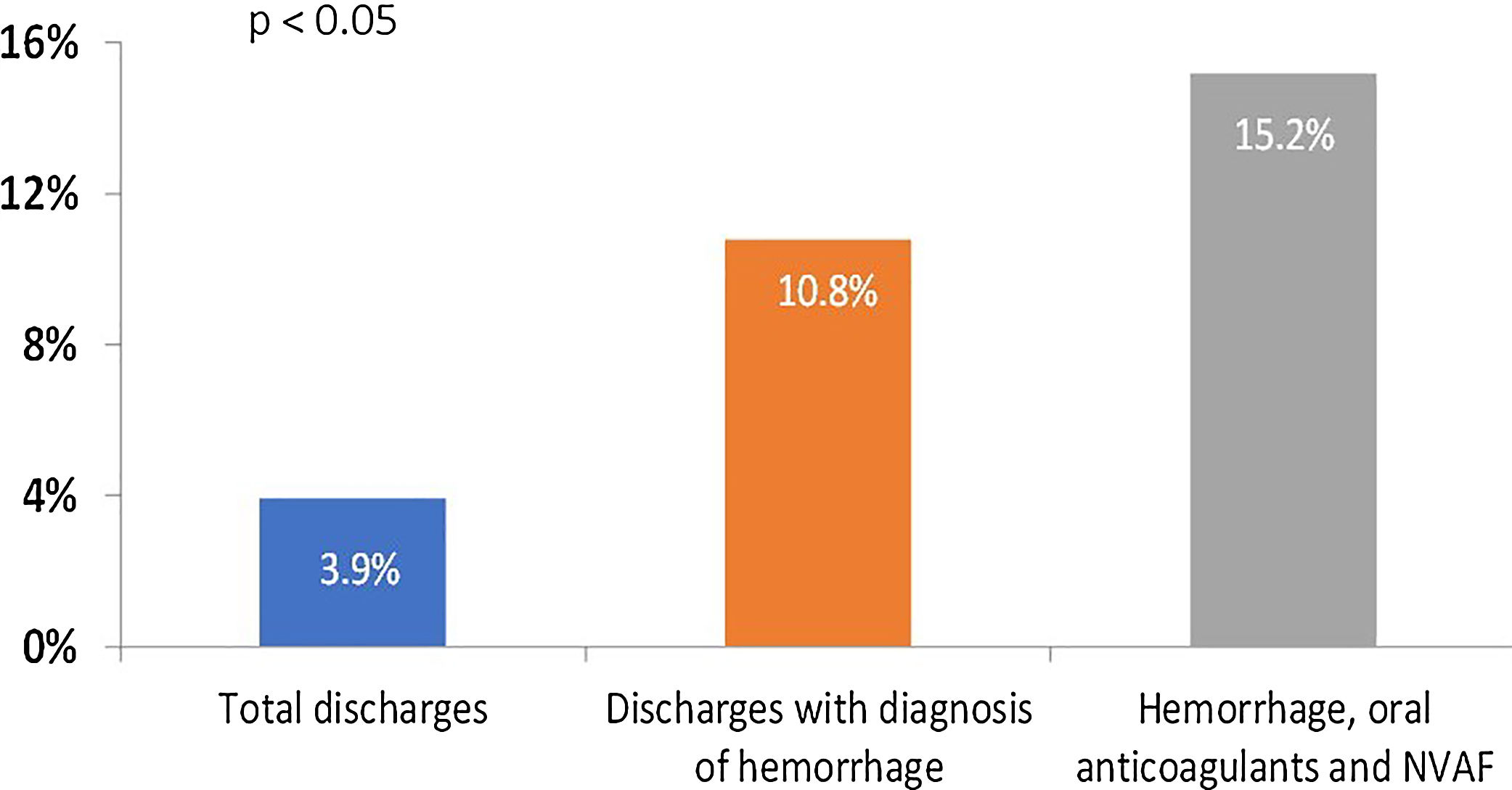

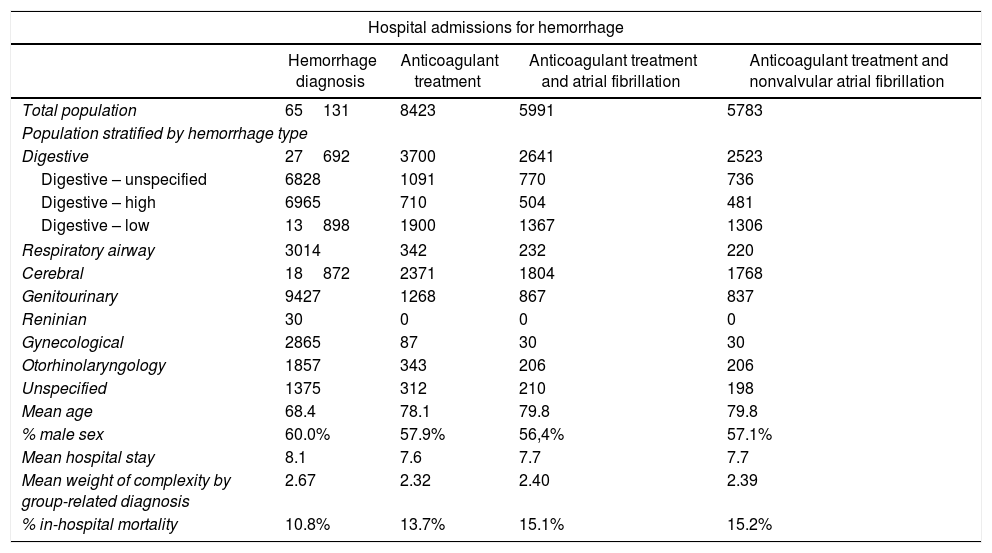

ResultsA total of 5783 hospitalizations were analyzed. Most hemorrhages were digestive (43.6%), followed by cerebral (30.6%). Among the digestive, only 27% were high. Mean age was 79.8 years, 57.1% were males, the mean hospital stay was 7.7 days. Complexity assessed by the mean diagnostic related group was 2.39 (versus 1.83 of the total hospitalizations). In-hospital mortality was 15.2% versus 10.8% of the hospitalization for hemorrhages and 3.9% of the total hospitalizations (P<.05).

ConclusionsHemorrhages in patients anticoagulated for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation have a high sociosanitary impact. The most frequent hemorrhages were digestive, only a fourth part of them was high. A third of hemorrhages were cerebral. In-hospital mortality in this population was high.

La mayoría de los pacientes con fibrilación auricular reciben tratamiento anticoagulante oral. Las principales complicaciones del tratamiento anticoagulante son los episodios de sangrado. Nuestro objetivo fue determinar el tipo de hemorragias y la mortalidad de los pacientes anticoagulados por fibrilación auricular no valvular.

MétodosSe trata de un estudio observacional retrospectivo, en el que se analizaron los informes de alta de 2.081.138 hospitalizaciones en 2014, de 151 hospitales del Sistema Nacional de Salud de España. Se seleccionó a los pacientes con los diagnósticos de hemorragia, fibrilación auricular no valvular y anticoagulación oral.

ResultadosSe analizaron un total de 5.783 hospitalizaciones. Las hemorragias más frecuentes fueron de origen digestivo (43,6%), seguido de cerebral (30,6%). De las hemorragias digestivas, únicamente 27% fueron altas. La edad media fue de 79,8 años, el 57,1% fueron varones y la estancia media fue de 7,7 días. La complejidad valorada mediante el grupo relacionado con el diagnóstico fue de 2,39 (frente a 1,83 del total de hospitalizaciones). La mortalidad hospitalaria fue de 15,2%, frente a 10,8% de mortalidad entre los pacientes con hemorragias sin fibrilación auricular y 3,9% del total de hospitalizaciones (p <0,05).

ConclusionesLas hemorragias en pacientes con fibrilación auricular no valvular tienen un elevado impacto sociosanitario. Las hemorragias más frecuentes fueron de origen digestivo, y únicamente un cuarto de ellas fue alto. Un tercio de las hemorragias fue cerebral. La mortalidad hospitalaria en esta población fue elevada.

Atrial fibrillation is the most frequent sustained cardiac arrhythmia and the one with the greatest health impact in the United States and Europe. It is estimated to affect 4.4% of the population, although the figures vary depending on the methodology of the studies and the sample studied.1,2

The evolution of the patients with atrial fibrillation depends to a large extent on the possibility of presenting a thromboembolic complication. In patients with atrial fibrillation, the thrombotic risk should be calculated and in case of presenting thrombotic risk factors added to the arrhythmia itself, the initiation of anticoagulant treatment is recommended.3

The use of anticoagulant drugs leads to an increased risk of bleeding episodes.4 This fact conditions both the evolution of the patient and the attitude of doctors and patients toward the indication of anticoagulant treatment.5 We sought to assess the type of hospitalizations for hemorrhage in patients anticoagulated for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF), as well as their in-hospital mortality.

MethodsThis is a retrospective observational study evaluating hospitalizations during 2014 with the main diagnosis of hemorrhage and secondary diagnoses of oral anticoagulants and NVAF.

The data were taken from the hospitalization database of Iasist Inc, a professional health information services company. The database contains hospitalization data from 151 Spanish acute care hospitals of the National Health System representing 57% of the total annual acute hospitalizations of the National Health System. In 2014, there were 3658564 hospital admissions in the National Health System in Spain. Of those 2081138 were admissions in the 151 hospitals participating in the study. The final analysis was performed in the 5783 hospitalizations with diagnoses of hemorrhage, oral anticoagulant treatment, and NVAF (Fig. 1). Although these data do not correspond to a sample strictly designed to be statistically representative of the national hospitalization, given the territorial distribution of the hospitals, the inclusion of various levels of hospitals and the volume of existing data they constitute a good representation of the national activity of hospitalization. Thus it is an extrapolation to the casuistry of the 3658564 discharges in 2014 by the 273 acute public hospitals of the National Health System (Fig. 1).

The minimum basic data set represents the most reliable and updated standardized source of activity carried out by the hospitals of the Spanish National Health System. It is a set of clinical and administrative data of each episode of hospitalization attended in a hospital; collects information on the age and sex of the patients, the dates of admission and discharge, the circumstances of admission and discharge and the diagnoses and procedures of the episode coded by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (Supplementary data). The complexity of the hospitalization was assessed by means of the group related with the diagnosis. The diagnosis-related group is a system created to classify hospital cases and has been used for reimbursement issues and for complexity of the hospitalization.6

Hemorrhages were classified into 8 groups: digestive hemorrhage (distinguished between unspecific, upper or lower digestive hemorrhage), respiratory tract hemorrhage, cerebral hemorrhage, genitourinary hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhage, gynecological bleeding, oropharyngeal hemorrhage, and unspecific hemorrhage.

The following groups of antithrombotic agents were considered as oral anticoagulants: vitamin K antagonists, warfarin and acenocoumarol, dabigatran etexilate, direct inhibitors of factor Xa: apixaban and rivaroxaban.

The continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation and compared using the Student t test. The categorical variables are expressed by percentages and compared using the chi-square test. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsWe analyzed 5783 hospitalizations with the diagnosis of hemorrhage in patients treated with oral anticoagulants and with a diagnosis of NVAF.

The mean age of the study sample was 79.8 years and 57.1% were male. The average hospital stay was 7.7 days. The complexity of the hospitalization episodes determined by means of weight of diagnosis-related group was 2.40.

The most frequent origin was digestive hemorrhage (43.6%), followed by cerebral hemorrhages (30.5%) (Fig. 2). The distribution of digestive hemorrhages was as follows: 29% unspecified, 19% upper and 52% lower. Only 27% of the localized digestive hemorrhages were upper (Fig. 3).

In-hospital mortality was 15.2% (compared with 10.8% of all hemorrhages and 3.9% of total hospitalizations, P<.05) (Table 1) (Fig. 4).

Characteristics of the patients included in the study.

| Hospital admissions for hemorrhage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhage diagnosis | Anticoagulant treatment | Anticoagulant treatment and atrial fibrillation | Anticoagulant treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation | |

| Total population | 65131 | 8423 | 5991 | 5783 |

| Population stratified by hemorrhage type | ||||

| Digestive | 27692 | 3700 | 2641 | 2523 |

| Digestive – unspecified | 6828 | 1091 | 770 | 736 |

| Digestive – high | 6965 | 710 | 504 | 481 |

| Digestive – low | 13898 | 1900 | 1367 | 1306 |

| Respiratory airway | 3014 | 342 | 232 | 220 |

| Cerebral | 18872 | 2371 | 1804 | 1768 |

| Genitourinary | 9427 | 1268 | 867 | 837 |

| Reninian | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gynecological | 2865 | 87 | 30 | 30 |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 1857 | 343 | 206 | 206 |

| Unspecified | 1375 | 312 | 210 | 198 |

| Mean age | 68.4 | 78.1 | 79.8 | 79.8 |

| % male sex | 60.0% | 57.9% | 56,4% | 57.1% |

| Mean hospital stay | 8.1 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.7 |

| Mean weight of complexity by group-related diagnosis | 2.67 | 2.32 | 2.40 | 2.39 |

| % in-hospital mortality | 10.8% | 13.7% | 15.1% | 15.2% |

Our study shows that the most frequent source of bleeding is the digestive tract, followed by cerebral hemorrhages; and that patients anticoagulated for NVAF and hospitalized due to hemorrhages have a high in-hospital mortality.

Gastrointestinal bleedingAs in other studies, our results show the gastrointestinal tract as the most frequent origin of major hemorrhages. However, the location within the gastrointestinal tract has been different, with a lower percentage of upper digestive hemorrhages compared to what has been published by other groups.7 In the RELY study, 47% of major gastrointestinal hemorrhages were lower, compared with 53% of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages.8 In a subanalysis of the ARISTOTLE study, upper digestive hemorrhages accounted for 59% of digestive hemorrhages, compared to 41% of lower gastrointestinal tract, hemorrhoids, and rectum,9 similar figures to those of the ENGAGE-AF TIMI 48 study.10 A subanalysis of the ROCKET study showed the following distribution: 48% upper gastrointestinal tract and 52% lower gastrointestinal tract and rectum.11 Previous studies performed with VKA showed higher rates of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages, up to 75%,12 and thus treatment with proton pump inhibitors was recommended.

The fear of digestive hemorrhages in anticoagulated patients leads to a very generalized prescription of proton pump inhibitors. There is evidence supporting efficacy in prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients treated with anti-inflammatories, antiplatelets, and vitamin K antagonists,13 even of a change in the proportion of digestive hemorrhages, with reduction of the upper and a relative increase of those originated in the lower digestive tract.14 However, theoretically this measure would nor result in a reduction of low digestive hemorrhages, and they have been the most frequent in our study.

Intracranial bleedingUndoubtedly, intracranial bleeding is the most feared complication in patients anticoagulated. It is responsible for the greatest number of deaths and also for the majority of functional sequelae in anticoagulated patients.15 It is estimated that oral anticoagulation increases 2 to 5 fold the risk of presenting an intracranial hemorrhage,16 although these data probably reflect more the figures of vitamin K antagonists than those of direct-acting anticoagulants, since the latter have consistently shown a reduction in intracranial hemorrhage compared to warfarin,10,17–19 with figure more similar to those of simple antiplatelet therapy with aspirin.20

Although the severity of intracranial hemorrhage is evident in all studies, its frequency may be underestimated, especially in publications in which both major and minor hemorrhages are evaluated. The analysis of hemorrhages associated with hospitalizations yields the proportion of intracranial hemorrhages in relation to other relevant hemorrhages, removing from the denominator some minor bleeding episodes that are resolved in the emergency department or even in outpatient consultations. In our study, intracranial hemorrhages represented 30.6% of the total. The main randomized clinical trials show lower figures of intracranial hemorrhage compared to the rest of major hemorrhages, with values ranging from 8% to 25%.10,17–19 We attribute this difference to the patient selection bias inherent to clinical trials and to the comparison with major hemorrhages, a percentage of which may have been managed on an outpatient basis. In the comparison with other observational registers, we find values as different as 2%, 5% or 17%,21,22 in most cases figures lower than ours, differences that we also attribute to the fact that our results reflect the percentage against the total of bleedings causing hospitalization.

Mortality in bleeding admissionsIn our population, in-hospital mortality was 15.2%, a figure consistent with previous publications in anticoagulated patients. A recent retrospective series showed that mortality in patients treated with warfarin and admitted with excess of anticoagulation was 9.4%, although after excluding patients without bleeding, mortality among patients admitted with bleeding and anticoagulation with warfarin increased to 12%.23 The data published in the literature show considerable variability, probably reflecting differences in the selection of the study population. A meta-analysis of patients anticoagulated for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary thromboembolism showed a mortality of 13.4% after an episode of major hemorrhage.24 In the ATRIA study, which included patients anticoagulated for NVAF, a mortality of 23.5% was reported 30 days after admission for intracranial hemorrhage or major extracranial hemorrhage. In this study, 88% of deaths corresponded to intracranial hemorrhages, and the entire population was treated with warfarin.15 On the contrary, another study in patients anticoagulated with warfarin admitted for major hemorrhage or with hemorrhage during admission for another reason, in-hospital mortality was 4.9%, significantly lower.21

The mortality after a bleeding episode is high, not only for the risk directly attributed to the hemorrhage, but also to the frailty of patients who survive the acute phase of the major bleeding. An analysis performed in patients from the RE-LY and ACTIVE studies showed that a patient surviving an episode of intracranial hemorrhage had a 27-fold higher risk of mortality compared to patients with similar characteristics, and in nonfatal extracranial hemorrhages the excess of mortality in the follow-up increased 5 times.25 In a similar publication from the ARISTOTLE study, this increase was higher, with mortality 121 times higher in case of nonfatal intracranial hemorrhage and 12 times higher in the case of nonfatal extracranial hemorrhage.26

The increase in mortality observed in patients who survive a severe hemorrhage is due to a combination of factors. Hemorrhages appear in patients with greater frailty and the bleeding itself weakens the patient even more, especially when it causes neurological deficits or when it requires surgical interventions or prolonged hospitalizations. The almost constant withdrawal of anticoagulants and antiplatelets, which often are not restarted, is another key factor that conditions the prognosis. In a subanalysis of the ARISTOTLE study, a 12-fold increase in the risk of myocardial infarction or stroke was detected after suffering a major nonfatal hemorrhage, in addition to the increased risk of bleeding in patients who had already overcome a major hemorrhage.26 Other factors possibly involved in the high mortality of patients who survive bleeding are the adverse effects of transfusions, anemia, subclinical organ damage during acute hemorrhages, and the prothrombotic state that accompanies major hemorrhages.27

Mortality in patients anticoagulated for NVAF is mostly due to cardiac causes: myocardial infarction, heart failure, and sudden death, while mortality directly related to thrombotic and hemorrhagic episodes represents only 6%.28 The appearance of hemorrhagic phenomena is a predisposing factor for cardiac mortality. In the ENGAGE-AF TIMI 48 study, the low-dose randomized treatment arm of edoxaban is a clear example of the importance of bleeding prevention: despite a lower reduction in stroke compared with warfarin, a significant reduction in mortality was obtained because of the marked reduction of major hemorrhages.10

LimitationsWe must acknowledge some limitations. This study was observational and may be subject to confounding factors. Because of the nature of the study the diagnoses are drawn from the hospital-determined codes in the medical records, allowing the possibility of misclassification, and in some cases imprecision (unspecified digestive hemorrhages). Data were obtained from an information services company; the main limitation is that only a small number of variables were available. Much relevant information like the type of anticoagulant treatment, concomitant meditation and type and severity of comorbidities was not available. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision is not the current diagnostic tool recommended, as has been replaced by the Tenth Revision.

ConclusionsHemorrhages in patients anticoagulated for NVAF have a high sanitary impact. The most frequent hemorrhages were digestive only a third of them were localized as upper, followed closely by cerebral hemorrhages. Hospital mortality in this group of patients was high.

FundingThis work has received an unrestricted educational grant from CIBER CV 16/11/00420, 16/11/00226, Alianza Pfizer-BMS.

Conflicts of interestJ. Chaves is an employee of the company Pfizer. The rest of the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

- -

Chronic oral anticoagulation is the cornerstone for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, but it carries a load of bleeding episodes.

- -

The most frequent hemorrhages that lead to hospitalization are digestive, interestingly only a third of them were localized as high.

- -

In-hospital mortality in this population is high.