This study aims to describe relationship between physical performance (PP) and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure (HF).

MethodsThis study used a cross-sectional design for data collection. Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) was used as a measurement tool, while the Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test (FTSST) was used to assess PP. The data were processed by Pearson correlation coefficient, t-test, one-way ANOVAs, and Hierarchical multiple regression.

ResultsA total of 180 patients with HF participated in this study, with the mean age of respondents being 59.98 (11.86) years old. Among these respondents, 60% were male, with a mean PP of 9.56 (6.94)s and a mean MLHFQ of 43.14 (20.74). The results showed that MLHFQ had a significant correlation with HF medication (r=.16, P<.05), health status (r=.24, P<.01), FTSST (r=.40, P<.01), and MLHFQ was significantly associated with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Classification (F=8.358, P<.001). There were three variables identified as predictors of MLHFQ, namely health status (β=−2.22), NYHA Class III (β=1.27), and FTSST (β=3.03), and were predicted to account for 31.1% of the variance in MLHFQ.

ConclusionsEfforts to increase PP from patients with HF can be an asset to improve health-related quality of life. Furthermore, health status and NYHA classifications are factors that can significantly affect health-related quality of life of patients with HF.

Este estudio tiene como objetivo describir la relación entre el rendimiento físico (RF) y la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca (IC).

MétodosSe utilizó un diseño transversal para la recolección de datos. Como herramienta de medición se empleó el cuestionario de MinnesotaLiving with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), mientras que la prueba Five Times Sit-to-stand (FTSST), para evaluar el RF. Los datos fueron procesados mediante coeficiente de correlación de Pearson, prueba t, ANOVA unidireccional y regresión múltiple jerárquica.

ResultadosUn total de 180 pacientes con IC participaron en este estudio. La edad media de los encuestados fue de 59,98 (11,86) años. Entre estos encuestados, 60% eran varones, con un RF medio de 9,56 (6,94) segundos y un MLHFQ medio de 43,14 (20,74). Los resultados mostraron que MLHFQ tenía una correlación significativa con la medicación HF (r = 0,16, p < 0,05), estado de salud (r = 0,24, p < 0,01), FTSST (r = 0,40, p < 0,01), y el MLHFQ se asoció significativamente con la clasificación de la New York Heart Association (NYHA) (F = 8,358, p < 0,001). Se identificaron tres variables como predictores de MLHFQ: estado de salud (β = -2,22), NYHA clase III (β = 1.27) y FTSST (β= 3.03), y se predijo que representarían 31,1% de la varianza en MLHFQ.

ConclusionesLos esfuerzos para aumentar la RF de los pacientes con IC pueden ser una ventaja para mejorar la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud. Además, las clasificaciones de estado de salud y NYHA son factores que pueden afectar significativamente la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud de los pacientes con IC.

Heart failure (HF) is one of the public health issues in the world that continuously increase every year, especially in adults in developing countries.1,2 The clinical manifestations of HF, such as dyspnea, fatigue, and shortness of breath, can affect several aspects of life both physically and psychosocially.3 Several studies have recognized that patients with HF tend to have decreased health-related quality of life (HRQOL).4,5

HRQOL is a complex concept that measures health of a person, including physical, spiritual, and psychosocial domains.4,6 A decrease in HRQOL has an impact on increasing re-hospitalization and mortality of patients with HF. Several studies have proven that HRQOL indicates health status (HS), disease severity, response to treatment, and disease progression in people living with HF.7,8 Despite receiving evidence-based treatment, patients with HF may not experience an improvement in their HRQOL, particularly those dealing with severe conditions.4 Therefore, the establishment of benchmarks is needed to improve HRQOL in people living with HF.

Physical performance (PP) is one of the benchmarks for improving several factors such as functional capacity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and exercise capacity of people living with HF,9,10 which contribute to HRQOL.11,12 Therefore, special attention for patients, families, and health workers is needed to increase PP from patients and enhance HRQOL for people living with HF.

MethodsStudy design and participantsA cross-sectional design was employed for analysis and consecutive sampling was carried out on 180 HF patients, consisting of both male (n: 108) and female (n: 72) at the outpatients unit. The respondents who agreed to participate were given informed consent. The respondents completed the data, including demographic characteristics, illness-related factors, the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), and they performed Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test (FTSST). This study has been reviewed and approved by the Hospital Institutional Review Board (HIRB) (PP04.03/XIX.3/3580/2021).

Study instrumentMLHFQ was used to measure HRQOL.13 Scores ranged from 0 to 105, with higher scores indicating lower HRQOL. MLHFQ used a Likert scale of 0–5, consisting of 21 items, and represented two dimensions, namely physical and emotional. Disease severity was assessed based on the New York Heart Association Classification (NYHA Class), which was a classification based on the level of physical activity associated with HF symptoms, the scale of the NYHA Class was I to IV, with higher classes indicating increased symptoms and decreased physical activity.14 However, only NYHA Classifications I–III were used in this study. HS was measured using the Self-Rated Health Subscale questionnaire. The Self-Rated Health Subscale consisted of four items, with scores ranging from 4 to 14, and higher scores indicated lower HS.15 The comorbidity status was measured using Charlson Comorbidity Index. The high score indicates the seriousness of the comorbidities.16

PP used the FTSST measuring instrument and the FTSST score was based on the amount of time (seconds) patients moved from sitting to standing and back to sitting five times. The lower the seconds to complete the test, the better the result.17 Furthermore, demographic characteristics consisted of age, gender, occupation, marital status, and place of residence. Disease-related factors included hemoglobin, body mass index, duration of HF diagnosis, comorbidity, and HF medications.

Statistical analysisBefore data analysis, all data were examined to check for errors, missing data values, distribution, normality of data on the main variables, homogeneity of variance, homoscedasticity, and linearity for each statistical procedure. Relationship between demographic characteristics, disease-related factors, PP, and HRQOL was explored using an independent t-test, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson correlation. Meanwhile, hierarchical multiple regressions explained the predictor variables on HRQOL. Dummy variables were performed on NYHA Classification and PP of the respondents in this study. Variables included in the regression model were those that were significant with HRQOL, based on a cut point value of P<.20 with HRQOL.

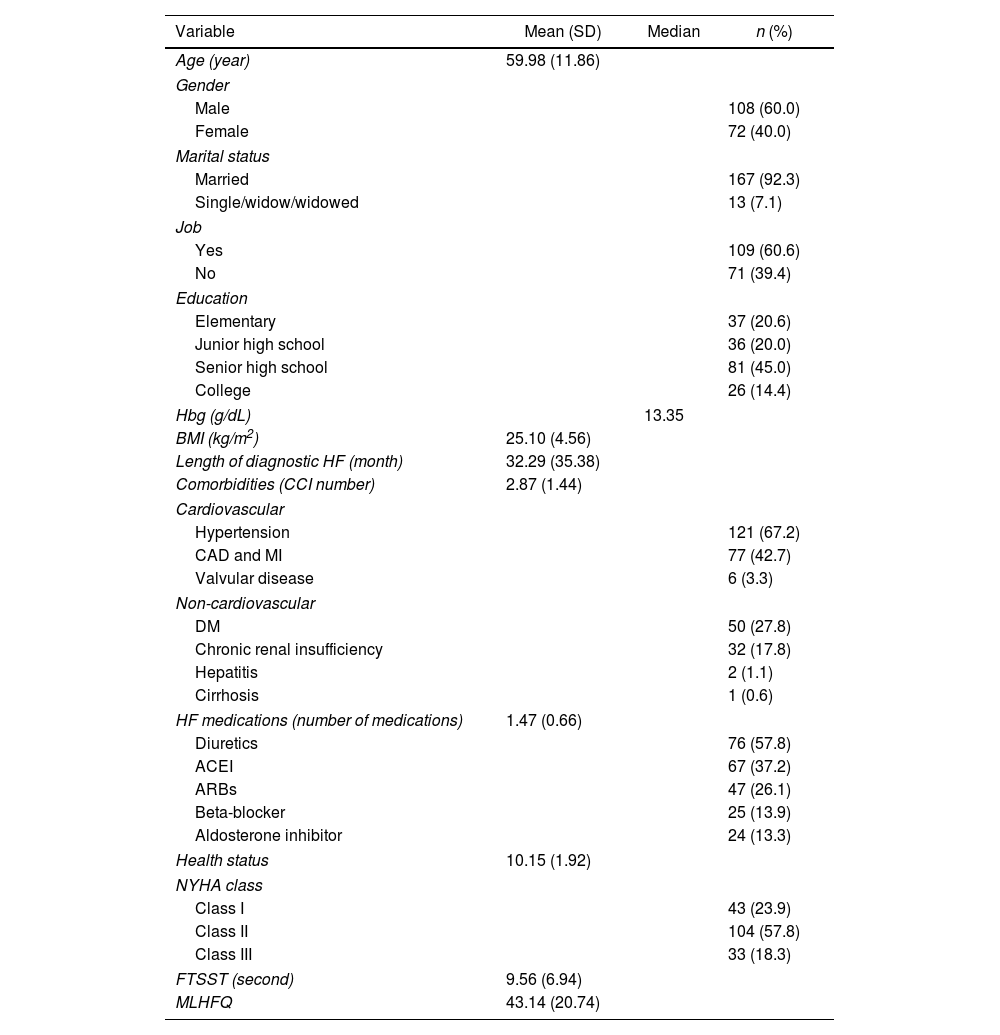

ResultsDemographic characteristics, illness-related factors, PP, and HRQOLThe demographic characteristics of the 180 patients with HF involved in this study showed that the mean age was 59.98 (11.86) years old, most of the respondents were male 60%, married 92.3%, and employed 60.6%. Approximately 45% of respondents had senior high school education and 57% had NYHA Class II. Based on illness-related factors, the mean values were as follows, body mass index 25.10 (4.56)kg/m2, length of diagnostic HF was (32.29±35.38) months, comorbidity status 2.87 (1.44), HF medication 1.47 (0.66), and the median Hbg was 13.35g/dL, with most respondents using diuretics (57.8%). Moreover, the mean HF of respondents was 10.15 (1.92), FTSST 9.56 (6.94), and the mean score of MLHFQ was 43.14 (20.74) (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics and illness-related factors (n=180).

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 59.98 (11.86) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 108 (60.0) | ||

| Female | 72 (40.0) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 167 (92.3) | ||

| Single/widow/widowed | 13 (7.1) | ||

| Job | |||

| Yes | 109 (60.6) | ||

| No | 71 (39.4) | ||

| Education | |||

| Elementary | 37 (20.6) | ||

| Junior high school | 36 (20.0) | ||

| Senior high school | 81 (45.0) | ||

| College | 26 (14.4) | ||

| Hbg (g/dL) | 13.35 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.10 (4.56) | ||

| Length of diagnostic HF (month) | 32.29 (35.38) | ||

| Comorbidities (CCI number) | 2.87 (1.44) | ||

| Cardiovascular | |||

| Hypertension | 121 (67.2) | ||

| CAD and MI | 77 (42.7) | ||

| Valvular disease | 6 (3.3) | ||

| Non-cardiovascular | |||

| DM | 50 (27.8) | ||

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 32 (17.8) | ||

| Hepatitis | 2 (1.1) | ||

| Cirrhosis | 1 (0.6) | ||

| HF medications (number of medications) | 1.47 (0.66) | ||

| Diuretics | 76 (57.8) | ||

| ACEI | 67 (37.2) | ||

| ARBs | 47 (26.1) | ||

| Beta-blocker | 25 (13.9) | ||

| Aldosterone inhibitor | 24 (13.3) | ||

| Health status | 10.15 (1.92) | ||

| NYHA class | |||

| Class I | 43 (23.9) | ||

| Class II | 104 (57.8) | ||

| Class III | 33 (18.3) | ||

| FTSST (second) | 9.56 (6.94) | ||

| MLHFQ | 43.14 (20.74) | ||

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; Hgb, hemoglobin; MI, myocardial infarction; SD, standard deviation.

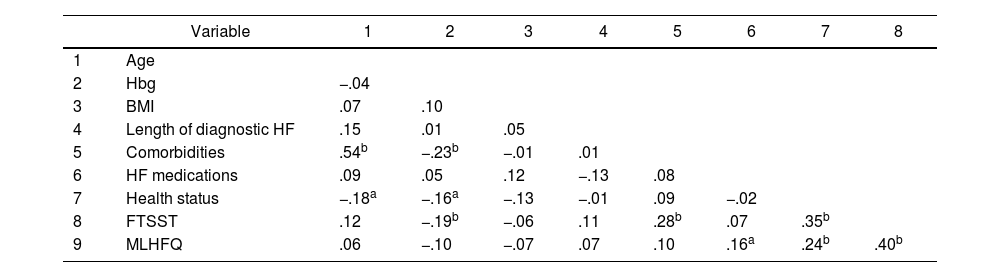

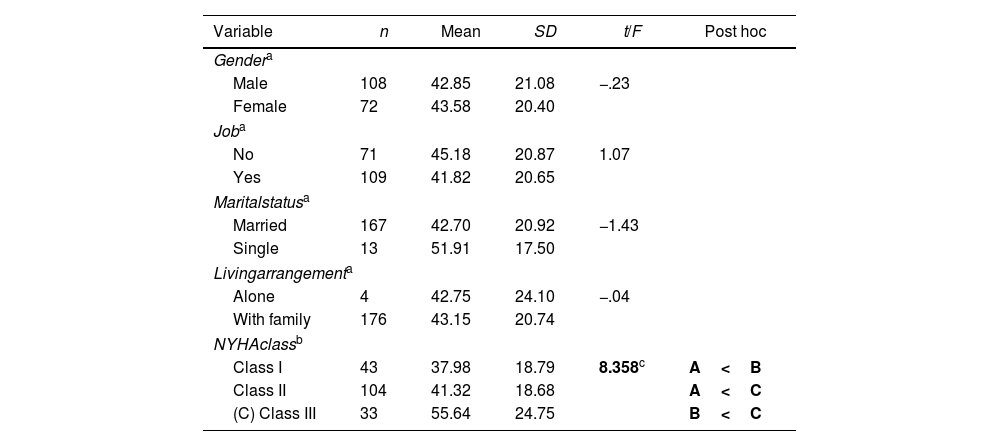

This study explained that MLHFQ of patients with HF had a significant correlation with HF medication (r=.16, P<.05), HS (r=.24, P<.01), and FTSST (r=.40, P<.01). The results showed that MLHFQ had a significant association with NYHA Classification (F=8.358, P<.001). After post hoc analysis, NYHA Class I had a lower MLHFQ score (37.98±18.79) than Class III (55.64±24.75) and Class II (41.32±18.68), while NYHA Class II had a lower MLHFQ score than Class III. However, MLHFQ did not correlate with age, gender, job, marital status, living arrangement, Hbg, body mass index, length of diagnostic HF, and comorbidity, as presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Correlation between demographic characteristics, illness-related factors, and HRQOL (n: 180).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | ||||||||

| 2 | Hbg | −.04 | |||||||

| 3 | BMI | .07 | .10 | ||||||

| 4 | Length of diagnostic HF | .15 | .01 | .05 | |||||

| 5 | Comorbidities | .54b | −.23b | −.01 | .01 | ||||

| 6 | HF medications | .09 | .05 | .12 | −.13 | .08 | |||

| 7 | Health status | −.18a | −.16a | −.13 | −.01 | .09 | −.02 | ||

| 8 | FTSST | .12 | −.19b | −.06 | .11 | .28b | .07 | .35b | |

| 9 | MLHFQ | .06 | −.10 | −.07 | .07 | .10 | .16a | .24b | .40b |

BMI, body mass index; FTSST, Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test; Hgb, hemoglobin; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire.

Association between demographic characteristics, illness-related factors, and HRQOL (n=180).

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | t/F | Post hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gendera | |||||

| Male | 108 | 42.85 | 21.08 | −.23 | |

| Female | 72 | 43.58 | 20.40 | ||

| Joba | |||||

| No | 71 | 45.18 | 20.87 | 1.07 | |

| Yes | 109 | 41.82 | 20.65 | ||

| Maritalstatusa | |||||

| Married | 167 | 42.70 | 20.92 | −1.43 | |

| Single | 13 | 51.91 | 17.50 | ||

| Livingarrangementa | |||||

| Alone | 4 | 42.75 | 24.10 | −.04 | |

| With family | 176 | 43.15 | 20.74 | ||

| NYHAclassb | |||||

| Class I | 43 | 37.98 | 18.79 | 8.358c | A<B |

| Class II | 104 | 41.32 | 18.68 | A<C | |

| (C) Class III | 33 | 55.64 | 24.75 | B<C | |

FTSST, Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; HF, heart failure; HS, health status; NYHA, New York Heart Association Classification.

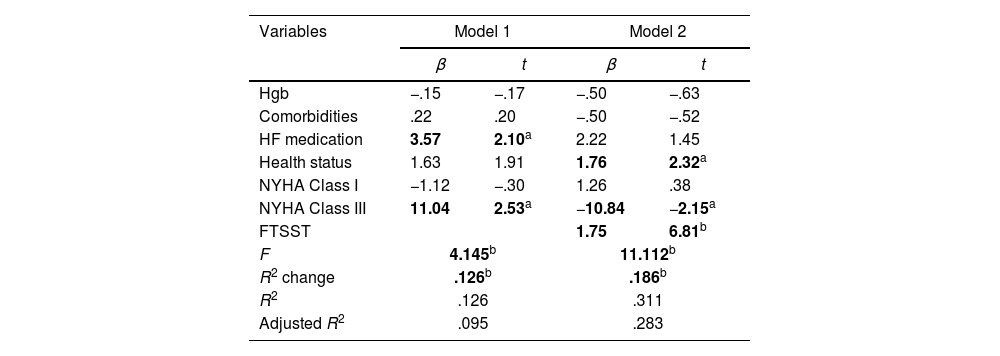

Table 4 shows that four variables that significantly correlated with MLHFQ, namely HF medication, HS, NYHA Classification, and FTSST as well as hemoglobin and comorbidity based on cut point values were included in the multiple linear regression model. In the first model, the variables included were hemoglobin, comorbidity, HF medication, HS, and dummy variables for NYHA Classification, which accounted for 12.6% of MLHFQ variance. The significant variables with MLHFQ in this model were HF medication (β=3.57, P<.05) and NYHA Class III (β=11.04, P<.05). In the second model, PP variables using FTSST were included, and the results revealed that R2 increased by 31.1% (P<.001) from .095 to .283. The significant variables were HS (β=1.76, P<.05), NYHA Class III (β=−10.84, P<.05), and FTSST (β=1.75, P<.001).

Hierarchical multiple regression of predictor variables on HRQOL (n=180).

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | |

| Hgb | −.15 | −.17 | −.50 | −.63 |

| Comorbidities | .22 | .20 | −.50 | −.52 |

| HF medication | 3.57 | 2.10a | 2.22 | 1.45 |

| Health status | 1.63 | 1.91 | 1.76 | 2.32a |

| NYHA Class I | −1.12 | −.30 | 1.26 | .38 |

| NYHA Class III | 11.04 | 2.53a | −10.84 | −2.15a |

| FTSST | 1.75 | 6.81b | ||

| F | 4.145b | 11.112b | ||

| R2 change | .126b | .186b | ||

| R2 | .126 | .311 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | .095 | .283 | ||

FTSST, Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test; HF, heart failure; Hgb, hemoglobin; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; NYHA, New York Heart Association Classification.

The average age of the respondents in this study was middle age, as supported by previous reports, where the risk of HF increased with age,18 especially in middle age.19 Most of the respondents were male, but the issue of gender differences was not yet clear in the incidence of HF.20

One of the problems that affected HRQOL was NYHA Classification.21 In this study, the average HRQOL of respondents was moderate, categorized in the NYHA Class I and II. Therefore, some may not have been bothered by HF symptoms compared to those with higher NYHA Class. These results supported the assumption that a lower NYHA Class had better HRQOL compared to a higher NYHA.21,22 Furthermore, previous studies showed that a higher NYHA Class was very influential in reducing HRQOL22,23 (Table 1 of the supplementary data).

This study revealed a significant correlation between HRQOL and HF medication, where the more patients used HF medications, the lower the impact on HRQOL. Previous investigations reported that HF medications relieved some symptoms, such as dyspnea, fatigue, and shortness of breath. However, the side effects of the medications can impact HRQOL,24 such as dry mouth, thirst, decreased blood pressure, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, as well as decreased heart rate.25–27 It was also discovered that HS played an important role in HRQOL in patients with HF, where a decrease in patients HS affected the decline in HRQOL.28

PP is one of HRQOL predictors of patients with HF and an important indicator in HRQOL.29,30 As shown in this study, where a positive correlation was found between FTSST and MLHFQ. This result identified that a decrease in PP caused a reduction in HRQOL or vice versa. Based on previous studies, PP had the potential to improve functional capacity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and exercise capacity, which played a role in improving HRQOL of patients with HF.10,11,31

HRQOL predictors of patients with HF in this study were HS, NYHA Class III, and PP using FTSST. Based on the results, PP was found to play an important role in HRQOL of patients with HF, where increasing PP from patients significantly improved HRQOL. A good HS from HF patients positively affected HRQOL, which decreased with a higher NYHA Class. Previous studies stated that enhanced PP and HS of patients with HF positively improved HRQOL, especially among those with lower NYHA Class.10,22,32

LimitationsThe limitations of this study included the distribution of respondents, with less than 50% in NYHA Class I and III. Meanwhile, in Class I, some patients did not feel the effect of HF symptoms and refrained from seeking hospital treatment. Most of the respondents in NYHA Class III were more inclined to seek treatment or visit the emergency room due to the severity of their symptoms rather than receiving outpatients care due to symptoms experienced. However, with the use of good sampling methods and data analysis, the results of this study can be trusted for accuracy. Secondly, HRQOL and PP were measured cross-sectionally, which limited the ability to determine causal relationships. The data obtained can provide evidence that PP using FTSST plays an important role in HRQOL of patients with HF. Therefore, a longitudinal study is a recommendation to determine the causal relationship between HRQOL and PP for future studies.

ConclusionsThis showed that enhancing PP of patients with HF was one of the goals of improving HRQOL apart from the therapy received routinely. Furthermore, PP, HS, and NYHA classifications needed to be considered as important factors to improve HRQOL. The results also showed the accuracy of data that can be used as a basis to improve HRQOL of patients with HF.

- •

HF is a public health issue and growing up year by year.

- •

HRQOL is an indicator of re-hospitalization and mortality rate of patients with HF.

- •

People living with HF have a trend of low HRQOL.

- •

The strategy for increasing the HRQOL of patients with HF is maintaining a good PP.

- •

Low NYHA Classification has an effect to decrease HRQOL in people living with HF.

- •

Better HS can increase the HRQOL of patients with HF.

- •

PP, NYHA Class III, and HS are predictors of HRQOL patients with HF.

This research did not receive any funding from agencies or institution.

Ethical considerationsOur study had been approved by an Ethics Committee and the institution (PP04.03/XIX.3/3580/2021). The respondents who agreed to participate were given informed consent. A cross-sectional design was employed for analysis and consecutive sampling was carried out on 180 HF patients, consisting of both male (n: 108) and female (n: 72) at the outpatients unit. The study followed the guidelines of the STROBE form.

Statement on the use of artificial intelligenceNo used artificial intelligence.

Authors’ contributionsThe first and second authors conceived of the presented idea. The first author performed the conceptualization, writing of the manuscript, and verified the analytical methods. The second author supervised the data collection. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest.