The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) has increased faster in low- and middle-income countries. We determined how the COVID-19 pandemic may have affected the relationship between income level and prevalence of DM, disease management, and the use of primary care services.

MethodsDescriptive cross-sectional study. It included diabetic patients over 14 years of age residing in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria as of 31 December 2022. The results were compared with those of a pre-pandemic study in 2019.

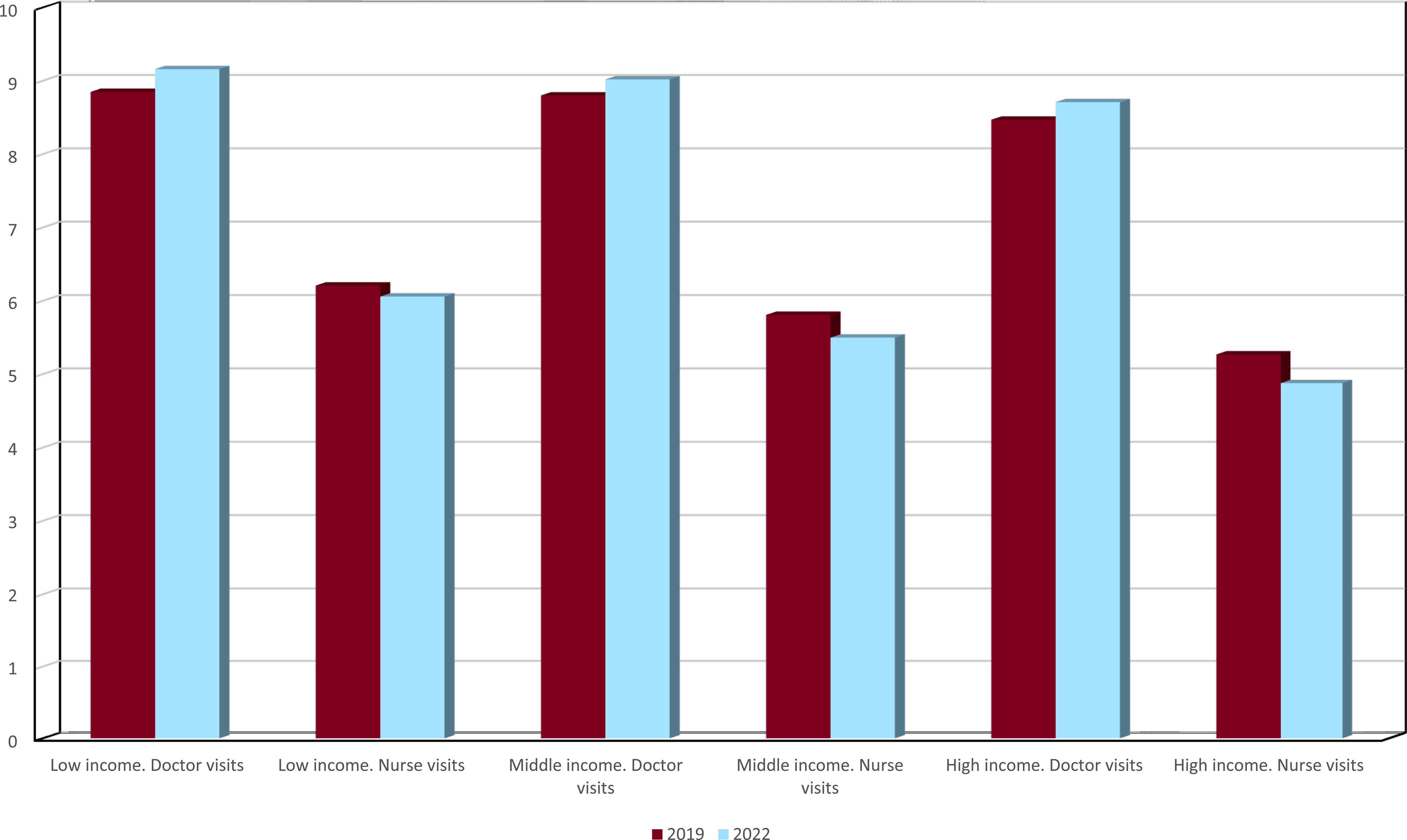

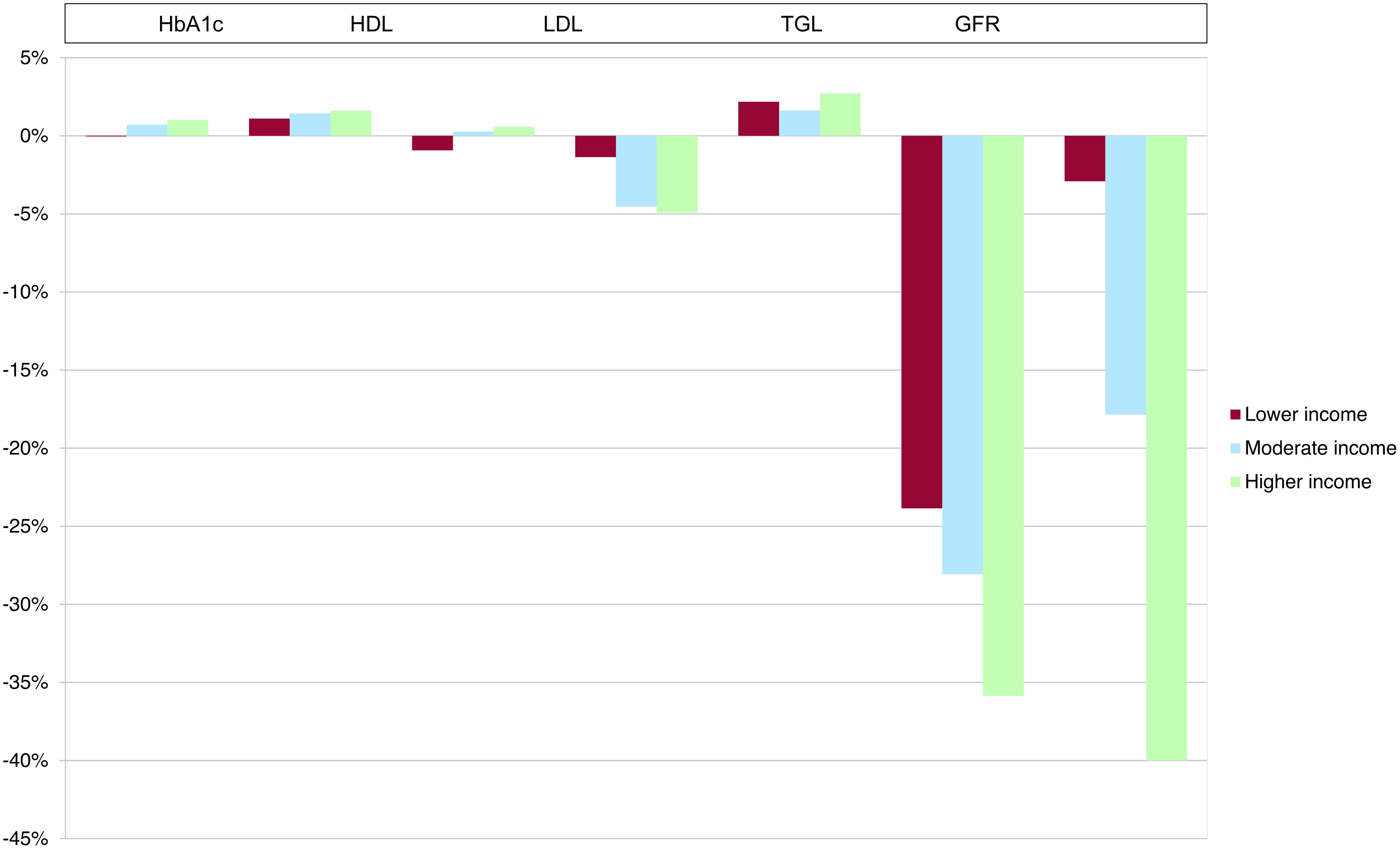

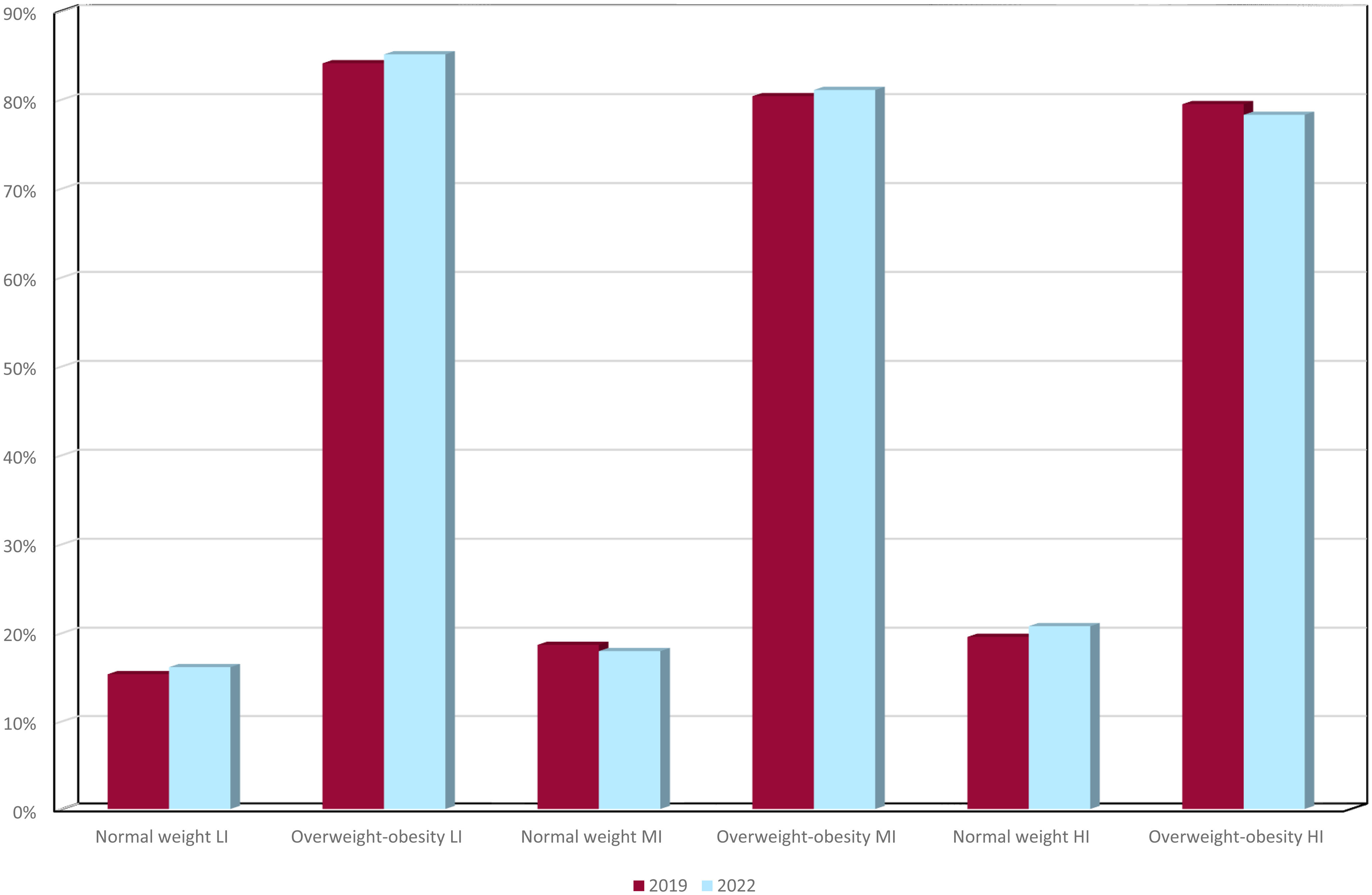

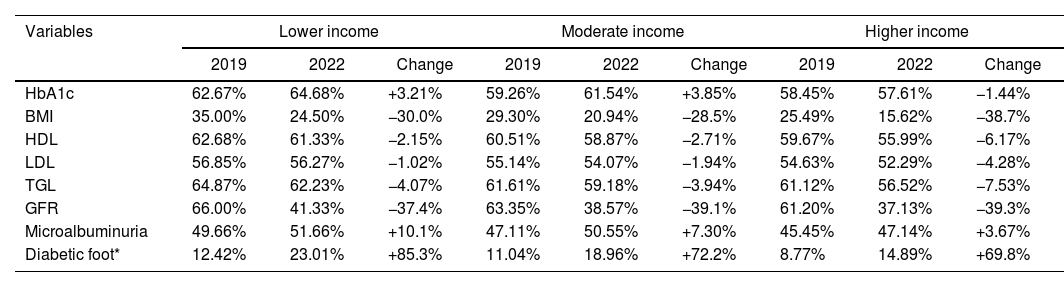

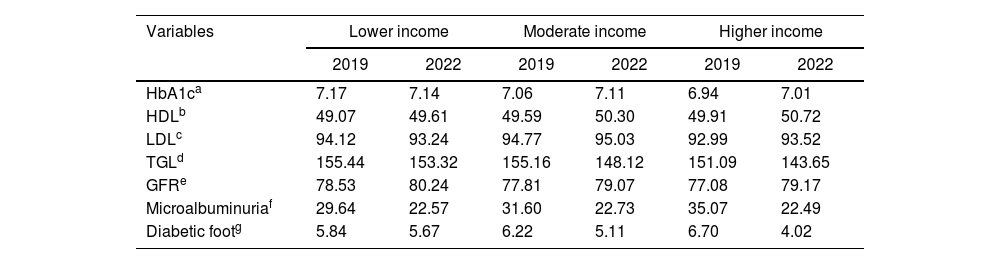

ResultsThe prevalence of DM in 2022 in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria was almost identical to that of 2019, with a slight decrease in the low- and high-income groups, and an increase in the middle-income group. The average age of the population with DM increased. The average number of visits to the doctor increased, while visits to the nursing home decreased. A worsening of glycosylated hemoglobin and low-density lipoproteins was found in high and middle incomes. The trend was the opposite for body weight, with a 1.2% increase in the prevalence of overweight/obesity in low incomes.

ConclusionsLower incomes were associated with worse outcomes in terms of overweight and obesity. The situation of people with DM with overweight or obesity worsened compared to 2019 for the lower-income population.

La prevalencia de diabetes mellitus (DM) ha aumentado más rápido en los países de ingresos bajos y medios. Se determinó cómo la pandemia de COVID-19 pudo haber afectado a la relación entre nivel de ingresos y prevalencia de DM, el abordaje de la enfermedad y el uso de los servicios de atención primaria.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo transversal. Incluyó a pacientes diabéticos mayores de 14 años residentes en Las Palmas de Gran Canaria a 31 de diciembre de 2022. Los resultados se compararon con los de un estudio previo a la pandemia de 2019.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de DM en 2022 en Las Palmas de Gran Canaria fue casi idéntica a la de 2019, con un ligero descenso en los grupos de rentas bajas y altas, y un aumento en el grupo de rentas medias. La edad media de la población con DM aumentó. El número medio de visitas al médico aumentó, mientras que las visitas a enfermería disminuyeron. Se encontró un empeoramiento de la glucohemoglobina y las lipoproteínas de baja densidad en los ingresos altos y medios. La tendencia fue la opuesta para el peso corporal, con un aumento del 1,2% en la prevalencia de sobrepeso/obesidad en los ingresos bajos.

ConclusionesLos ingresos más bajos se asociaron a peores resultados en materia de sobrepeso y obesidad. La situación de las personas con DM con sobrepeso u obesidad empeoró en comparación con 2019 para la población de menores ingresos.

Artículo

REC: CardioClinics

Use datos de acceso a SEC en el menú Acceder.

Si es socio de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología y no puede acceder con sus claves, escriba a rec@cardioclinics.org.

Use the Society's website login and password here.

If you are member of SEC and you have some problems with your login data, please contact with rec@cardioclinics.org.

Si ya tiene sus datos de acceso, clique aquí.

Si olvidó su clave de acceso puede recuperarla seleccionando la opción "He olvidado mi contraseña".Comprando el artículo el PDF del mismo podrá ser descargado

Precio 19,34 €

Comprar ahora