Same-day discharge (SDD) can be considered for patients who traditionally required overnight stay (ONS) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The authors aimed to evaluate viability of SDD-PCI.

MethodsRetrospective single-center observational study of patients who underwent elective PCI. SDD patients were selected based on clinical, angiographic, and sociodemographic characteristics. Patient and procedure characteristics were collected from local databases, and SDD-PCI adverse events (all-cause mortality, acute coronary syndrome, stent thrombosis, reintervention, major bleeding, stroke, contrast-induced renal failure, vascular access complications) at 30-days were analyzed.

ResultsThis study included 147 patients, 76% males with a mean age of 66±10, that underwent elective PCI during the first year after implementation of SDD protocol. Most patients undergoing elective PCI were discharged the same day (n=94, 64%). ONS group, when compared to SDD, had higher rates of acute coronary syndrome (38% vs 19%, P=.01) and left ventricular dysfunction (17% vs 6%, P=.04), higher Syntax I score (10 points [6–16] vs 8 points [5–12]; P=.01), more cases of multivessel PCI (24% vs 6%, P<.01) and a surrogate for longer procedures – fluoroscopy time (11min [7–15] vs 8min [5–13]; P=.02). There were no adverse events during the 30-day follow-up period of the patients treated in ambulatory regimen.

ConclusionsSDD-PCI is a safe procedure. Protocol implementation is key to guide interventional cardiologists in low-risk patient selection. The potential role in decreasing bed-shortage, hospital overcrowding, and healthcare costs is pivotal.

Se puede considerar el alta en el mismo día (SDD) para un número significativo de pacientes que, de otro modo, habrían requerido pasar la noche (ONS) tras someterse a un intervencionismo coronario percutáneo (ICP). El objetivo de los autores fue evaluar la viabilidad del SDD-ICP.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo unicéntrico de pacientes con síndrome coronario crónico sometidos a ICP electiva. Los pacientes candidatos a SDD se definieron de acuerdo con las características clínicas, angiográficas y sociodemográficas. La información clínica de los pacientes y los datos relacionados con el procedimiento se recogieron de las bases de datos locales. Se analizaron los eventos adversos de la SDD-ICP (mortalidad por todas las causas, síndrome coronario agudo, trombosis del stent, reintervención, hemorragia mayor, accidente cerebrovascular, insuficiencia renal inducida por contraste, complicaciones del acceso vascular) a los 30 días.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 147 pacientes, 76% varones con una edad media de 66±10 años, que se sometieron a ICP electiva durante el primer año tras la implementación del protocolo SDD. La mayoría de los pacientes sometidos a ICP electiva en el centro fueron dados de alta el mismo día (n=94, 64%). En el grupo ONS, en comparación con el grupo SDD, el antecedente de síndrome coronario agudo fue más frecuente en (38% frente a 19%, p=0.01), al igual que la disfunción ventricular izquierda (17% frente al 6%, p=0,04). Los pacientes ingresados tras ICP electiva presentaron mayor puntuación en el Syntax score I (10 puntos [6-16] vs 8 puntos [5-12]; p=0,01), se sometieron con mayor frecuencia a ICP multivaso (24% frente a 6%, p <0,01) y tuvieron un mayor tiempo de fluoroscopia, indicativo de procedimientos más largos (11min [7-15] vs 8min [5-13]; p=0,02) en comparación con SDD-PCI. No hubo eventos adversos durante el período de seguimiento de 30 días en los pacientes tratados en régimen ambulatorio.

ConclusionesEl SDD-ICP es un procedimiento seguro. La implementación de un protocolo es clave para guiar a los cardiólogos intervencionistas en la selección de pacientes de bajo riesgo. En un contexto de escasez de camas, sobrecarga hospitalaria y costes de la atención sanitaria puede ser esencial.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a broadly performed procedure worldwide. A significant proportion of cases is undertaken in an elective basis.1–3 Safety and efficacy of the procedure have been improved by advances in available devices and newer techniques. Drug eluting stents have become the standard of care, overcoming in safety and efficacy the older generation bare metal stents and balloon angioplasty.4–6 Moreover, the radial first strategy for access has permitted safer procedures with lower complications.7,8

In selected patients, same-day discharge after elective PCI (SDD-PCI) has become a possibility and several studies have demonstrated safety, feasibility, and patient preference.9–11 SDD-PCI represents an opportunity to reduce hospital stays, avoiding unnecessary nosocomial complications and to optimize bed allocation and costs.12,13 Nevertheless, the risk profile of patients undergoing PCI is changing, and procedures are more frequently performed in an aging population.1

Therefore, the authors aimed to evaluate safety and feasibility of elective outpatient PCI in low-risk selected patients upon implementation of institutional SDD-PCI protocol in real-world conditions.

MethodsStudy participantsThis retrospective observational single-center study collected data from all the consecutive patients with chronic coronary syndromes who underwent elective PCI from October 2019 to November 2020 (1-year) in Hospital de Braga.

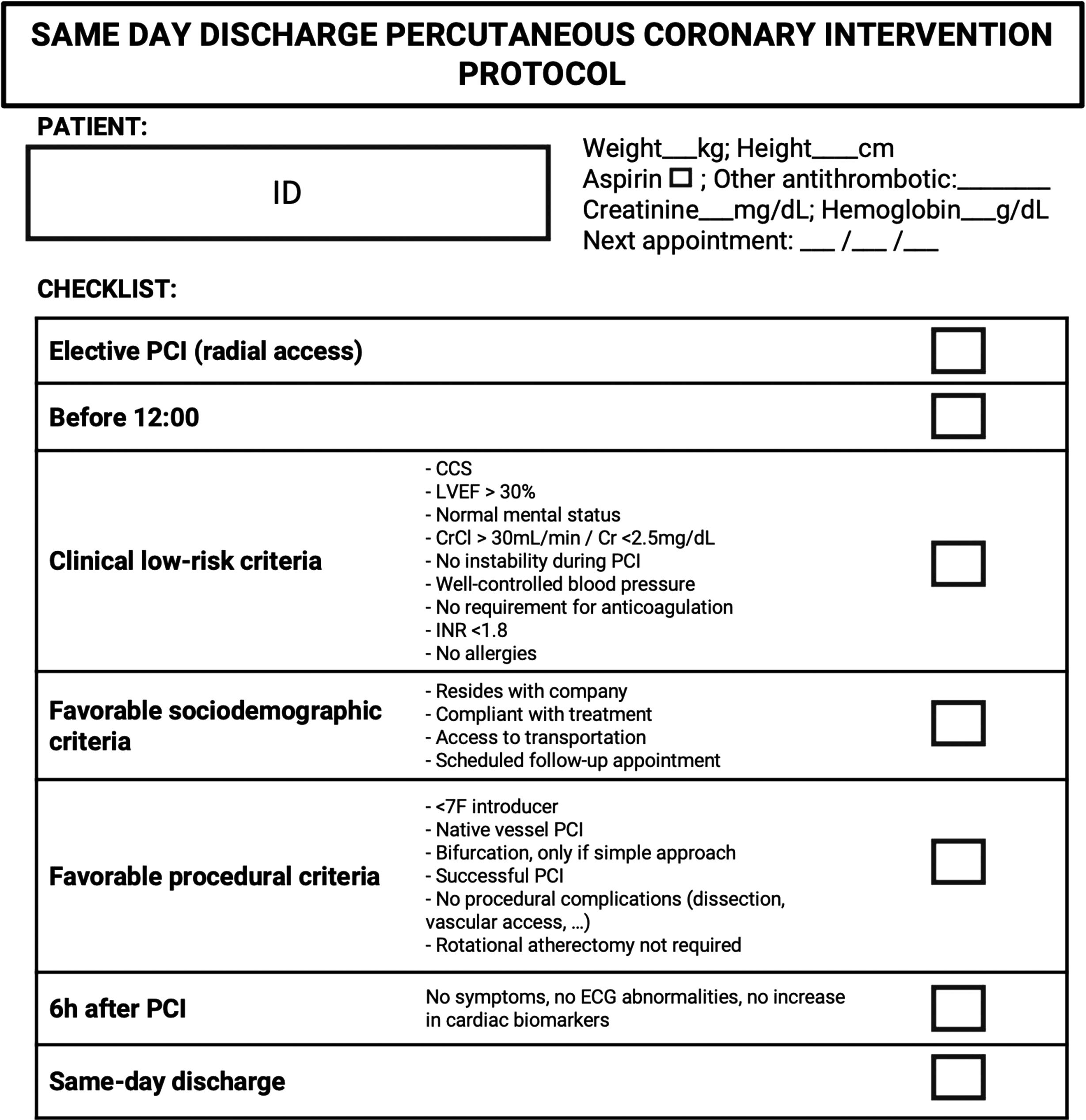

Protocol and post-procedure managementPatents who qualified SDD were defined by an approved institutional protocol that includes low risk clinical characteristics and favorable angiographic and sociodemographic criteria (Fig. 1).14 However, the interventional cardiologist could individualize management of the patient, based on professional knowledge and opinion.

Institutional protocol of outpatient elective percutaneous coronary intervention. CCS, chronic coronary syndrome; Cr, creatina; CrCl, creatine clearance; ECG, electrocardiogram; ID, identification; INR, international normalized ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Most patients undergoing PCI at our center stayed in a 4-bed recovery room immediately after the procedure and were afterwards transferred according to the stablished course: (a) day hospital room (3-bed plus sitting capacity) for SDD or (b) admitted in the ward for overnight stay (ONS).

Data collectionData was collected from the catheterization laboratory dedicated digital database and from patients’ medical records. Demographics and clinical characteristics were assessed. Procedural, peri-procedural and 30-day follow-up data was also collected.

Clinical endpointsPrimary endpoint was a composite of adverse events (all-cause mortality, acute coronary syndrome, stent thrombosis, re-intervention, major bleeding, stroke, contrast-induced renal failure, vascular access complications) at 30 days.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics included means (± standard deviation) or median [interquartile range] for continuous variables and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables.

Continuous variables were compared with independent samples Student t test for parametric variables, or Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric distribution. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

Statistical significance was established at a P<.05 for all tests. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 25).

Confidentiality and ethical considerationsAll patients gave informed consent for the procedure executed. Confidentiality and anonymity of all collected data were ensured during all phases of the study. This study was approved by the local ethics committee and comply with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration.

Reporting of dataThe manuscript has been submitted following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) recommendations.

ResultsBaseline characteristicsThis study included 147 patients, 76% males with a mean age of 66±10, that underwent elective PCI during the first year after implementation of SDD protocol. Most patients undergoing elective PCI in the center were discharged in the same day (n=94, 64%).

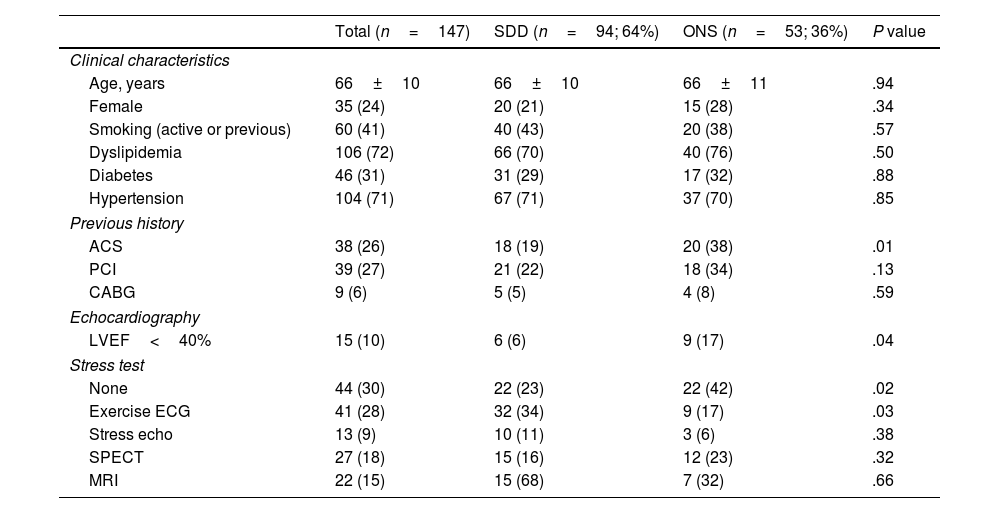

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients submitted to elective PCI and the comparison between SDD and ONS. Clinical characteristics such as age, sex and risk factors were balanced between the 2 groups. Previous history of acute coronary syndrome was more frequent in ONS when compared to SDD (38% vs 19%, P=.01). Left ventricular dysfunction (<40%) was more frequent in ONS patients (17% vs 6%, P=.04). Lastly, SDD patients were more often submitted to a stress test before elective PCI when compared to ONS (77% vs 58%, P=.02), mostly due to a significantly higher percentage of exercise electrocardiogram in this group (34% vs 17%, P=.03).

Baseline characteristics.

| Total (n=147) | SDD (n=94; 64%) | ONS (n=53; 36%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 66±10 | 66±10 | 66±11 | .94 |

| Female | 35 (24) | 20 (21) | 15 (28) | .34 |

| Smoking (active or previous) | 60 (41) | 40 (43) | 20 (38) | .57 |

| Dyslipidemia | 106 (72) | 66 (70) | 40 (76) | .50 |

| Diabetes | 46 (31) | 31 (29) | 17 (32) | .88 |

| Hypertension | 104 (71) | 67 (71) | 37 (70) | .85 |

| Previous history | ||||

| ACS | 38 (26) | 18 (19) | 20 (38) | .01 |

| PCI | 39 (27) | 21 (22) | 18 (34) | .13 |

| CABG | 9 (6) | 5 (5) | 4 (8) | .59 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF<40% | 15 (10) | 6 (6) | 9 (17) | .04 |

| Stress test | ||||

| None | 44 (30) | 22 (23) | 22 (42) | .02 |

| Exercise ECG | 41 (28) | 32 (34) | 9 (17) | .03 |

| Stress echo | 13 (9) | 10 (11) | 3 (6) | .38 |

| SPECT | 27 (18) | 15 (16) | 12 (23) | .32 |

| MRI | 22 (15) | 15 (68) | 7 (32) | .66 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; ECG, electrocardiogram; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ONS, overnight stay; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SPECT, single-photon emission computerized tomography; SDD, same-day discharge.

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean±standard deviation.

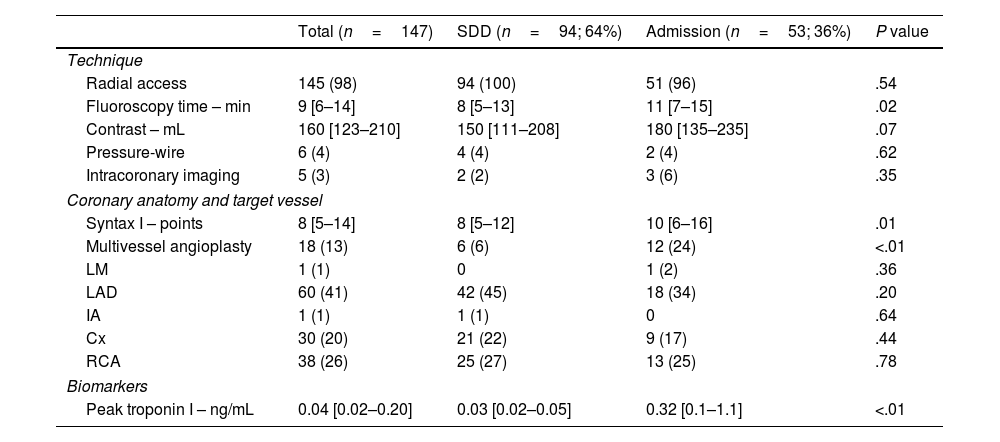

Table 2 presents the procedural characteristics of patients submitted to elective PCI. The percentage of radial access did not differ between groups, with high percentages of radial access in the population analyzed (SDD-PCI: 100% vs ONS: 98%, P=.54). Patients admitted after elective PCI had higher Syntax I score (10 points [6–16] vs 8 points [5–12]; P=.01), were more frequently submitted to multivessel PCI (24% vs 6%, P<.01), had a higher surrogate for longer procedures – fluoroscopy time (11min [7–15] vs 8min [5–13]; P=.02) and higher post-procedural troponin I measurements (0.32ng/mL [0.1–1.1] vs 0.03ng/mL [0.02–0.05]; P<.01) when compared to SDD-PCI. Contrast volume, use of pressure wires and intracoronary imaging did not differ between groups.

Procedural characteristics.

| Total (n=147) | SDD (n=94; 64%) | Admission (n=53; 36%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | ||||

| Radial access | 145 (98) | 94 (100) | 51 (96) | .54 |

| Fluoroscopy time – min | 9 [6–14] | 8 [5–13] | 11 [7–15] | .02 |

| Contrast – mL | 160 [123–210] | 150 [111–208] | 180 [135–235] | .07 |

| Pressure-wire | 6 (4) | 4 (4) | 2 (4) | .62 |

| Intracoronary imaging | 5 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (6) | .35 |

| Coronary anatomy and target vessel | ||||

| Syntax I – points | 8 [5–14] | 8 [5–12] | 10 [6–16] | .01 |

| Multivessel angioplasty | 18 (13) | 6 (6) | 12 (24) | <.01 |

| LM | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) | .36 |

| LAD | 60 (41) | 42 (45) | 18 (34) | .20 |

| IA | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | .64 |

| Cx | 30 (20) | 21 (22) | 9 (17) | .44 |

| RCA | 38 (26) | 25 (27) | 13 (25) | .78 |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| Peak troponin I – ng/mL | 0.04 [0.02–0.20] | 0.03 [0.02–0.05] | 0.32 [0.1–1.1] | <.01 |

Cx, circumflex artery; IA, intermediate artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LM, left main artery; RCA, right coronary artery; SDD, same-day discharge.

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

Target vessel differences in single-vessel angioplasties were not detected (Table 2). A minority of patients was submitted to procedures on chronic total occlusion, and all were admitted for ONS (n=3; 2%). Only 2 patients (1%) had intervention on in-stent restenosis and were both admitted in the ward. Bifurcation lesions were well-balanced between ONS and SDD patients (41% vs 60%, P=.60), all treated with 1 stent technique. Unsuccessful procedures were rare and occurred exclusively in the ONS group (n=4; 8%). Among the patients, 5 (3%) experienced small dissections and were therefore admitted for surveillance.

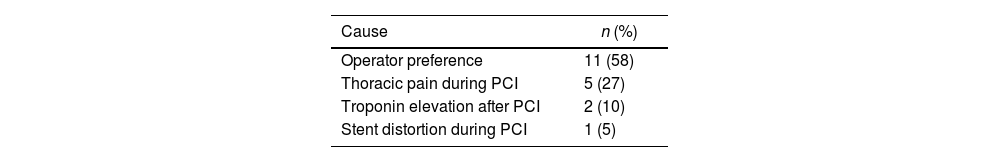

Discharge timingAmbulatory patients were discharged after a mean surveillance period of 290±54min. Out of 113 patients meeting protocol criteria (76% eligibility), only 93 (64%) were discharged on the same day. Table 3 outlines reasons for ONS in this group of patients, with main causes being operator preference (56%, n=11) and thoracic pain during the procedure (27%, n=5).

Clinical endpointsThere were no adverse events (mortality, acute coronary syndrome, stent thrombosis, re-intervention, major bleeding, stroke, contrast-induced renal failure, vascular access complications) during the 30-day follow-up period in the SDD regimen.

DiscussionThis study provides compelling evidence for the safety of implementing SDD-PCI in a high-volume PCI center. Notably, all patients who underwent SDD-PCI during the inaugural year of the program experienced a complication-free 30-day post-procedure period. These findings align with existing studies that have similarly demonstrated the safety of SDD-PCI procedures.15–18 However, it is worth noting that none of these prior studies specifically delved into the safety of implementing such a program.

In an era characterized by a shortage of hospital beds, further underscored by the healthcare strain imposed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the reduction of unnecessary admissions has become a paramount objective in optimizing healthcare services.

While European guidance on post-PCI discharge timing is still lacking, the implemented protocol aligns closely with the most recent recommendations from relevant medical societies.19,20 The observed discharge timing was around 5h, noticeably shorter than the proposed 6-h surveillance period. This could be explained by the interventional cardiologist's self-reliance in the selection of low-risk patients and uneventful procedures for SDD, which is key to mitigate adverse events. Our observations emphasize that ONS is often reserved for higher risk patients (i.e. history of previous acute coronary syndrome and cardiac dysfunction) and procedures of greater complexity (i.e. higher Syntax scores, multivessel PCI and longer procedures). Similarly, patients with chronic total occlusion lesions and in-stent restenosis were also allocated to ONS. It is noteworthy, however, that guideline-directed strategies should not be neglected in the context of SDD patients, as evidenced by the consistent use of pressure wires and intracoronary imaging, which did not significantly differ between the 2 regimens. Furthermore, although infrequent in the analyzed cohort, hospital admission following unsuccessful or complicated PCI was well-defined in the protocol.

Additionally, the absence of adverse events can be partly attributed to the exclusive use of radial access, which is recommended as the preferred approach when considering SDD-PCI.21 Our strategy also involved a recommended post-procedure stay of 6h. Importantly, most complications after elective PCI tend to manifest during and within the first 3h following the procedure, becoming exceedingly rare beyond the 6-h mark.22

Despite the mounting evidence supporting the safety of SDD-PCI, its widespread adoption in uncomplicated PCI cases remains limited.23 Significantly, protocol adherence in this study was consistently high from the initial implementation phase throughout the entire first year. This high level of compliance, coupled with most elective PCI cases being managed on an ambulatory basis, contributed significantly to the program's successful implementation. Furthermore, it's important to highlight that outpatient procedures are generally more comfortable for patients and their families.11

It is worth noting that this protocol enabled us to sustain elective activity in the cath lab during the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the numerous associated restrictions. Remarkably, it did not have a significant impact on our activity levels, apart from the expected reduction in hospital admissions, which was partly due to patients’ reluctance to seek healthcare services during the pandemic. This protocol allowed us to carry out elective angioplasties, which might not have been possible during the most critical weeks of the COVID-19 crisis if patients were required to stay in the hospital.

Study limitationsFirst, this non-randomized observational single-center study analyzing a singular protocol for SDD-PCI. Therefore, a highlighted limitation is the study's low sample size, exacerbated by a lower total number of angioplasties performed during the COVID-19 pandemic period compared to previous years.

Furthermore, the absence of events in the early discharge group was excepted due to exclusion criteria in this group and to the possibility of interventional cardiologists to vary the group assignment based on post-angioplasty evolution. Additionally, the fluoroscopy time and Syntax score are very low, indicating procedures of low complexity and, therefore, a specific selection of candidates. This may impact the external validity of the study.

Moreover, we solely present the follow-up data for SDD-PCI patients, as the comparison with ONS is unviable, given that these groups are intrinsically different and again reflect the selection of lower risk patients for SDD and higher risk patients for ONS.

Lastly, it is important to note that the implementation of the protocol coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially impacting strategy selection based on available hospital bed capacity.

ConclusionsSDD-PCI is a safe and feasible procedure. Protocol implementation is key to guide interventional cardiologists in low-risk patient selection. The role in decreasing bed-shortage, hospital overcrowding, and optimizing healthcare costs is pivotal.

- -

SDD-PCI has become a possibility and several studies have demonstrated safety, feasibility, and patient preference.

- -

SDD-PCI represents an opportunity to reduce hospital stays, avoiding unnecessary nosocomial complications and to optimize bed allocation and costs.

- -

Implementation of SDD-PCI is safe and feasible.

- -

Protocol adherence is key to guide interventional cardiologists in low-risk patient selection.

- -

The role in decreasing bed-shortage, hospital overcrowding, and optimizing healthcare costs is pivotal. The presented protocol allowed us to carry out elective angioplasties, which might not have been possible during the most critical weeks of the COVID-19 crisis.

None.

Statement on the use of artificial intelligenceNo artificial intelligence tool has been used to write this article.

Ethical considerationsAll patients gave informed consent for the procedure executed. Confidentiality and anonymity of all collected data were ensured during all phases of the study. This study was approved by the local ethics committee and comply with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration. The manuscript has been submitted following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) recommendations.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have participated in the work and have reviewed and agree with the content of the article, none of the article contents are under consideration for publication in any other journal or have been published in any journal and the authors have no conflicting interests. The corresponding author guarantees that all authors meet each of the characteristics defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors in the criteria for authorship of scientific articles.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Abbreviations: COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; ONS: overnight stay; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SSD: same-day discharge.