The sliding between internal and external segments of the myocardium assumes opposite directions in their movements, during the systolic and suction phases of the heart, generating friction. Our objective was to considerer the possibility of the existence of a lubricant that prevents friction wear in myocardial torsion and detorsion movements.

MethodsTwenty-four hearts were used: (a) Fifteen two-year-old bovine hearts weighing 800–1000g. (b) 9 human hearts (two 16- and 23-week gestation embryos, one from a 10-year-old child weighing 250g and 6 from adults, with an average weight of 300g). In the hearts 5 transverse, 2cm thick sections were made from base to apex to analyze the hyaluronic acid. All samples were subjected to histochemical analysis with Alcian blue staining, a reliable marker to identify the presence of hyaluronic acid, as an antifriction mechanism and even to provide a semi-quantitative assessment.

ResultsIn all the hearts analyzed, hyaluronic acid was found in the cleavage planes between the myocardial bundles. Histological and histochemical studies of the myocardium and its ducts (Thebesian and Langer) have shown that hyaluronic acid could be considered the antifriction effect, which flows throughout the myocardial thickness.

ConclusionsThis process involves opposite directions of the muscle segments and of these against the septal area. Sliding between these segments assumes opposite courses during the phases of the cardiac cycle (systole and suction) generating friction. In order to carry out this work, there is an antifriction lubricating mechanism represented by the venous Thebesian and Langer ducts together with the presence of hyaluronic acid. It is understandable that the fascicles of the myocardium, one on top on the other but in discordant directions, implies that the friction between them without a lubricating mechanism would be a decrease in the capacity of movement due to friction.

El deslizamiento entre los segmentos interno y externo del miocardio asume direcciones opuestas en sus movimientos, durante las fases sistólica y de succión del corazón, generando fricción. Nuestro objetivo fue considerar la posibilidad de la existencia de un lubricante que evite el desgaste por fricción en los movimientos de torsión y detorsión miocárdica.

MétodosSe utilizaron 24 corazones: (a) 15 corazones bovinos de 2 años con un peso de 800-1.000g; (b) 9 corazones humanos (2 embriones de 16 y 23 semanas de gestación, uno de un niño de 10 años y 250g de peso y 6 de adulto, con un peso medio de 300g). En los corazones se realizaron 5 cortes transversales de 2cm de espesor desde la base hasta el ápice para analizar el ácido hialurónico. Se realizó análisis histoquímico a todas las muestras con tinción de azul alcián, un marcador confiable para identificar la presencia de ácido hialurónico, como mecanismo antifricción e incluso para brindar una evaluación semicuantitativa.

ResultadosEn todos los corazones analizados se encontró ácido hialurónico en los planos de clivaje entre los haces miocárdicos. Los estudios histológicos e histoquímicos del miocardio y sus conductos (Thebesian y Langer) han demostrado que el ácido hialurónico, que fluye por todo el espesor miocárdico, se podría considerar como el efecto antifricción.

ConclusionesEste proceso involucra direcciones opuestas de los segmentos musculares y de estos contra el área septal. El deslizamiento entre estos segmentos asume rumbos opuestos durante las fases del ciclo cardiaco (sístole y succión) y genera fricción. Para llevar a cabo esta labor, existe un mecanismo lubricante antifricción representado por los conductos venosos de Tebesio y Langer junto con la presencia de ácido hialurónico. Es comprensible que los fascículos del miocardio, uno encima del otro, pero en direcciones opuestas, implica que la fricción entre ellos sin un mecanismo lubricante disminuiría la capacidad de movimiento debido a dicha fricción.

The myocardium internal and external segments sliding motion assumes opposite directions during the systolic and suction cardiac phases, generating friction. It is possible to understand from the laws of physics that friction between the segments implies a resistance to motion (Fig. 1).1–3

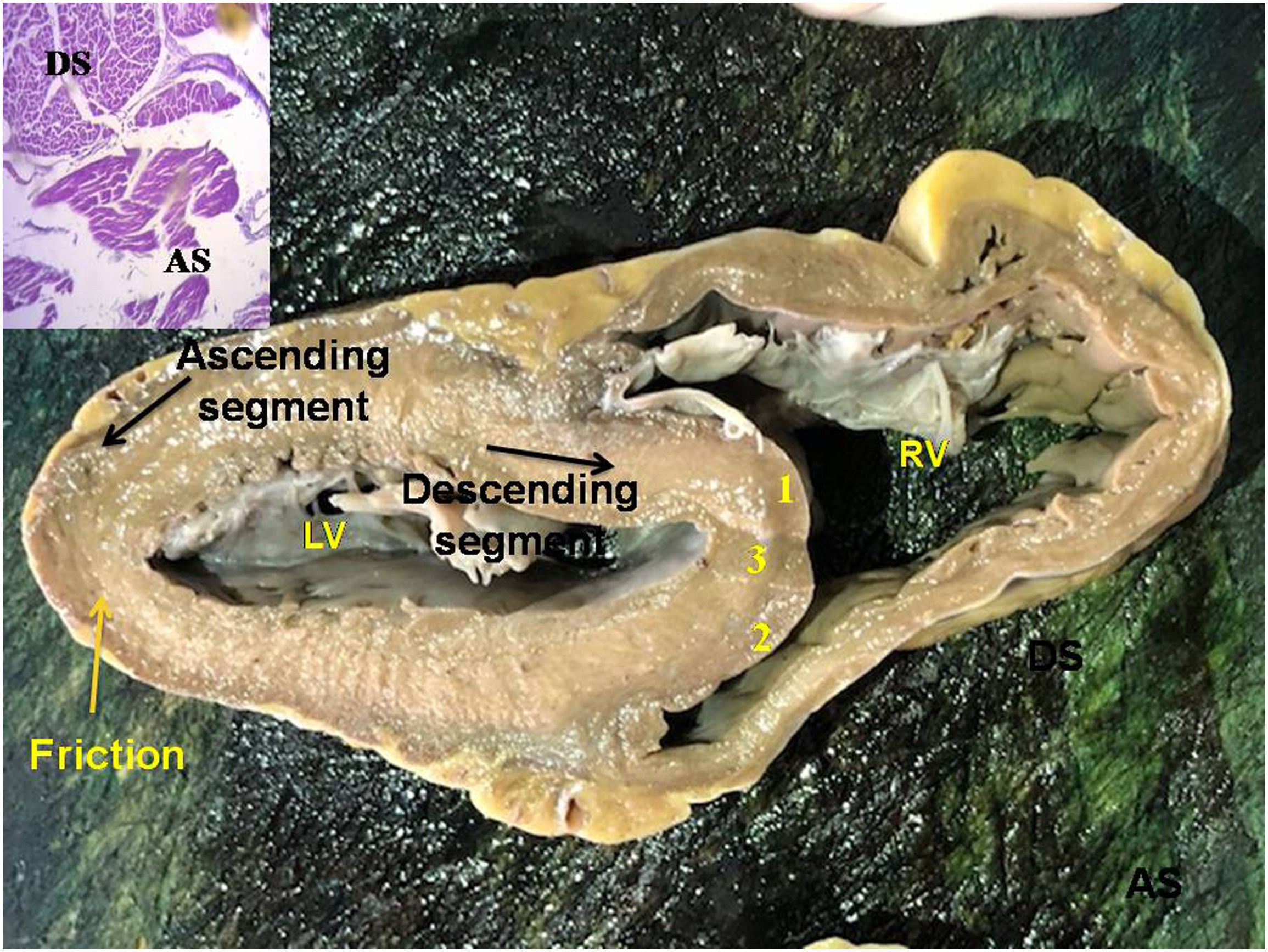

Transverse section of the left and right ventricles (human heart). The black arrows indicate the direction of motion of each segment during systole. The yellow arrow indicates the plane of friction between both segments. Anterior septal band (1); posterior septal band (2); intraseptal band (3). The histology in the inset shows the different orientation of the longitudinal fibers (ascending segment) in relation to the transverse fibers (descending segment). LV: left ventricle; RV: right ventricle.

This sliding motion between the myocardial segments during ventricular torsion–detorsion, situation verified by the speckle tracking technique that echocardiography has developed,4 implies that there must be an anti-friction mechanism to avoid the dissipation of the energy employed by the heart. Is there a specific histological explanation for this fact? Do Thebesian and Langer venous conduits play a role in this mechanism? Our objective was to considerer the possibility of the existence of a lubricant that prevents friction wear in myocardial torsion and detorsion movements.

MethodsIn this research, fresh bovine and human hearts have been used. The hearts examined correspond to material from morgue (human) and slaughterhouse (bovine). The study previously approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of President Perón Hospital. Twenty-four hearts were used: (a) Fifteen two-year-old bovine hearts weighing 800–1000g. (b) Nine human hearts (two 16- and 23-week gestation embryos, one from a 10-year-old child weighing 250g and six from adults, with an average weight of 300g).

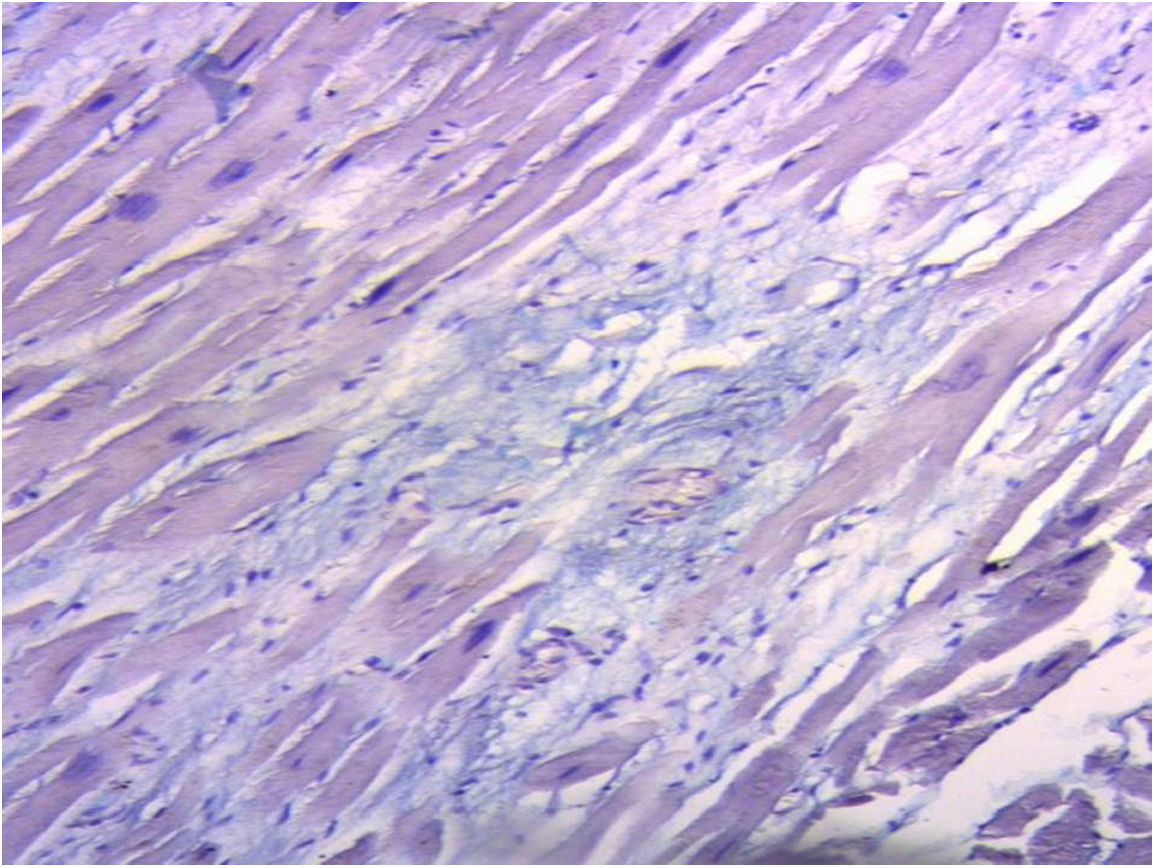

In the hearts five transverse, 2cm thick sections were made from base to apex to analyze the hyaluronic acid. All samples were subjected to histochemical analysis with Alcian blue staining, a reliable marker to identify the presence of hyaluronic acid, as an antifriction mechanism and even to provide a semi-quantitative assessment.

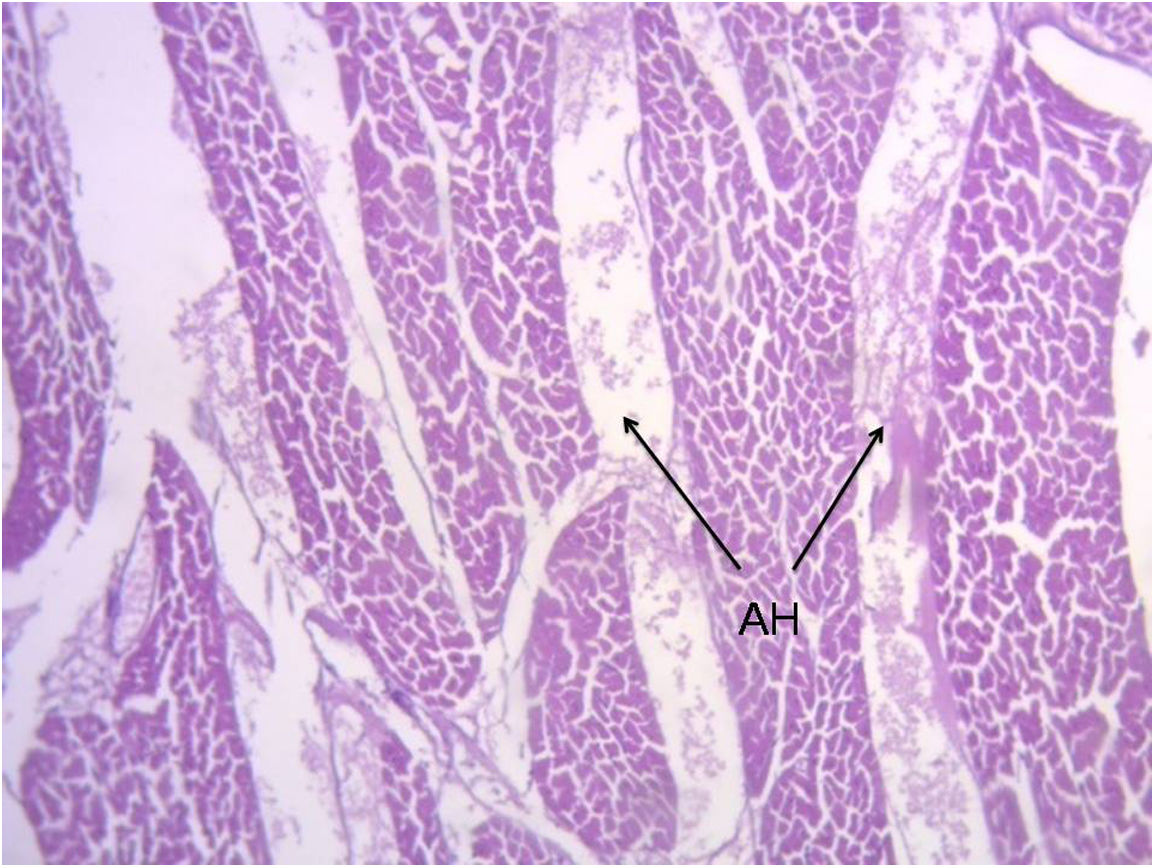

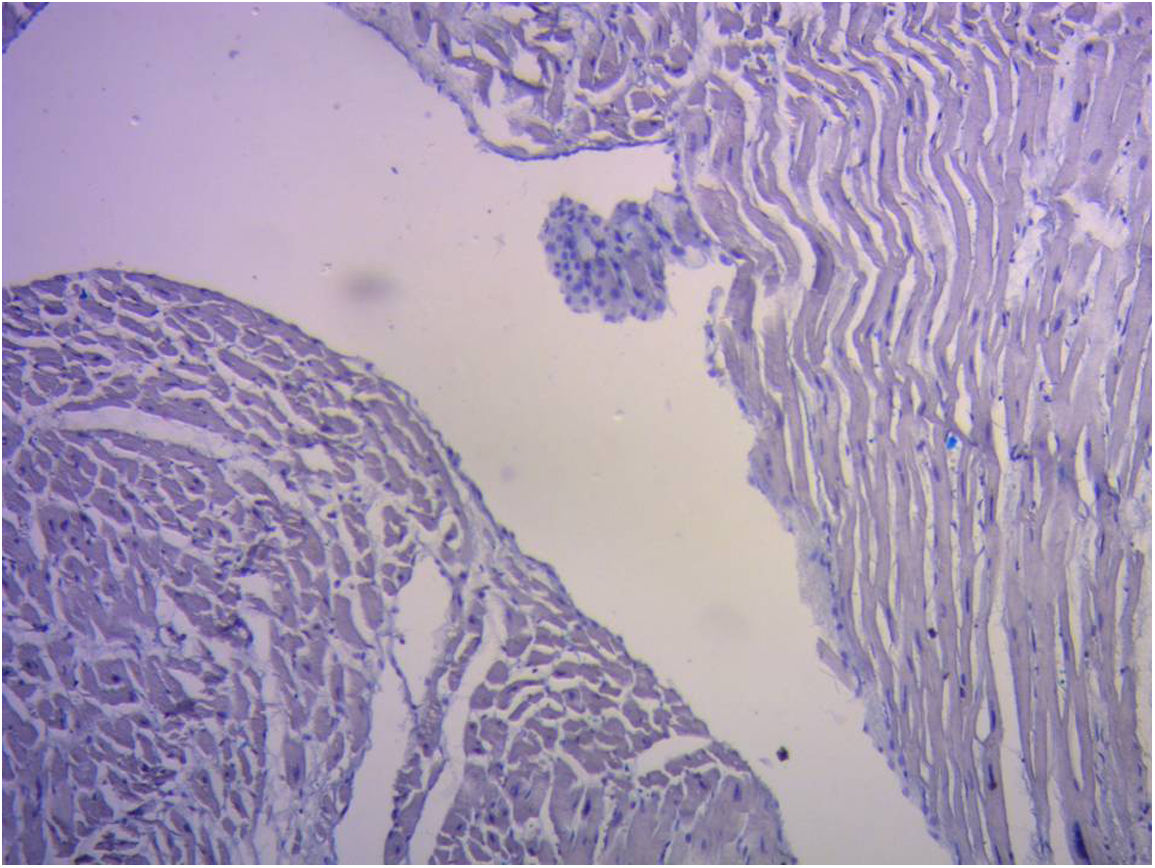

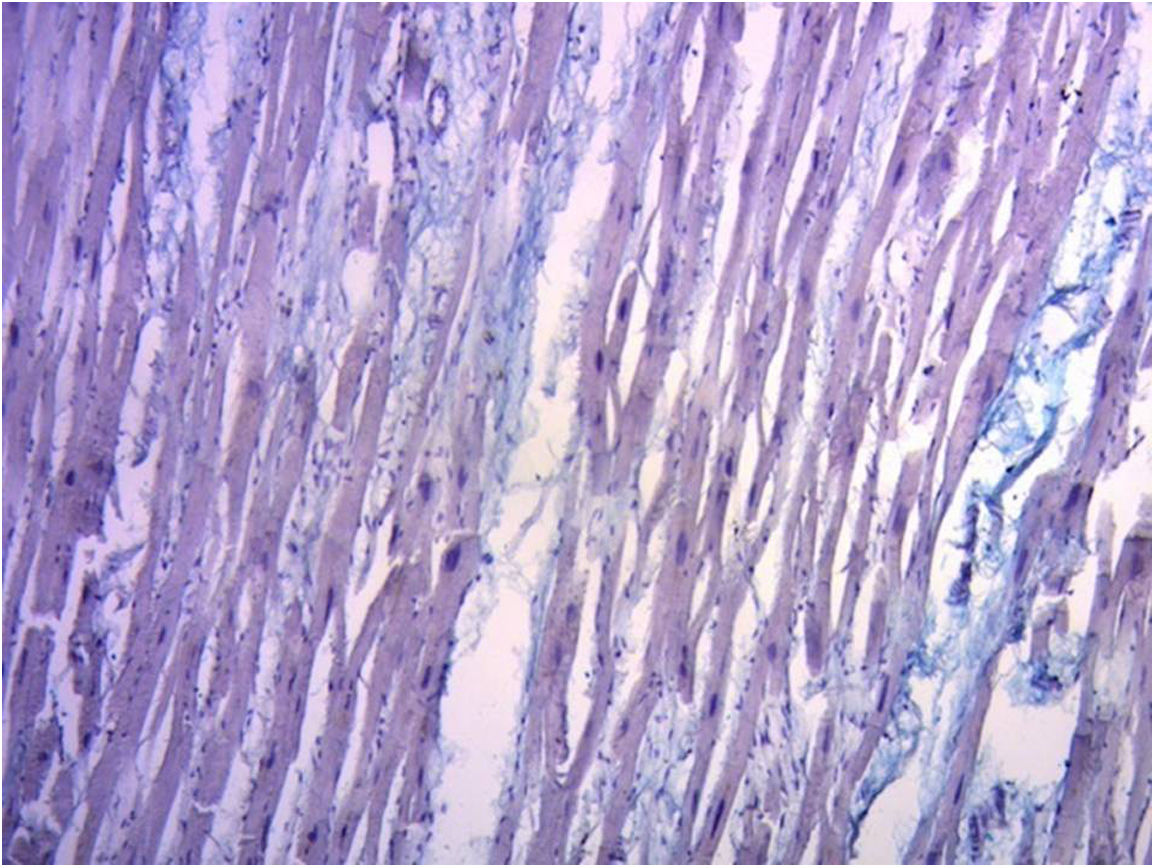

ResultsIn all the hearts investigated we found hyaluronic acid in the cleavage planes between the myocardial bundles associated to Thebesian and Langer venous conduits. These small venous conduits, which originate from intramyocardial veins (Thebesian) or from branching vessels of the great coronary vein (Langer), run across the myocardium and drain into the cardiac cavities (Fig. 2). The descending segment fibers in the anterior wall of the left ventricle course deeply in the mesocardium crossing obliquely and inner to those of the ascending segment located externally. Between both segments is the friction plane. In addition, among the cardiomyocytes, we have found spaces with a capillary network and plasmatic fluid rich in hyaluronic acid, stained with Alcian blue. In our study, hyaluronic acid was very scarce in the trigones, aorta and pulmonary artery, but very abundant in the myocardium and papillary muscles. No differences were found between bovine and human hearts (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, and Fig. 5).

It is understandable that the fascicles of the myocardium, one on top on the other but in discordant directions, implies that the friction between them without a lubricating mechanism would be a decrease in the capacity of movement due to friction.

DiscussionVentricular torsion represents the functional need that makes the heart fibers adopt an 8-shaped configuration.5,6 This is manifested as a deformation of the three myocardial axes: longitudinal, circumferential and radial, depending on the helical fiber orientation. The study of this rotation is a potential marker of myocardial disease severity when its twists deviate from normal values.

During systole, the three cardiac axes contract twisting the muscle mass which is “wrung as a towel” to achieve its ejective activity. To analyze this action, it has been essential to understand the course followed by the stimulus in the continuous myocardium, which explains cardiac motions.5 In the suction phase, during the first 100ms of diastole, the longitudinal axis lengthens and then with ventricular filling it expands and untwists, increasing its circumferential and radial axes. The helical myocardial anatomy, ventricular torsion, friction, and intraventricular ejective blood vortex correlate in the sequential explanation of cardiac dynamics.

Intramyocardial slidingThis arrangement is well seen in the modeling carried out in our investigation and in the dissection of the left ventricular wall where the descending segment is inner (endocardial) to the ascending segment (epicardial). The investigation performed with a longitudinal section of the left ventricle shows that both segments cross obliquely (Fig. 1). At the superior end of its trajectory, the ascending segment runs isolated to attach to the cardiac fulcrum.

During our studies, we considered that the antifriction mechanism could be generated by the loose “spongy” myocardial content with transmural blood currents (sinusoids), rudiments of the evolutionary and embryonic heart, in which Adam Thebesius’ veins (German anatomist, 1686–1732) and those described by Karl Langer (Vienna, 1819–1887) would play a fundamental role (hydraulic system). These coronary-ventricular connections, also studied by Vieussenius (1715), Minot (1900), Lewis (1904), Grant (1926), and Wearn (1928), would reduce the shearing stress between the muscle surfaces in the ventricular torsion–detorsion motions.7

These small venous conduits originate from intramyocardial veins (Thebesian) or from branching vessels of the major coronary vein (Langer), run across the myocardium and drain into the cardiac chambers. Obviously, the ones that drain into the left ventricular chamber deoxygenate the oxygenated blood coming from the lungs. In fact, this results in greater oxygen content in the left atrium than in the corresponding ventricle. Some essential questions arise here: Why would these venous conduits play a counterproductive function for the organism by deoxygenating arterial blood? What is their true role? Initial studies on these conduits considered that they could oxygenate the myocardium in case of coronary artery occlusion.

Hyaluronic acid, which appeared in the first chordate animals, is abundant in connective tissues.8 Half of hyaluronic acid is found in the skin and 25% in bones and joints. Due to its capacity to bind water it is an excellent lubricant and provides great resistance to mechanical pressures.9 Hyaluronic acid helps create the fabric of the extracellular matrix through its interactions with proteoglycans or collagen. When it is very concentrated it may interact with itself creating networks or meshes that bestow viscoelastic properties to tissues. During development it helps the morphogenesis of embryonic structures. For example, it may be released from basal epithelial layers, curving their shape due to the great amount of water it attracts.10

This functional association between the Thebesian and Langer venous conduits and the substantial amount of hyaluronic acid found in our investigations in bovine and human hearts, added to its lubricating role in the rest of the body, could be crucial to understand cardiac dynamics. Thus, ventricular torsion is correlated with a mechanism that facilitates myocardial segment sliding to avoid energy loss. These venous conduits and the helical contraction would therefore continuously drive the plasmatic fluid with hyaluronic acid through a rich capillary network. In our investigation, we have found between the cardiomyocytes, spaces with a capillary network containing a plasmatic fluid rich in hyaluronic acid.

In this regard, our findings of the presence of hyaluronic acid in the lacunar structure between the myocardial bundles in bovine and human hearts, together with Thebesian and Langer venous conduits as branches for the necessary hydration of this element, could clarify this lubricating effect, counteracting the abrasion between surfaces 100 as an antifriction mechanism. In fact, between the different segments there is no specific sliding membrane, but rather friction surfaces intersected by a spongy system that covers the entire myocardium and where hyaluronic acid with its lubricating capacity facilitates the sliding motion between them.11

LimitationsOwing to the importance of this finding it is necessary to confirm it with further investigations and other markers of hyaluronic acid.

ConclusionsWe know that the helical structure of the myocardial band allows the dynamic performance of ventricular twisting and untwisting. Anatomical studies, the progress of ventricular dynamic knowledge through the propagation of the electric impulse and echocardiographic studies of ventricular rotation confirm the structure-function relationship of the heart. Sliding between the internal and external myocardial segments takes opposite directions during the ejective and suctions phases of the heart, generating friction. Energy expenditure would be great in the absence of a spongy system in the myocardium, consisting of Thebesian and Langer venous conduits with a lubricating antifriction system.

Histological and histochemical studies of the myocardium and its ducts (Thebesian and Langer) have shown that hyaluronic acid could be considered the antifriction effect, wich flows throughout the myocardial thickness.

There is no knowledge about hyaluronic acid in the heart. The study of cardiac mechanics and friction between its segments led us to this finding.

Does it contribute anything new?Sliding between the internal and external myocardial segments takes opposite directions during the ejective and suctions phases of the heart, generating friction. Energy expenditure would be great in the absence of a spongy system in the myocardium, consisting of Thebesian and Langer venous conduits with a lubricating antifriction system. Histological and histochemical studies of the myocardium and its ducts (Thebesian and Langer) have shown that hyaluronic acid could be considered the antifriction effect, which flows throughout the myocardial thickness.

None declared.

Authors’ contributionsJ. Trainini: Research Coordination; M. Beraudo: Anatomy; M. Wernicke: Histology; F. Carreras Costa: Histology; A. Trainini: Anatomy; V. Mora Llabata: Cardiac mechanic; J. Valle Cabezas: Cardiac mechanic; D. Lowenstein Haber: Images; M.E. Bastarrica: Anatomy; J. Lowenstein: Images.

Conflicts of interestThis research has no conflicts of interest. J. Lowenstein is subsidized by General Electric, for other work that is not related to this research.