Despite evidence of a reduction in the incidence and mortality of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), some studies have highlighted differences in outcomes between men and women. We aimed to explore sex differences in the management and treatment of patients with ACS in Spain.

MethodsThis ecological cross-sectional study combined ACS data from 10 Spanish registries (54 centres). Meta-regression analysis was performed using aggregated data of baseline characteristics, interventional procedures, treatments, and events that occurred during hospitalization and one-year follow-up.

ResultsAggregated data from 34605 patients (75.1% men) was included. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was the most frequent diagnosis (58.9%) and almost 80% of patients were Killip Class I. Compared to men, women were older (mean age: 71.0 vs 63.3 years) and presented higher rates of hypertension (68.1% vs 51.7%) and diabetes (37.7% vs 26.5%). Women were also less likely to undergo percutaneous coronary interventions, revascularization surgery, and to receive drug-eluting stents during hospitalization. Regarding to antiplatelet therapy, even though indicated, 23.1% of women were not treated with P2Y12 inhibitors (vs 14.2% of men; P<.001); clopidogrel was the most frequently administered agent (> 60%). Significantly higher in-hospital (5.4% vs 3.7%) and 1-year (8.2% vs 4.9%) mortality was observed among women compared to men, which was mainly attributed to cardiovascular causes.

ConclusionsDespite older age and unfavourable risk profile, female ACS patients seem to be suboptimally treated with P2Y12 inhibitors. To reduce mortality associated with ACS, improved prevention and optimized therapeutic approaches are needed.

A pesar del descenso en la incidencia y en la mortalidad por síndrome coronario agudo (SCA), algunos estudios indican discrepancias en los resultados entre varones y mujeres. Nuestro objetivo fue investigar la influencia del sexo en el tratamiento de pacientes con SCA en España.

MétodosEstudio ecológico transversal que recogió datos de 10 registros españoles de SCA (54 centros). Se realizó un análisis de meta-regresión con datos agregados de características basales, procedimientos, tratamientos y eventos intrahospitalarios y durante un año de seguimiento.

ResultadosEn 34.605 pacientes (75,1% varones), el diagnóstico más frecuente fue infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (58,9%) y 80% fueron clase Killip I. Las mujeres presentaron mayor edad (media: 71.0 frente a 63.3 años), tasa de hipertensión (68,1% frente a 51,7%) y diabetes (37,7% frente a 26,5%) que los varones. El número de intervenciones coronarias percutáneas, cirugía de revascularización y uso de stent fármaco-activo fueron menores en las mujeres. Respecto a la terapia antiagregante, el 23,1% de mujeres no recibieron inhibidores P2Y12, aun estando indicado (frente a 14,2% de varones; p < 0,001); clopidogrel fue el más administrado (> 60%). La mortalidad intrahospitalaria (5,4% frente a 3,7%) y al año (8,2% frente a 4,9%) aumentó significativamente en las mujeres respecto a los varones, principalmente por causas cardiovasculares.

ConclusionesA pesar de su mayor edad y perfil de riesgo desfavorable, las mujeres con SCA parecen estar infratratadas con inhibidores P2Y12. Reducir la mortalidad asociada con el SCA requiere una mejor prevención y enfoques terapéuticos optimizados.

Cardiovascular diseases are a major health problem that constitute a leading cause of morbidity and mortality for both men and women worldwide.1 Whilst a reduction in the incidence and mortality of cardiovascular diseases has been reported in recent years,2,3 European data indicate that it has not been equal between men and women.4 Accordingly, several studies have reported a greater decline in acute myocardial infarction rates in male compared to female patients, who tend to present more comorbidities than their counterparts.5,6 The older age at acute coronary syndrome (ACS) onset in women, which has been attributed to the protective role of oestrogens against coronary events before menopause,7 could also explain the worse clinical outcomes found in some trials.8–10 Given that atypical symptoms of ACS are encountered more often in women than in men,5,11 this altogether contributes to misdiagnosis and delayed recognition of ischaemia.12

Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and P2Y12 adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonists has long been used in ACS to prevent adverse cardiovascular events or death.13 However, novel antithrombotic therapies developed in recent years have been associated with an increased bleeding risk,14,15 which is particularly pronounced among women.16 In line with previous evidence,17–19 female sex has been postulated as an independent predictor of short-term bleeding after acute myocardial infarction.12,16,20

Inconsistent results have been published regarding the influence of sex on ACS outcomes,11,21–24 which may be explained by the inclusion of populations with different baseline characteristics and/or variability in the methodology used for data analysis.25 Nonetheless, among patients with ACS, sex differences in the management of cardiovascular events and subsequent mortality rates remain a concern nowadays.12 Thus, emphasis should be placed on improving the identification of risk factors, early diagnosis and adequate therapeutic strategies in high-risk patients.

Previous independent studies have provided information on the epidemiology, prognosis and management of ACS in Spain.26–28 With this nationwide ecological study that collects aggregated data from ACS patients from several Spanish registries, we sought to evaluate the impact of ACS and explore sex differences associated with patient characteristics, management, and progression in a real-world setting.

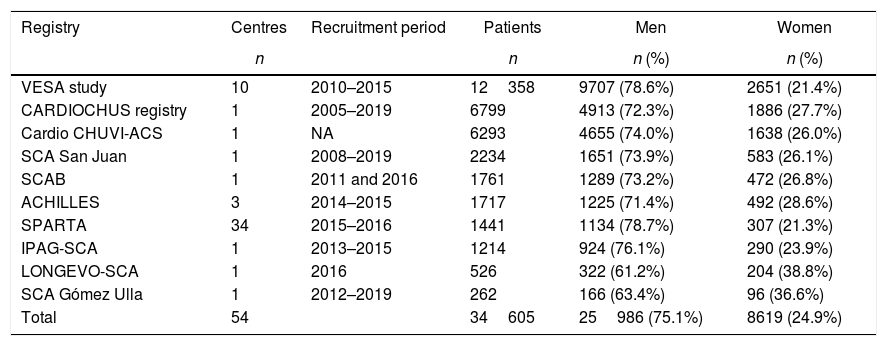

MethodsStudy design and objectivesPopulation-based ecological cross-sectional study that collected aggregated data from ten ACS patient registries across 54 centres in Spain (Table 1 and Table 1 of the supplementary data). The study population was composed of patients (men and women) hospitalized in the participant centres, who had been diagnosed with ACS (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina), and whose data were entered in the corresponding ACS registry. These registries included medical records of demographic data, risk factors and comorbidities, treatments, procedures, and events that occurred during hospitalization and one-year post-discharge. Inclusion or exclusion criteria were not established for the goal of this study.

Participant registries.

| Registry | Centres | Recruitment period | Patients | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| VESA study | 10 | 2010–2015 | 12358 | 9707 (78.6%) | 2651 (21.4%) |

| CARDIOCHUS registry | 1 | 2005–2019 | 6799 | 4913 (72.3%) | 1886 (27.7%) |

| Cardio CHUVI-ACS | 1 | NA | 6293 | 4655 (74.0%) | 1638 (26.0%) |

| SCA San Juan | 1 | 2008–2019 | 2234 | 1651 (73.9%) | 583 (26.1%) |

| SCAB | 1 | 2011 and 2016 | 1761 | 1289 (73.2%) | 472 (26.8%) |

| ACHILLES | 3 | 2014–2015 | 1717 | 1225 (71.4%) | 492 (28.6%) |

| SPARTA | 34 | 2015–2016 | 1441 | 1134 (78.7%) | 307 (21.3%) |

| IPAG-SCA | 1 | 2013–2015 | 1214 | 924 (76.1%) | 290 (23.9%) |

| LONGEVO-SCA | 1 | 2016 | 526 | 322 (61.2%) | 204 (38.8%) |

| SCA Gómez Ulla | 1 | 2012–2019 | 262 | 166 (63.4%) | 96 (36.6%) |

| Total | 54 | 34605 | 25986 (75.1%) | 8619 (24.9%) |

Our primary objective was to identify the proportion of women with ACS who are undertreated with antiplatelet agents (P2Y12 inhibitors). Secondary objectives were determined as male vs. female comparisons in (a) all-cause mortality, (b) cardiovascular-related mortality, (c) interventional procedures, (d) stroke and reinfarction, and (e) bleeding complications.

Study variablesAggregated data of patient baseline characteristics, bleeding risk, interventional procedures and events were obtained from each registry and used as variables in the analysis.

Baseline characteristics included: sex, age, weight, height, type of ACS (STEMI, non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina), Killip Class (I, II, III or IV), cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, smoking, family history of ischaemic heart disease), comorbidities (cerebrovascular accident or transient ischaemic attack, peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, dyslipidaemia, anaemia, and diabetes), prior treatments, and biochemical parameters (creatinine clearance, haemoglobin and troponin). Patients’ bleeding and ischaemic risk were estimated using the CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines)29 and GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events)30 scores, respectively.

Variables related to interventional procedures were catheterization, access site, percutaneous coronary intervention, drug-eluting stent, coronary revascularization surgery and revascularization. Events included all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality, stroke, reinfarction and bleeding complications, which were measured according the standardized criteria defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy, specifically BARC types 2 to 5.31

Statistical analysisPatient characteristics were evaluated using absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables, while mean and standard deviation (SD) were used for the continuous variables. To estimate the association between sex and binary categorical variables, analysis of binary data was performed. The odds ratio (OR) was used to measure the effect. A meta-regression model was used to find potential associations between variables, determining Wilson's or Fisher's exact test and 95% confidence interval (95%CI). The statistical analysis was carried out using STATA (version 11). A level of significance of α≤0.05 was considered for the aforementioned analyses.

Ethical statementClinical information was obtained from Spanish ACS registry databases. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with medicinal products (CEIm) of Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge (L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain); ACS registries included were previously authorized by their corresponding research ethics committees. Given that aggregated data was used for the analysis instead of individual patient records, additional informed consent was not required.

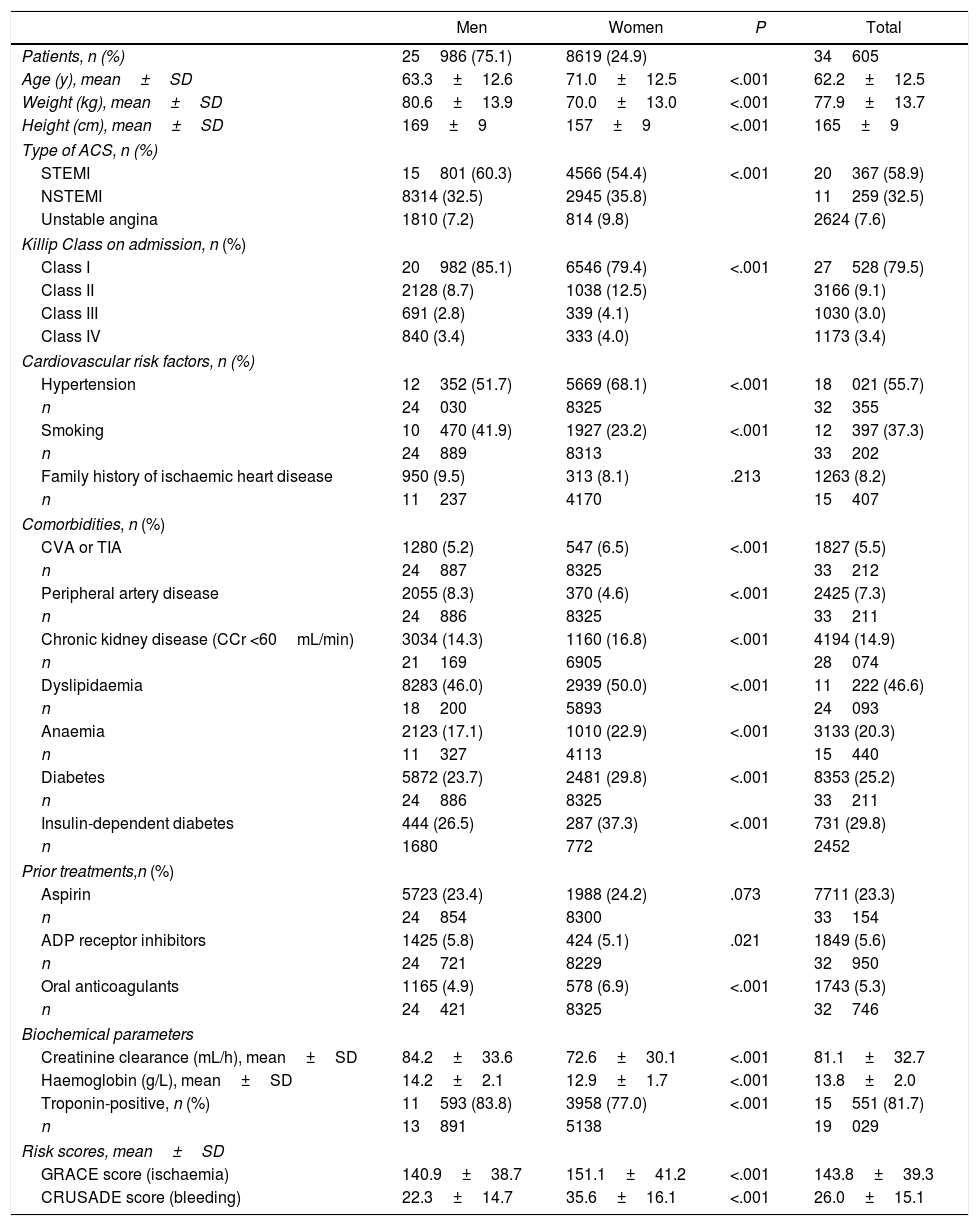

ResultsBaseline characteristicsOverall, aggregated data from 34605 patients belonging to 54 centres and ten national registries were collected (Table 1 and Table 1 of the supplementary data). Of these, 75.1% were men and 24.9% were women, with a mean age of 63.3±12.6 years and 71.0±12.6 years, respectively (Table 2). The most frequent ACS in the population was STEMI (58.9%), and nearly 80% of all patients were classified into Killip Class I on admission. Among the risk factors identified, twice as many men as women were smokers (41.9% vs. 23.2%; P<.001), whereas women presented hypertension (68.1% vs. 51.7%; P<.001) and diabetes mellitus more often (37.3% vs. 26.5%; P<.001). In contrast, despite its low frequency, peripheral artery disease was found more often in men than women (8.3% vs. 4.6%; P<.001). In terms of the most frequent comorbidities affecting both sexes similarly, 46.6% of all patients had dyslipidaemia, 20.3% had anaemia and 14.9% had chronic kidney disease.

Baseline characteristics of patients with acute coronary syndrome stratified by sex.

| Men | Women | P | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 25986 (75.1) | 8619 (24.9) | 34605 | |

| Age (y), mean±SD | 63.3±12.6 | 71.0±12.5 | <.001 | 62.2±12.5 |

| Weight (kg), mean±SD | 80.6±13.9 | 70.0±13.0 | <.001 | 77.9±13.7 |

| Height (cm), mean±SD | 169±9 | 157±9 | <.001 | 165±9 |

| Type of ACS, n (%) | ||||

| STEMI | 15801 (60.3) | 4566 (54.4) | <.001 | 20367 (58.9) |

| NSTEMI | 8314 (32.5) | 2945 (35.8) | 11259 (32.5) | |

| Unstable angina | 1810 (7.2) | 814 (9.8) | 2624 (7.6) | |

| Killip Class on admission, n (%) | ||||

| Class I | 20982 (85.1) | 6546 (79.4) | <.001 | 27528 (79.5) |

| Class II | 2128 (8.7) | 1038 (12.5) | 3166 (9.1) | |

| Class III | 691 (2.8) | 339 (4.1) | 1030 (3.0) | |

| Class IV | 840 (3.4) | 333 (4.0) | 1173 (3.4) | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 12352 (51.7) | 5669 (68.1) | <.001 | 18021 (55.7) |

| n | 24030 | 8325 | 32355 | |

| Smoking | 10470 (41.9) | 1927 (23.2) | <.001 | 12397 (37.3) |

| n | 24889 | 8313 | 33202 | |

| Family history of ischaemic heart disease | 950 (9.5) | 313 (8.1) | .213 | 1263 (8.2) |

| n | 11237 | 4170 | 15407 | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| CVA or TIA | 1280 (5.2) | 547 (6.5) | <.001 | 1827 (5.5) |

| n | 24887 | 8325 | 33212 | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2055 (8.3) | 370 (4.6) | <.001 | 2425 (7.3) |

| n | 24886 | 8325 | 33211 | |

| Chronic kidney disease (CCr <60mL/min) | 3034 (14.3) | 1160 (16.8) | <.001 | 4194 (14.9) |

| n | 21169 | 6905 | 28074 | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 8283 (46.0) | 2939 (50.0) | <.001 | 11222 (46.6) |

| n | 18200 | 5893 | 24093 | |

| Anaemia | 2123 (17.1) | 1010 (22.9) | <.001 | 3133 (20.3) |

| n | 11327 | 4113 | 15440 | |

| Diabetes | 5872 (23.7) | 2481 (29.8) | <.001 | 8353 (25.2) |

| n | 24886 | 8325 | 33211 | |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 444 (26.5) | 287 (37.3) | <.001 | 731 (29.8) |

| n | 1680 | 772 | 2452 | |

| Prior treatments,n (%) | ||||

| Aspirin | 5723 (23.4) | 1988 (24.2) | .073 | 7711 (23.3) |

| n | 24854 | 8300 | 33154 | |

| ADP receptor inhibitors | 1425 (5.8) | 424 (5.1) | .021 | 1849 (5.6) |

| n | 24721 | 8229 | 32950 | |

| Oral anticoagulants | 1165 (4.9) | 578 (6.9) | <.001 | 1743 (5.3) |

| n | 24421 | 8325 | 32746 | |

| Biochemical parameters | ||||

| Creatinine clearance (mL/h), mean±SD | 84.2±33.6 | 72.6±30.1 | <.001 | 81.1±32.7 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L), mean±SD | 14.2±2.1 | 12.9±1.7 | <.001 | 13.8±2.0 |

| Troponin-positive, n (%) | 11593 (83.8) | 3958 (77.0) | <.001 | 15551 (81.7) |

| n | 13891 | 5138 | 19029 | |

| Risk scores, mean±SD | ||||

| GRACE score (ischaemia) | 140.9±38.7 | 151.1±41.2 | <.001 | 143.8±39.3 |

| CRUSADE score (bleeding) | 22.3±14.7 | 35.6±16.1 | <.001 | 26.0±15.1 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; CCr, creatinine clearance; CRUSADE, Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines; CVA, cerebrovascular accident (acute stroke); GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischaemic attack (ministroke).

Some differences were found in previous treatments regarding the use of adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitors and oral anticoagulants, although aspirin was administered more often overall (23.3% vs. 5.6% adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitors vs. 5.3% oral anticoagulants) and similarly across groups. Regarding biochemical parameters, higher creatinine clearance, haemoglobin and positive troponin levels were encountered in men. Conversely, increased ischaemic and bleeding risk, as determined by the GRACE and CRUSADE scores, respectively, were found among women.

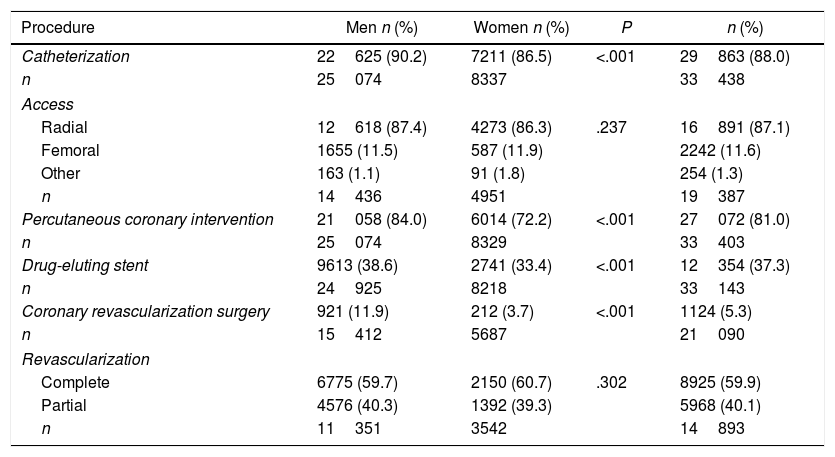

Procedures during hospitalizationProcedural characteristics are summarized in Table 3. Catheterization and radial access were performed in the vast majority of patients regardless of sex (88.0% and 87.1%, respectively). However, despite an overall frequency of 81.0%, an 11.8% difference in favour of male patients was observed for percutaneous coronary interventions. Women were also less likely to receive a drug-eluting stent (33.4% vs. 38.6%; P<.001) or undergo coronary revascularization surgery (3.7% vs. 11.9%; P<.001).

Interventional procedures during patient hospitalization.

| Procedure | Men n (%) | Women n (%) | P | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catheterization | 22625 (90.2) | 7211 (86.5) | <.001 | 29863 (88.0) |

| n | 25074 | 8337 | 33438 | |

| Access | ||||

| Radial | 12618 (87.4) | 4273 (86.3) | .237 | 16891 (87.1) |

| Femoral | 1655 (11.5) | 587 (11.9) | 2242 (11.6) | |

| Other | 163 (1.1) | 91 (1.8) | 254 (1.3) | |

| n | 14436 | 4951 | 19387 | |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 21058 (84.0) | 6014 (72.2) | <.001 | 27072 (81.0) |

| n | 25074 | 8329 | 33403 | |

| Drug-eluting stent | 9613 (38.6) | 2741 (33.4) | <.001 | 12354 (37.3) |

| n | 24925 | 8218 | 33143 | |

| Coronary revascularization surgery | 921 (11.9) | 212 (3.7) | <.001 | 1124 (5.3) |

| n | 15412 | 5687 | 21090 | |

| Revascularization | ||||

| Complete | 6775 (59.7) | 2150 (60.7) | .302 | 8925 (59.9) |

| Partial | 4576 (40.3) | 1392 (39.3) | 5968 (40.1) | |

| n | 11351 | 3542 | 14893 | |

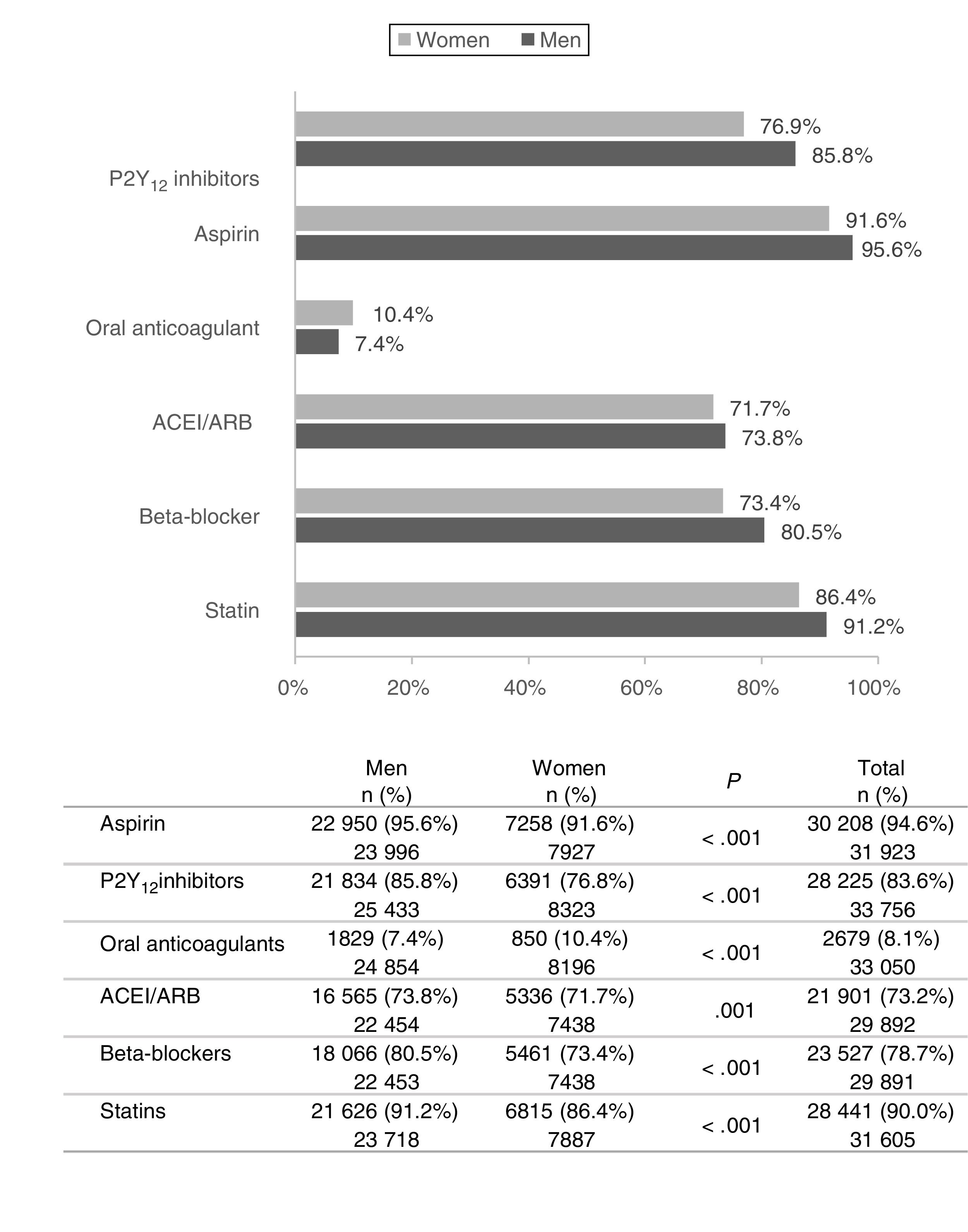

The majority of patients (≥90%) were treated with aspirin and/or statins at discharge (Fig. 1). Frequently used medication included angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (>70% of patients), and P2Y12 inhibitors and beta-blockers (>78% of patients). However, significant variations were encountered between sexes, particularly in the case of P2Y12 inhibitors and beta-blockers: a 7–10% difference was observed in favour of men compared to women. Overall, female patients were less likely to receive all these pharmacological treatments, with the sole exception of oral anticoagulants, which were administered to 10.4% women vs. 7.4% men (P<.001).

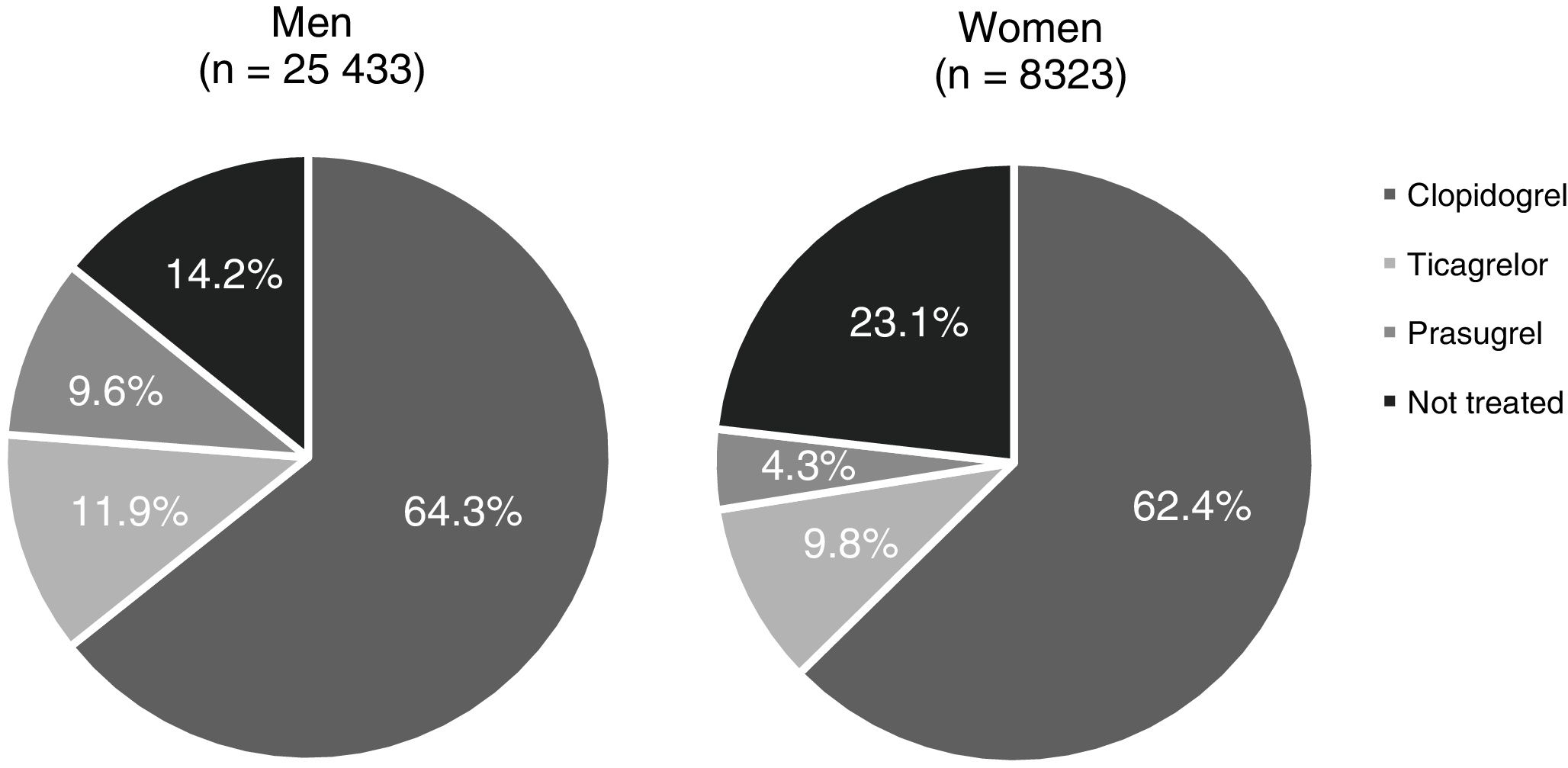

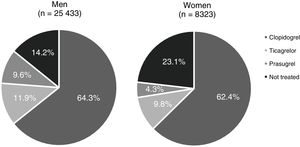

A total of 23.1% of women (95%CI, 19.6–26.8) appeared to be undertreated with P2Y12 inhibitors despite having this indication (Fig. 2), showing a statistically significant difference compared to men (OR, 14.2%; 95%CI, 13.1–15.3; P<.001). Among P2Y12 inhibitors, clopidogrel was used more often than ticagrelor or prasugrel irrespective of patients’ sex (64.3%, 11.9% and 9.6% in treated men vs. 62.4%, 9.8% and 4.3% in treated women, respectively).

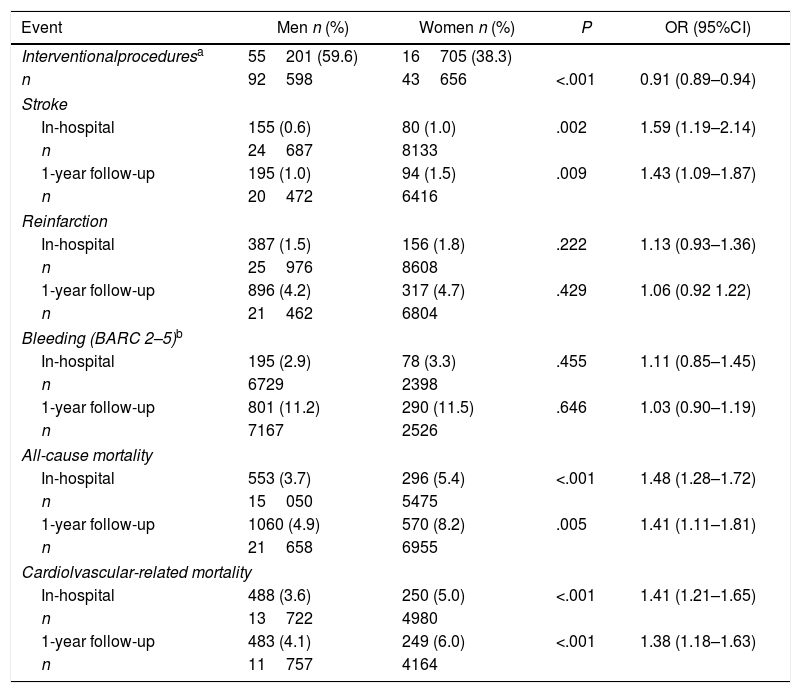

In-hospital and follow-up eventsA comparative analysis of male and female patient aggregated data was performed for mortality (all-cause and cardiovascular-related), stroke, reinfarction and bleeding episodes, both during the index hospitalization and throughout the subsequent 12-month follow-up, as well as for the interventional procedures that patients underwent during hospitalization (Table 4).

Analysis of in-hospital and 1-year follow-up events by sex.

| Event | Men n (%) | Women n (%) | P | OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventionalproceduresa | 55201 (59.6) | 16705 (38.3) | ||

| n | 92598 | 43656 | <.001 | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) |

| Stroke | ||||

| In-hospital | 155 (0.6) | 80 (1.0) | .002 | 1.59 (1.19–2.14) |

| n | 24687 | 8133 | ||

| 1-year follow-up | 195 (1.0) | 94 (1.5) | .009 | 1.43 (1.09–1.87) |

| n | 20472 | 6416 | ||

| Reinfarction | ||||

| In-hospital | 387 (1.5) | 156 (1.8) | .222 | 1.13 (0.93–1.36) |

| n | 25976 | 8608 | ||

| 1-year follow-up | 896 (4.2) | 317 (4.7) | .429 | 1.06 (0.92 1.22) |

| n | 21462 | 6804 | ||

| Bleeding (BARC 2–5)b | ||||

| In-hospital | 195 (2.9) | 78 (3.3) | .455 | 1.11 (0.85–1.45) |

| n | 6729 | 2398 | ||

| 1-year follow-up | 801 (11.2) | 290 (11.5) | .646 | 1.03 (0.90–1.19) |

| n | 7167 | 2526 | ||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| In-hospital | 553 (3.7) | 296 (5.4) | <.001 | 1.48 (1.28–1.72) |

| n | 15050 | 5475 | ||

| 1-year follow-up | 1060 (4.9) | 570 (8.2) | .005 | 1.41 (1.11–1.81) |

| n | 21658 | 6955 | ||

| Cardiolvascular-related mortality | ||||

| In-hospital | 488 (3.6) | 250 (5.0) | <.001 | 1.41 (1.21–1.65) |

| n | 13722 | 4980 | ||

| 1-year follow-up | 483 (4.1) | 249 (6.0) | <.001 | 1.38 (1.18–1.63) |

| n | 11757 | 4164 | ||

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; OR, odds ratio.

Interventional procedures included: catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention, drug-eluting stent, and coronary revascularization surgery. Patients may have undergone one or more interventional procedures. Aggregated data of all procedures performed in the entire population is depicted; individual patient information cannot be extracted.

Overall, an increased frequency of events was observed in female compared to male patients. Significantly higher rates of both all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality were observed in women compared to men, both during hospitalization (OR, 1.48; 95%CI, 1.28–1.72; and OR, 1.41; 95%CI, 1.21–1.65, respectively; P<.001) and follow-up (OR, 1.41; 95%CI, 1.11–1.81]; P=.005; and OR, 1.38; 95%CI, 1.18–1.63; P<.001, respectively). In all cases, mortality (range: 3.7% to 8.2%) was mainly associated with cardiovascular causes (range: 3.6% to 6.0%). Moreover, interventional procedures were performed significantly less often in women than men, accounting for a 12% difference between sexes.

Bleeding, according to BARC 2–5, was more frequently encountered in inpatients compared to other events, such as reinfarction or stroke, regardless of sex. Whilst stroke was the lowest reported event (≤1.5%), either during hospitalization or thereafter, it occurred significantly more often among women (OR, 1.59; 95%CI, 1.19–2.14; P=.002; and OR, 1.43; 95%CI 1.09–1.87; P=.009, respectively).

DiscussionDespite the progress made using intensive therapeutic approaches in line with practice guidelines, which has led to a reduction in in-hospital mortality and associated complications,27,32 an increase in the incidence of ACS is expected over the coming decades in Spain.28 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first analysis carried out with ACS data from Spanish registries. We collected aggregated data from the medical records of 34605 patients with ACS from a total of ten nationwide registries comprising 54 centres. Although an increasing incidence of non-ST-segment elevation – ACS has been previously reported in epidemiology studies,28,33 the most frequent type of ACS among registered patients was STEMI. In line with published evidence,5,20,34 women seemed to be older and to present an overall higher rate of risk factors and comorbidities than men. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure and chronic kidney disease, along with older age, have been reported to be more frequent among women.5,20,34

Our analysis indicated that most patients (>86%) underwent catheterization and radial access during hospitalization. Radial over femoral access is recommended by the European Society of Cardiology (ECS) guidelines for coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention, to minimize bleeding in patients with ACS who are treated with dual antiplatelet therapy (evidence class I, level A).35 In contrast, our results suggest that women were less likely to undergo other cardiac procedures, such as percutaneous coronary intervention, use of drug-eluting stents and coronary revascularization surgery, which is consistent with previous evidence.19,36,37 Although the percentage of interventional procedures appeared lower overall than recently reported in Europe,38 which may be related to the use of old registries for our analysis, notable sex-related differences were identified.

For ACS, a dual antiplatelet therapy consisting of treatment with aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor, is usually recommended for at least 12 months,39,40 considering shorter durations for patients with high-risk bleeding.41,42 Most patients (>90%) received aspirin and/or statins at discharge. P2Y12 inhibitors and beta-blockers were also highly prescribed for ACS (>78%), although substantial differences could be observed between female and male patients. Despite the indications in current guidelines,39,40 a significant number of women appeared undertreated with P2Y12 inhibitors at discharge (23.1% vs. 14.2% undertreated men). These observations are consistent with results from previous studies,5,25,43 thereby highlighting sex-related disparities in the therapeutic management of ACS patients.

Although clopidogrel has long been used as dual antiplatelet therapy to prevent death or adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events in patients with ACS,13,44 the novel P2Y12 inhibitors ticagrelor and prasugrel have shown superior efficacy.14,15 Despite the preference for prasugrel and ticagrelor over clopidogrel in current ESC guidelines,35 our results suggest that clopidogrel was the most frequently administered P2Y12 inhibitor in ACS patients, regardless of sex, in Spain. This may be due to the time period when data were collected and the inclusion of aggregated data collected by the individual registries before the establishment of current ECS guidelines, but it could also underscore a failure to prescribe novel antiplatelet agents in our setting. The significantly higher rate of anaemia among women compared to men might have also led to the prescription of more conservative antiplatelet therapies.

Given its association with worse outcomes and mortality rates, bleeding constitutes the most frequent non-ischaemic complication in ACS patients.34 Moreover, the novel antiplatelet therapies that have emerged in recent years have been linked to an increased risk of bleeding in these patients.14,15 Some studies have described female sex as an independent predictor of non-surgery related bleeding.17,18,39,45,46 Likewise, an increased bleeding risk, according to the CRUSADE score, was observed in women compared to men in our study. However, this observation did not translate into a statistically significant difference in terms of the number of bleeding events, either during hospitalization or thereafter. While the incidence of bleeding events from discharge to the end of follow-up was in line with the literature,34 a lower number of in-hospital events, likely due to misregistration and subsequent underestimation, was observed among the ACS population in this study.

Overall, a higher frequency of in-hospital and follow-up events were encountered in women with ACS compared to men, with significantly increased all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality. Whilst these rates seemed lower than those reported in a recent study of women with STEMI (16.9%) and non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (11.7%) during hospitalization,20 our results support the association between sex and unfavourable outcome in ACS.5,17,18,34,39,45,46 In contrast, no sex-related differences were observed in the frequency of reinfarction or bleeding during follow-up in this patient population. Regarding the risk of ischaemia, which was significantly higher among women at baseline, some studies have reported an increased long-term risk compared to bleeding in patients with prior myocardial infarction treated with P2Y12 inhibitors.47,48 Hence, given the importance of both bleeding and ischaemic events in the patient's prognosis, emphasis should be placed on individual risk assessments in order to adopt preventive strategies and more adequate therapeutic approaches.34,41,42

LimitationsOur study has certain limitations that should be taken into consideration, as they could explain the aforementioned discrepancies with previous publications. First, although we have attempted to homogenize data from the ten registries, heterogeneity cannot be completely ruled out. Registries included in this study differed in patient inclusion criteria, particularly for the time of inclusion, which may have partially biased some of the results (e.g. the use of drug-eluting stents and the extremely low percentage of patients using newer and more potent P2Y12 inhibitors, as well as the higher proportion of STEMI cases in our population compared to literature). Second, given the observational nature of this study, inherent differences may be found in some of the variables evaluated. Since individualized patient data could not be analyzed, it is not possible to examine the causality of events. Third, patients may have presented certain clinical features, experienced events (i.e. in-hospital mortality) or undergone interventional procedures that have not been documented. While mortality and reinfarction are variables that could be easily extracted from electronic medical records, some events, such as mild or minor bleeding, are not always reported by the patient or properly recorded. Moreover, the use of different scores hindered data analysis of some variables, such as bleeding complications. The limitations addressed herein may serve to improve data collection on ACS in Spain, which should be driven by an increased effort to register these cases, along with standardization of patient evaluation criteria.

ConclusionsThe results of this ecological cross-sectional study suggest that 23.1% of women with ACS may be undertreated with P2Y12 inhibitors in Spain. Despite current recommendations in clinical practice guidelines on the use of ticagrelor or prasugrel as first-line therapy for ACS, clopidogrel appeared to be the most frequently used antiplatelet agent, regardless of sex. Older age and unfavourable risk profile of women could be associated with increased mortality rates, both during hospitalization and at follow-up. Thus, emphasis should be placed on improved ACS prevention strategies and optimized therapeutic approaches in women. Growing awareness of sex differences in the management and importance of adherence to appropriate treatments are needed to improve both ischaemic and bleeding outcomes in female and male patients with ACS.

- •

ACS is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in men and women, with the incidence expected to increase in the coming years.

- •

Women with ACS usually are older at onset, and present atypical symptoms and unfavourable risk profile. Higher mortality rates and bleeding complications have been reported in female compared to male patients.

- •

Although the available evidence is mixed, sex-related differences in the management and treatment of ACS could explain women's poorer clinical outcomes.

- •

This ecological cross-sectional study included aggregated data from 34605 patients (75% men) from 10 ACS registries and 54 centres in Spain.

- •

A trend towards a greater burden of risk factors, more comorbidities and bleeding risk was observed in women.

- •

Despite being indicated, over 23% of women were not treated with P2Y12 inhibitors at discharge. Clopidogrel was the P2Y12 antagonist most often administered.

- •

Women seemed less likely to undergo interventional procedures. Mortality and stroke were significantly more frequent in female patients, both during hospitalization and follow-up.

This work was sponsored by the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC). Funding to perform the study was obtained from an unconditioned grant from AstraZeneca.

Conflicts of interestJ.M. Ruiz-Nodar has received honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca, Biosensor, Boston Scientific, Medtronic and Terumo. J.L. Ferreiro has received honoraria for lectures from Eli Lilly and Company, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Roche Diagnostics, Pfizer, Abbott Laboratories, Boehringer Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers Squibb, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and research grants from AstraZeneca. A. Cordero has received honoraria from lectures and consulting fees from AstraZeneca and AMGEN, honoraria for lectures from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and consulting fees from Ferrer Internacional. V. Bertomeu-González has received honoraria from lectures from Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Pfizer, LivaNova, Sanofi, and Ferrer Internacional. F. Marín Ortuño has received research grants from Fundación para la Investigación de la Región de Murcia (FFIS) and AstraZeneca, and honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Pfizer-BMS. M. Almendro-Delia has received honoraria for lectures from Eli Lilly and Company, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer International, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Hispania, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Bayer Hispania, and research grants from AstraZeneca. A. Valls-Serral has received honoraria for lectures and/or consulting from Novartis, AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. A. Cequier has received research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Biosensors, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Biomenco, Cordis, Orbus Neich, and the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC), and honoraria from Abbott Laboratories, Biosensors, Medtronic, Ferrer International, Terumo, AstraZeneca and Biotronik.

S. Raposeiras-Roubín is associate editor of REC: CardioClinics. The journal's editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed.

D. Martí Sánchez has received honoraria from AstraZeneca. A. Ribera, J.R. Marsal, J.M. García Acuña, R. Agra Bermejo, E. Abu-Assi, A. Chacón Piñero, J.M. Nogales-Asensio, M.A. Esteve-Pastor, P.L. Sánchez, F. Fernández-Avilés, J.C. Gómez Polo, A. Viana Tejedor, A. Ariza Solé, J. Sanchis, D. Carballeira Puentes, M. Santás-Álvarez, I. Lozano, M. Anguita declares no conflict of interest.

The authors thank Celia Miguel Blanco at MS-C (Valencia, Spain) for editorial support in writing of this manuscript.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.rccl.2020.10.009.