Sacubitril/valsartan (SV) is recommended in patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. However, the characteristics of the centers included in the pivotal clinical trial differ from real life. The present study aims to analyze the clinical profile of patients treated with SV according to hospital type and the potential role of these differences in drug safety and effectivity.

MethodsProspective multicenter registry that included outpatients treated with SV. We compared baseline characteristics and treatments, drug titration, and data at 7-months follow-up according to hospital type.

ResultsFrom 427 patients, 81 (19%) were included in medium/small size hospitals, 204 (48%) in heart transplant program centers and 142 (33%) in hospitals with ≥1000 beds without heart transplant program. A low starting dose of SV (50mg bid) was more frequent in medium/small size hospitals than in hospitals with ≥1000 beds (51 [63.0%] vs 151 [43.6%] patients, P=.008). At 7 months, SV had been withdrawn more frequently in medium/small size hospitals than in hospitals ≥1000 beds (15 [18.5%] vs 34 [9.8%] patients, P=.001], in spite of a similar rate of adverse events (23 [28.4%)] vs 99 [28.6%] patients, P=.94).

ConclusionIn our registry, the use of SV in real life showed a low rate of events during follow-up. The above suggests that this drug is safe and beneficial in different clinical profiles of patients but drug withdrawal is more frequent in medium/small size hospitals.

Se recomienda el sacubitrilo-valstartán (SV) en pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca y fracción de eyección reducida. Sin embargo, las características de los centros incluidos en los ensayos clínicos fundamentales son diferentes a las de los centros en la vida real. El objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar el perfil clínico de los pacientes tratados con SV según el tipo de hospital y el papel potencial de estas diferencias en la seguridad y la efectividad de este fármaco.

MétodosRegistro multicéntrico prospectivo que incluyó a pacientes ambulatorios tratados con SV. Se compararon las características basales y los tratamientos, la dosificación del fármaco y los datos a los 7 meses de seguimiento.

ResultadosDe 427 pacientes, 81 (19,0%) se incluyeron en hospitales de tamaño medio/pequeño, 204 (48%) en centros con programa de trasplante cardiaco y 142 (33%) en hospitales con ≥ 1.000 camas sin trasplante cardiaco. Una dosis de inicio baja de SV fue más frecuente en hospitales de tamaño medio/pequeño que en hospitales con ≥ 1.000 camas (51 [63,0%] frente a 151 [43,6%] pacientes, p = 0,008). A los 7 meses, el SV se había retirado con mayor frecuencia en hospitales de tamaño medio/pequeño que en hospitales ≥ 1.000 camas (15 [18,5%] frente a 34 [9,8%] pacientes, p = 0,001], a pesar de una tasa similar de eventos adversos (23 [28,4%)] frente a 99 [28,6%] pacientes, p = 0,94).

ConclusiónEn nuestro estudio, el uso de SV en la vida real mostró una tasa baja de eventos en el seguimiento. Esto sugiere que este fármaco es seguro y beneficioso en diferentes perfiles clínicos de pacientes, si bien el fármaco se suspendió con mayor frecuencia en los hospitales de tamaño medio/pequeño.

Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome and a serious public health problem due to its high prevalence and poor prognosis.1–4 It is a frequent cause of hospital admission and resources consumption.5,6 The PARADIGM-HF trial (Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure)7 was a recent milestone in the pharmacological therapy of heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.8 This trail showed that, in symptomatic patients, sacubitril/valsartan (SV) achieved a greater reduction in cardiovascular mortality and heart failure admissions than enalapril. For this reason, the switch from angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers to SV is now recommended in clinical practice guidelines in symptomatic patients that present heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.9,10 Recently an expert consensus has been published indicating that the initiation of SV may be considered for naïve patients hospitalized.11 Despite these results, the characteristics of patients included in clinical trials are frequently different from real life.12 The present study aims to analyze the clinical profile of patients treated with SV according to hospital type. We also studied the potential role of these differences and of hospital characteristics in drug safety and effectivity.

MethodsWe performed a multicenter and prospective registry including all adults that received SV as outpatients and accepted the participation in the study in 10 hospitals from Madrid (Spain). This study was carried out between October 1, 2016 (date of commercialization of SV in Spain) and March 31, 2017. The recruitment was performed sequentially. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a) SV initiation during hospital admission and b) refusing to sign the informed consent. Patients were monitored in routine visits or with scheduled telephone visits during the follow-up period (7.0±0.1 months). There were no patient losses.

Assessed variables included demographic and clinical characteristics, heart failure treatment, laboratory results, left ventricular ejection fraction, variables related to SV (discontinuation rate, initial dose, and dose at the end of follow-up), vital status, and hospital readmissions during follow-up. Baseline characteristics and treatments, drug titration and data at 7 months follow-up were compared according to hospital type.

Hospitals in the registry were grouped as follows: 3 centers with heart transplant program that included 204 patients, 2 hospitals with ≥1000 beds without heart transplant program that included 142 patients, and 5 medium/small-sized hospitals that included 81 patients.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of good clinical practice. All subjects gave written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon, Madrid, Spain.

Statistical methodsCategorical data are shown as frequencies/percentages and were compared with the Chi-square test and the Fischer exact test. Continuous variables are summarized using the mean±standard deviation or as the median and interquartile range if they do not follow the normal distribution determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit test. Continuous variables were compared with ANOVA for the comparison of means or the Wilcoxon rank sum in non-parametric data. The analysis of independent predictors of SV starting dose, performed using a logistic regression model has been previously published13 and showed an independent association with the type of center. The regression model used an inclusion P threshold<.05 and an exclusion P threshold>.1. For all statistical analysis, Stata package version 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, United States) was used.

ResultsA total of 427 outpatients were recruited during the inclusion period. In 346 patients (81.0%) SV was initiated in hospitals with ≥ 1000 beds (204 in centers with heart transplant program and 142 in centers without heart transplant program) and in 81 patients (19.0%) in medium/small size hospitals.

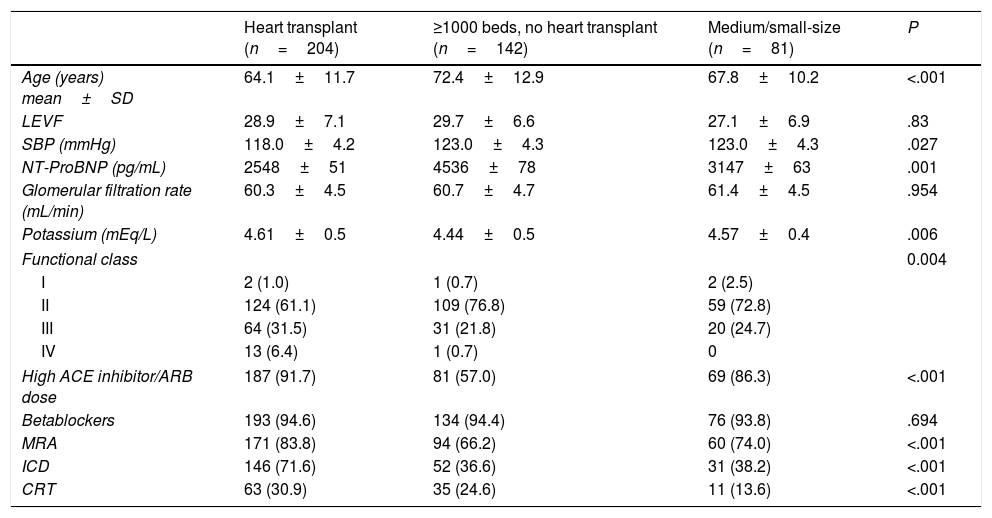

The baseline characteristics and the heart failure treatment according to hospital type are summarized in Table 1. Significant differences were found in mean age, systolic blood pressure, potassium levels, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels at the time of inclusion, and functional class. We also found some differences regarding previous medical treatment and devices. The prevalence of cardiac devices carriers was lower in medium/small hospitals than in hospitals with ≥1000 beds (31 [38.2%} vs 198 [57.2%] patients with implanted cardioverter defibrillator, P<.001; 11 [13.6%] vs 98 [28.3%] patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy, P<.001).

Baseline characteristics and heart failure treatment according to hospital type.

| Heart transplant (n=204) | ≥1000 beds, no heart transplant (n=142) | Medium/small-size (n=81) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) mean±SD | 64.1±11.7 | 72.4±12.9 | 67.8±10.2 | <.001 |

| LEVF | 28.9±7.1 | 29.7±6.6 | 27.1±6.9 | .83 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 118.0±4.2 | 123.0±4.3 | 123.0±4.3 | .027 |

| NT-ProBNP (pg/mL) | 2548±51 | 4536±78 | 3147±63 | .001 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min) | 60.3±4.5 | 60.7±4.7 | 61.4±4.5 | .954 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.61±0.5 | 4.44±0.5 | 4.57±0.4 | .006 |

| Functional class | 0.004 | |||

| I | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.5) | |

| II | 124 (61.1) | 109 (76.8) | 59 (72.8) | |

| III | 64 (31.5) | 31 (21.8) | 20 (24.7) | |

| IV | 13 (6.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | |

| High ACE inhibitor/ARB dose | 187 (91.7) | 81 (57.0) | 69 (86.3) | <.001 |

| Betablockers | 193 (94.6) | 134 (94.4) | 76 (93.8) | .694 |

| MRA | 171 (83.8) | 94 (66.2) | 60 (74.0) | <.001 |

| ICD | 146 (71.6) | 52 (36.6) | 31 (38.2) | <.001 |

| CRT | 63 (30.9) | 35 (24.6) | 11 (13.6) | <.001 |

ACE, angiotensin convertor enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LEVF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NT-ProBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, SBP, systolic blood pressure, SD, standard deviation.

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean±standard deviation.

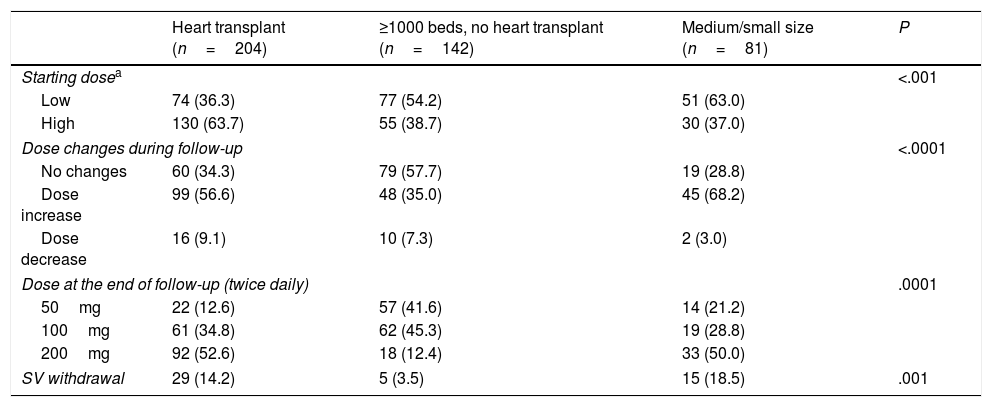

Table 2 shows the initial dose of SV, dose changes, dose at the end of the follow-up, and SV withdrawal. A low starting dose of SV (50mg bid) was more frequent in medium/small size hospitals than in hospitals with ≥1000 beds (51 [63.0%] vs 151 [43.6%] patients, P=.008). At 7 months, SV had been withdrawn more frequently in medium/small size hospitals than in hospitals ≥ 1000 (15 [18.5%] vs 34 [9.8%] patients, P=.001], in spite of a similar rate of adverse events (23 [28.4%] vs 99 [28.6%] patients, P=.94).

Titration of sacubitril/valsartan according to hospital type.

| Heart transplant (n=204) | ≥1000 beds, no heart transplant (n=142) | Medium/small size (n=81) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting dosea | <.001 | |||

| Low | 74 (36.3) | 77 (54.2) | 51 (63.0) | |

| High | 130 (63.7) | 55 (38.7) | 30 (37.0) | |

| Dose changes during follow-up | <.0001 | |||

| No changes | 60 (34.3) | 79 (57.7) | 19 (28.8) | |

| Dose increase | 99 (56.6) | 48 (35.0) | 45 (68.2) | |

| Dose decrease | 16 (9.1) | 10 (7.3) | 2 (3.0) | |

| Dose at the end of follow-up (twice daily) | .0001 | |||

| 50mg | 22 (12.6) | 57 (41.6) | 14 (21.2) | |

| 100mg | 61 (34.8) | 62 (45.3) | 19 (28.8) | |

| 200mg | 92 (52.6) | 18 (12.4) | 33 (50.0) | |

| SV withdrawal | 29 (14.2) | 5 (3.5) | 15 (18.5) | .001 |

SV, Sacubitril/valsartan.

Hospital type was an independent predictor of starting SV at a high dose (100 or 200mg bid). Hospitals with heart transplant [odds ratio (OR) 1], hospitals with ≥1000 beds, no heart transplant (OR, 0.78; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.45–1.39; P=.411), and medium/small size hospitals (OR, 0.33; 95%CI, 0.18–0.61; P<.001).

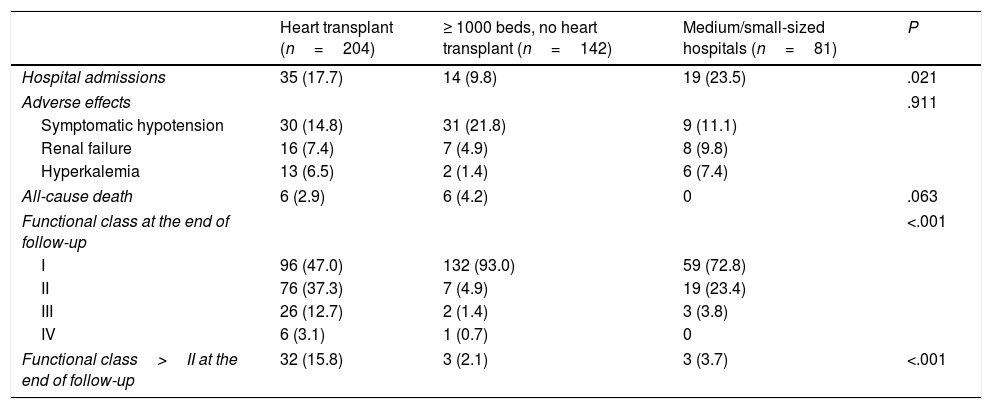

Table 3 shows the events during follow-up. Medium/small-sized hospitals had the highest number of hospital admissions, without other significant differences. Most patients were in functional class I at the end of follow-up.

Events during follow-up.

| Heart transplant (n=204) | ≥ 1000 beds, no heart transplant (n=142) | Medium/small-sized hospitals (n=81) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital admissions | 35 (17.7) | 14 (9.8) | 19 (23.5) | .021 |

| Adverse effects | .911 | |||

| Symptomatic hypotension | 30 (14.8) | 31 (21.8) | 9 (11.1) | |

| Renal failure | 16 (7.4) | 7 (4.9) | 8 (9.8) | |

| Hyperkalemia | 13 (6.5) | 2 (1.4) | 6 (7.4) | |

| All-cause death | 6 (2.9) | 6 (4.2) | 0 | .063 |

| Functional class at the end of follow-up | <.001 | |||

| I | 96 (47.0) | 132 (93.0) | 59 (72.8) | |

| II | 76 (37.3) | 7 (4.9) | 19 (23.4) | |

| III | 26 (12.7) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (3.8) | |

| IV | 6 (3.1) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | |

| Functional class>II at the end of follow-up | 32 (15.8) | 3 (2.1) | 3 (3.7) | <.001 |

Data are expressed as no. (%).

The main finding of our study was that the use of SV is safe and beneficial in different profiles of patients in real life, although medium/small size hospitals use low doses more frequently and have a higher rate of drug withdrawal than bigger centers.

Despite the euphoria generated by the results of the PARADIGM-HF trial,7 there were several unresolved issues,14 especially regarding safety, since the patient profile in real life is different from the profile seen in randomized clinical trials.15,16 In fact, in a previous work it was shown that in every-day clinical practice, SV is used more frequently in elderly patients with poor functional class.13

In hospitals with ≥ 1000 beds without a heart transplant program, older patients were included (72.4±12.9 years), and this could explain higher levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, lower rate of patients with a high angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blocker dose and lower percentage of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. This may be the reason that in this type of centers, a low starting dose of SV was used more frequently than in centers with a heart transplant program. This could justify a lower need to reduce the dose and SV withdrawal at the end of the follow-up.

We found a greater number of hospital admissions in medium/small-sized hospitals compared to the rest; however the overall 6-months mortality can be considered low (12 deaths [2.8%]), without significant differences among the groups. Medium/small size hospitals had also the highest rate of SV withdrawal (19%), as it has previously been shown that this withdrawal is associated with a poor prognosis,17 this could be a matter of concern. At 7 months, SV was removed more frequently in medium/small hospitals than in hospitals with ≥1000 beds. We must emphasize that our study began in the first 6 months of commercialization of SV in our country (when clinical experience was scarce), added to the fact that the largest hospitals have greater and better resources (heart failure units) that allow closer monitoring of the patient. This could explain the higher percentage of SV withdrawal in medium/small size hospitals. It is important to point out that no patient from medium/small hospitals died during follow-up and that only 3 (4%) had a functional class > II at the end of follow-up. So, although our data are not enough to show an independence of the type of hospital with SV withdrawal, the larger SV removal does not seem to be related with a worse clinical situation. We found a higher admission rate in heart transplant centers than in large hospitals without heart transplant program, probably related to a more complex profile and a more advanced functional class.

At the end of the follow-up, the proportion of patients in functional class > II was low in all hospitals. Taking into account that in our study there was a high percentage of patients with a baseline poor functional class, as well as a worse clinical profile than in the pivotal trial, our results suggest that SV in real life is effective in different patient profiles and in different hospital settings.

Regarding safety, symptomatic hypotension was frequent, but we did not find relevant differences among different hospital types regarding the rate of adverse events, confirming the safety of the drug in all types of centers.

Hospital type was an independent predictor of starting SV at a high dose. A high SV dose was more frequently used in hospitals with heart transplant programs, and this fact probably explains their higher downtitration rate seen during follow-up. Medium/small hospitals were those that started SV at a lower dose.

Centers≥1000 beds without heart transplant program had the lowest number of hospital admissions and the lowest rate of patients in functional class>2 at the end of follow-up. Interestingly, these were the centers with the lowest SV discontinuation rate, in probable relation with a more frequent use of low doses, suggesting that it is often preferable to maintain a low SV dose than no dose at all.

Our study has some limitations related to its observational nature. The characteristics and profile of the population may not be generalizable to other geographical areas; in particular, the majority of our patients came from university hospitals that are reference centers in heart failure, which could be susceptible to selection bias.18 This fact probably contributed to a good compliance with clinical practice guidelines. On the other hand, it is important to underline that our study is limited only to the Madrid region. Taking into account the heterogeneity of the health system between the different regions of Spain, our results may not be applicable to other health areas in the country. In addition, 7 months is a short follow-up period. Finally, our study gives important information regarding the use of SV in everyday clinical practice, a setting where information regarding this drug still is extremely scarce.19–21

ConclusionsIn our registry, the use of SV in real life showed a low rate of events during follow-up. The above suggests that this drug is safe and beneficial in different clinical profiles of patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Medium/small size hospitals use low doses more frequently and have a higher rate of drug withdrawal than high-volume centers.

- -

Sacubitril/valsartan is recommended for patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction to reduce the risk of heart failure hospitalization and death in ambulatory patients who remain symptomatic despite optimal medical treatment.

- -

However, there is a gap in patients in real life. The clinical characteristics of patients enrolled in clinical trials commonly differ from the ones found in daily clinical practice.

- -

We evaluated the clinical profile of patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan according to hospital type. We also studied the potential role of these differences and of the hospital characteristics in drug safety and effectivity.

- -

The use of sacubitril/valsartan in real life showed a low rate of events during follow-up. The above suggests that this drug is safe and beneficial in different clinical profiles of patients but drug withdrawal is more frequent in medium/small size hospitals.

- -

This supports the use of sacubitril/valsartan in our clinical practice, regardless of our hospital environment.

There has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have made substantial contributions to all of thefollowing:

1) The conception and design of the study, or acquisition ofdata, or analysis and interpretation of data.

2) Drafting the article or revising it critically for importantintellectual content.

3) Final approval of the version to be submitted.

Conflicts of interestNo conflicts of interest associated with this publication. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Abbreviation: SV: sacubitril/valsartan.