Controlling low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels reduces atherosclerotic risk in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. However, not all available therapies provide the same efficacy or safety outcomes, influencing treatment preferences. Our study aimed to identify patients’ and healthcare professionals’ (HCP) preferences for the attributes related to lipid-lowering therapies (LLT).

MethodsA literature review and 2 focus groups (patients=4; HCP=8), were conducted to identify LLT attributes and levels. A total of 5 attributes with 2 or 3 levels each resulted in 36 scenarios. The relative importance given to each attribute was estimated using a conditional logit model.

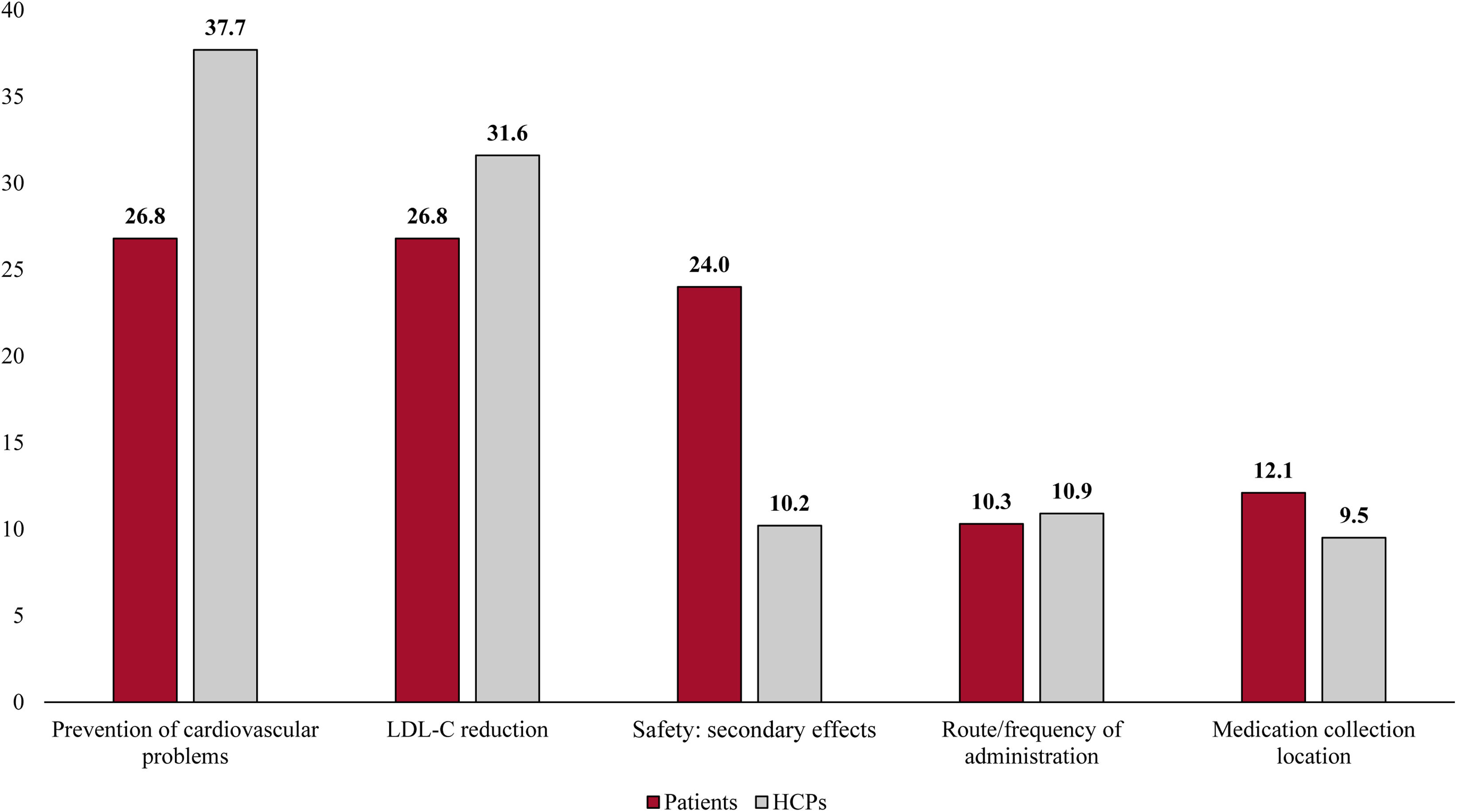

ResultsA total of 50 patients and 89 HCP participated. The estimated relative importance was: prevention of cardiovascular problems (HCP: 37.7%; patients: 26.8%); LDL-C reduction (HCP: 31.6%; patients: 26.8%); route and frequency of administration (HCP: 10.9%; patients: 10.3%) safety (HCP: 10.2%; patients: 24.0%); and medication collection location (HCP: 9.5%; patients: 12.1%). The preferred route and frequency of administration for HCP was a subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every 6 months, while patients equally preferred subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every 6 months and oral administration (r=0.01; P=.95) over a self-administered injection twice per month (r=−0.36; P=.01).

ConclusionsHCP and patients considered treatment efficacy preventing cardiovascular events and reducing LDL-C levels the most important attributes, followed by route and frequency of administration for HCP and safety for patients. Regarding route and frequency of administration, HCP preferred low frequency subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP and patients, are less prompt to accept a self-administered injection twice per month over the other options.

El control de los niveles de colesterol unido a lipoproteínas de baja densidad (cLDL) reduce el riesgo ateroesclerótico en pacientes con enfermedad cardiovascular ateroesclerótica. Sin embargo, no todos los tratamientos disponibles ofrecen la misma eficacia o seguridad, lo que influye en las preferencias de tratamiento. Nuestro estudio tuvo como objetivo identificar las preferencias de pacientes y profesionales sanitarios (PS) respecto a los atributos relacionados con los tratamientos hipolipemiantes (THL).

MétodosSe realizó una revisión de la literatura y 2 grupos focales (pacientes=4; PS=8) para identificar los atributos y niveles de las THL. Un total de 5 atributos con 2 o 3 niveles cada uno dieron lugar a 36 escenarios. La importancia relativa asignada a cada atributo se estimó mediante un modelo logit condicional.

ResultadosParticiparon un total de 50 pacientes y 89 PS. La importancia relativa estimada fue: prevención de problemas cardiovasculares (PS: 37,7%; pacientes: 26,8%); reducción de cLDL (PS: 31,6%; pacientes: 26,8%); vía y frecuencia de administración (PS: 10,9%; pacientes: 10,3%); seguridad (PS: 10,2%; pacientes: 24,0%); y lugar de recogida de la medicación (PS: 9,5%; pacientes: 12,1%). La vía y frecuencia de administración preferida por los PS fue la inyección subcutánea administrada por un profesional sanitario una vez cada 6 meses, mientras que los pacientes mostraron igual preferencia por la inyección subcutánea administrada por un profesional sanitario una vez cada 6 meses y la administración oral (r=0,01; p=0,95) frente a la inyección autoadministrada 2 veces al mes (r=−0,36; p=0,01).

ConclusionesLos PS y los pacientes consideraron que la eficacia del tratamiento en la prevención de eventos cardiovasculares y la reducción de los niveles de cLDL eran los atributos más importantes, seguidos por la vía y frecuencia de administración en el caso de los PS, y la seguridad en el caso de los pacientes. Con respecto a la vía y frecuencia de administración, los PS prefirieron la inyección subcutánea de baja frecuencia administrada por un profesional sanitario, mientras que los pacientes mostraron menor disposición a aceptar la inyección autoadministrada 2 veces al mes en comparación con las otras opciones.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 18.6 million deaths globally in 2019.1 In Spain, CVD are responsible for approximately 115000 deaths yearly, which represents 26.5% of total deaths.2 The major component of CVD is atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), which refers to coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral artery disease.3 In turn, patients with established ASCVD are considered to be at very high cardiovascular risk.4

Despite that multiple cardiovascular risk factors have been described,5,6 it has been demonstrated that elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) have a causal role in ASCVD.7,8 In this context, the scientific evidence available suggests that decreasing LDL-C should be a primary target in the treatment of dyslipidaemia.9 In fact, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS)4 recommend reducing LDL-C levels ≥ 50% from baseline, with a goal of < 55mg/dL (< 1.4mmol/L) for patients with very high cardiovascular risk.4

Despite the number of lipid-lowering therapies (LLT) available to meet this goal,10,11 most patients do not achieve the recommended LDL-C levels,12–14 which could be due to therapeutic inertia, lack of perceived risk, or low patient adherence to treatment, among other causes.14–16

In patient-centred care, patients and clinicians discuss the best therapeutic option with patients’ preferences and concerns in mind. This shared-decision making process has demonstrated a better conflict resolution, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes.17 However, therapeutic decision-making has become a more complex process, especially in multidisciplinary teams.

In this context, preference studies are of relevance as they allow to gather information on the value that participants assign to different attributes of a given medical intervention.18 The most commonly used method to study patients’ and healthcare professionals’ (HCP) health preferences is the discrete choice experiment (DCE), in which participants are asked to choose between 2 or more alternatives (scenarios) where at least one attribute is systematically varied.19,20

Studies aiming at assessing patients’ and HCP preferences in the field of ASCVD LLT are scarce. Thus, considering all the above, the main goal of this study was to identify the preferences of patients with very high cardiovascular risk and HCP for the attributes related to LLT in Spain. We also aimed to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients and HCP and to evaluate the association between patients’ preferences and their adherence to treatment.

MethodsStudy designThis was an observational, cross-sectional, non-interventional study based on a DCE, directed to patients with very high cardiovascular risk and established ASCVD and HCP. The study was carried out between April 2022 and May 2023, and was coordinated by 2 cardiologists with recognized expertise in lipid research. The study was conducted as part of a research collaboration with Novartis; however, coordination and oversight were carried out independently by the Research Agency of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Arnau de Vilanova Hospital in Valencia and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients who accepted the conditions of the study gave their consent to participate in the study.

Study participantsThe study population included patients with established ASCVD and HCP attending to this profile of patients at the time of the study. Patients were invited to participate by the patients’ association Cardioalianza. Those professionals who participated in the focus groups to identify the attributes for the DCE did not take part in the subsequent preference study, to minimize potential bias. HCP selection for the preference study was based on ensuring a balanced representation of the key specialties involved in the management of ASCDV. Accordingly, the final sample included 89 HCP: 15 experts from cardiology, neurology, primary care, nursing, and pharmacy, and 14 from internal medicine. Invitations to participate were distributed by the Spanish Society of Cardiology to HCP, via an email containing the basic information of the study and the URL link to the electronic case report form. Only those participants who agreed to participate could complete the case report form.

Patients of 18 years of age or older, with established ASCVD in the past 2 years were included in the study. Patients with Alzheimer's disease or other type of dementia, advanced or metastatic cancer, or with comprehension and/or reading difficulties or any condition that made it not possible to complete the preferences exercise and answer the study questions were excluded. HCP from the mentioned specialties currently working in hospitals, primary care centres, and community pharmacies attending patients with established ASCVD were included in the study.

Discrete choice experimentIn DCE, participants choose between 2 hypothetical treatment alternatives described by attributes (treatment characteristics) and levels (values of the attributes).20

The DCE was carried out in 2 phases: (a) establishment of the scenarios and (b) preference study (Fig. 1 of the supplementary data).

In the first phase, attributes and levels were selected to obtain the scenarios subsequently used in the preference study. Phase I consisted of (a) a targeted literature review to identify potential attributes and levels (2 or 3 per attribute) characterising LLT and their effects and (b) 2 focus groups, one with patients (n=4) and one with HCP (n=8), to review and validate the proposed attributes and levels. The identified attributes (safety and adverse events, follow-up, monitorization and visits frequency, medication collection location, LDL-C reduction, prevention of cardiovascular problems, atherosclerotic load/accumulation of plaques in the arteries, frequency of administration, and route of administration) were presented to both patients and HCP focus group, the latter composed of 2 cardiologists, one neurologist, 2 internal medicine clinicians, one nurse, one primary care physician, and one pharmacist. HCP selected the 5 most relevant attributes for a LLT. An orthogonal and balanced design was applied to eliminate extreme response bias.

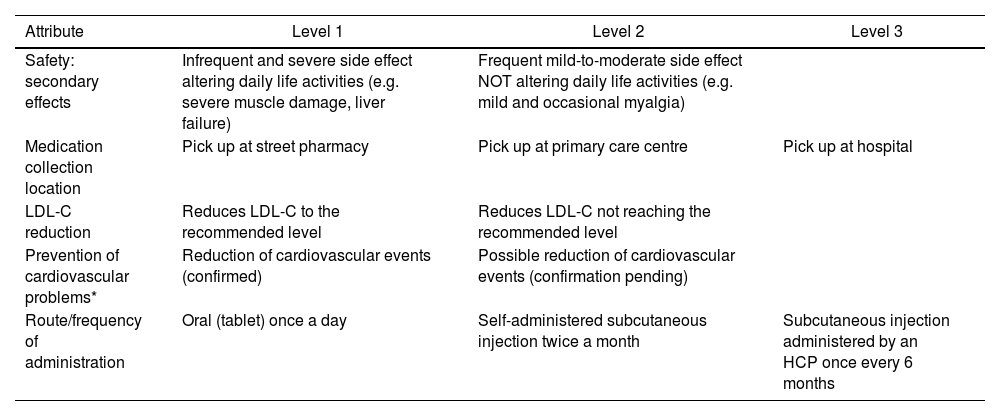

As a result of the literature review and the 2 focus groups, 5 attributes with 2 or 3 levels each were selected, resulting in 36 scenarios (Table 1).

Attributes and levels used in the DCE.

| Attribute | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety: secondary effects | Infrequent and severe side effect altering daily life activities (e.g. severe muscle damage, liver failure) | Frequent mild-to-moderate side effect NOT altering daily life activities (e.g. mild and occasional myalgia) | |

| Medication collection location | Pick up at street pharmacy | Pick up at primary care centre | Pick up at hospital |

| LDL-C reduction | Reduces LDL-C to the recommended level | Reduces LDL-C not reaching the recommended level | |

| Prevention of cardiovascular problems* | Reduction of cardiovascular events (confirmed) | Possible reduction of cardiovascular events (confirmation pending) | |

| Route/frequency of administration | Oral (tablet) once a day | Self-administered subcutaneous injection twice a month | Subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every 6 months |

DCE, discrete choice experiment; HCP, healthcare professionals; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

In phase II, participants were presented with all scenarios in pairs and asked to determine their preferences for each attribute and level. Prior to their preference selection, patients were presented with a brief description of each attribute and level defining each hypothetical LLT.

Real medications or therapies were not evaluated in this study. The scenarios reflected hypothetical treatments, regardless of their actual viability.

Study variablesPatients provided sociodemographic (age, sex, academic education level, employment situation) and clinical characteristics (disease evolution time, history of ASCVD, LLT, LDL-C levels) and evaluated their adherence to the treatment using the 4-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-4),21 which consists of 4 dichotomous response items (yes or no). Treatment adherence was classified as high (“no” in all 4 items), medium (“no” in 2–3 items), and low (“no” in 0–1 items).

HCP completed a questionnaire on sociodemographic (sex) and professional characteristics (professional experience, specialty, other professional activity).

Both groups determined their preferences regarding the attributes related to LLT.

Statistical analysisCentrality (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation [SD]) measures were calculated for continuous variables. Numbers and percentage were used to describe categorical variables.

The relative importance (RI) given to each attribute was estimated using a conditional logit model, which considers that the choice depends on the characteristics shown, omitting heterogeneity between individuals. However, it allows estimators or partial utility values to be obtained.

To analyse the association between treatment adherence and LDL-C control in patients and how patients and HCP sociodemographic and clinical characteristics might influence on their preferences Student's t test, ANOVA, or Chi-square tests were used. Preliminary analyses were carried out to ensure compliance with the statistical assumptions of normality. In the case that these assumptions were not met, the equivalent non-parametric Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used.

The sample size was estimated based on the approach proposed by Orme,22 (nta)/c ≥500, where n is the number of respondents, t is the number of tasks (t=36) a is the number of alternatives per task and c is the largest number of levels for any attribute. Assuming approximately 36 choice tasks per participant with 2 choice alternatives and a maximum of 3 levels per attribute, the minimum sample size was estimated at 21 responded DCE, which required a minimum of 42 participants for each group (patients and HCP) as each participant had to respond half of the questions.

All statistical analyses were done using SAS Enterprise Guide V7.15. All values of P<.05 were considered statistically significant for all statistical tests.

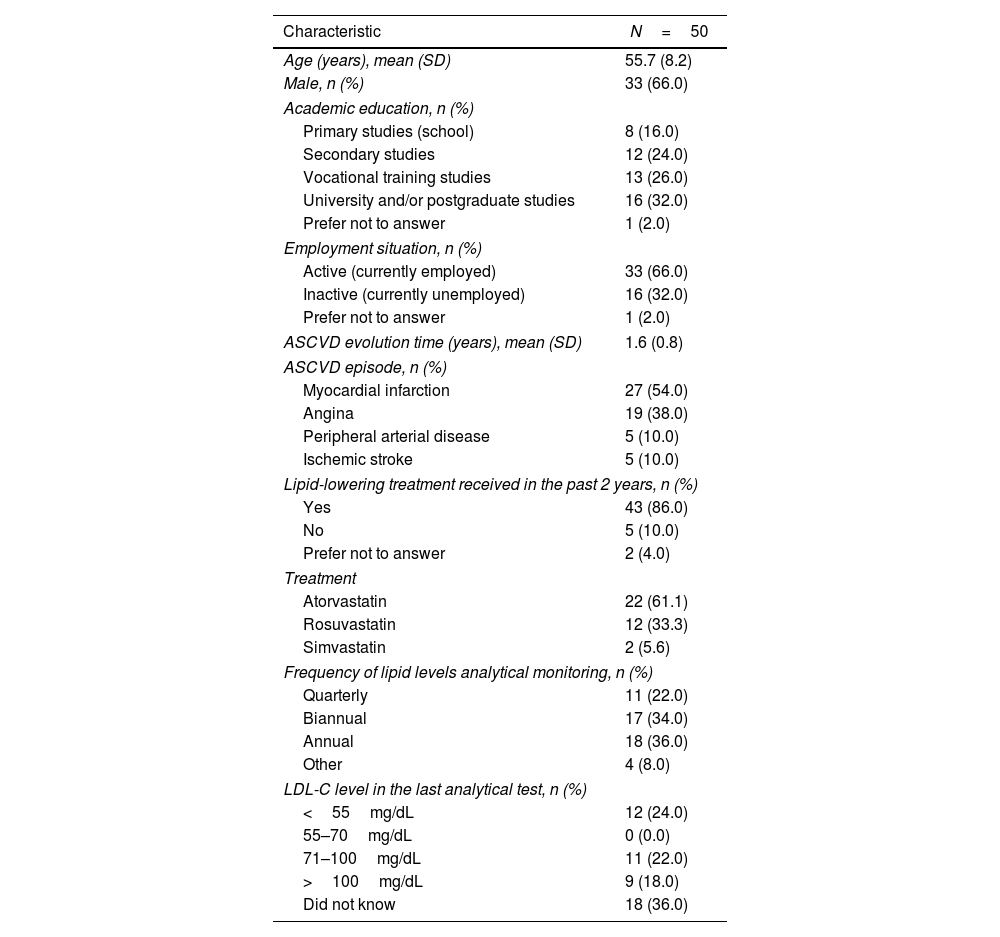

ResultsParticipants sociodemographic characteristicsA total of 50 patients participated in the study. Most of them (66%) were men and had a mean age of 55.7 years. Almost all patients (98%) had, at least, primary studies (school), and most (66%) were employed at the moment of the study (Table 2). Approximately half of the patients (54%) had suffered a myocardial infarction, the most common LLT received was atorvastatin (61%), and 36.0% of patients did not know their LDL-C levels (Table 2).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients participating in the study.

| Characteristic | N=50 |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 55.7 (8.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 33 (66.0) |

| Academic education, n (%) | |

| Primary studies (school) | 8 (16.0) |

| Secondary studies | 12 (24.0) |

| Vocational training studies | 13 (26.0) |

| University and/or postgraduate studies | 16 (32.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.0) |

| Employment situation, n (%) | |

| Active (currently employed) | 33 (66.0) |

| Inactive (currently unemployed) | 16 (32.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.0) |

| ASCVD evolution time (years), mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.8) |

| ASCVD episode, n (%) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 27 (54.0) |

| Angina | 19 (38.0) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 5 (10.0) |

| Ischemic stroke | 5 (10.0) |

| Lipid-lowering treatment received in the past 2 years, n (%) | |

| Yes | 43 (86.0) |

| No | 5 (10.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (4.0) |

| Treatment | |

| Atorvastatin | 22 (61.1) |

| Rosuvastatin | 12 (33.3) |

| Simvastatin | 2 (5.6) |

| Frequency of lipid levels analytical monitoring, n (%) | |

| Quarterly | 11 (22.0) |

| Biannual | 17 (34.0) |

| Annual | 18 (36.0) |

| Other | 4 (8.0) |

| LDL-C level in the last analytical test, n (%) | |

| <55mg/dL | 12 (24.0) |

| 55–70mg/dL | 0 (0.0) |

| 71–100mg/dL | 11 (22.0) |

| >100mg/dL | 9 (18.0) |

| Did not know | 18 (36.0) |

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SD, standard deviation.

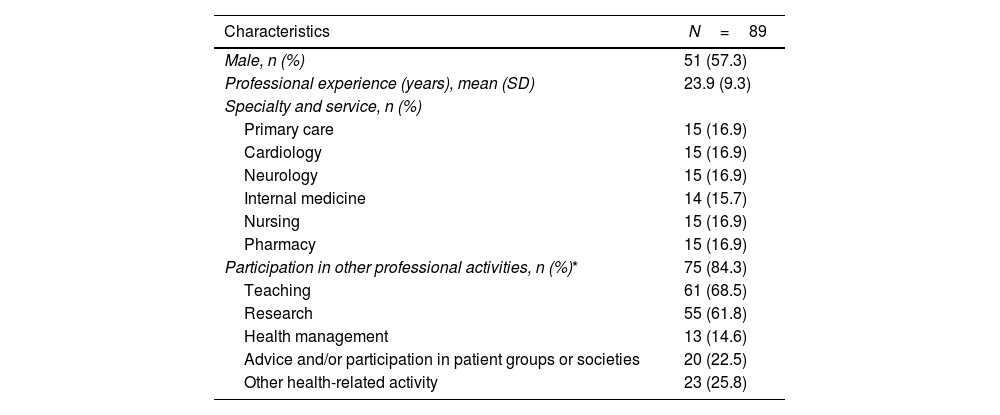

On the other hand, 89 HCP, 57% of them men, with a mean of 23.9 years of experience participated in the study. Most HCP participated also in other professional activities (84%) (Table 3).

Sociodemographic and professional characteristics of HCP participating in the study.

| Characteristics | N=89 |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 51 (57.3) |

| Professional experience (years), mean (SD) | 23.9 (9.3) |

| Specialty and service, n (%) | |

| Primary care | 15 (16.9) |

| Cardiology | 15 (16.9) |

| Neurology | 15 (16.9) |

| Internal medicine | 14 (15.7) |

| Nursing | 15 (16.9) |

| Pharmacy | 15 (16.9) |

| Participation in other professional activities, n (%)* | 75 (84.3) |

| Teaching | 61 (68.5) |

| Research | 55 (61.8) |

| Health management | 13 (14.6) |

| Advice and/or participation in patient groups or societies | 20 (22.5) |

| Other health-related activity | 23 (25.8) |

HCP, healthcare professionals; SD: standard deviation.

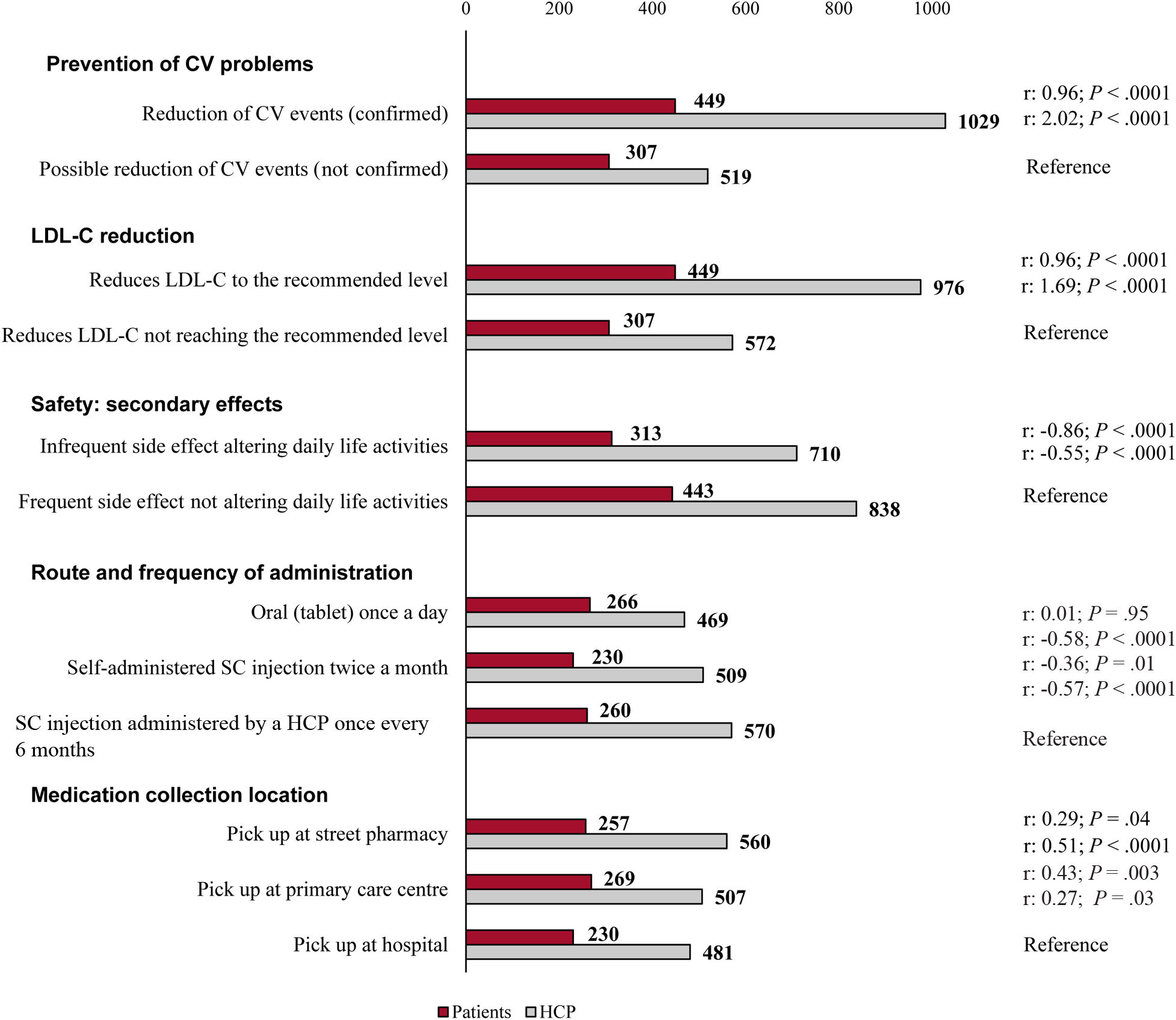

The logistic regression analysis showed that patients’ main preferences were a treatment that could be able to reduce cardiovascular events (parameter estimate [r]=0.96, P<.0001) and LDL-C to the recommended levels (r=0.96, P<.0001), followed by having frequent side effects not altering their daily life activities (reference, P<.0001), and being able to collect the medication at the primary care centre (r=0.43, P=.003) (Fig. 1). Additionally, patients equally preferred subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every 6 months and oral administration (r=0.01; P=.95) over a self-administered injection twice per month (r=−0.36; P=.01) (Fig. 1).

Similarly, HCP preferred a treatment able to reduce cardiovascular events (r=2.02, P<.0001) and LDL-C to the recommended levels (r=1.69, P<.0001), followed by having frequent side effects not altering their daily life activities (reference, P<.0001), and preferred a route of administration consisting of a subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every 6 months (Fig. 1).

Further analyses on patients’ preferences, according to their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, did not show statistically significant differences regarding their sociodemographic profile, years from ASCVD diagnosis, and prior history of ASCVD (angina, peripheral arterial disease, ictus, and myocardial infarction). However, patients showed statistically significant differences regarding the route of administration according to the LLT received (high vs medium: P=.001; atorvastatin vs rosuvastatin vs simvastatin: P=.002; Table 1 of the supplementary data).

For HCP, no further differences were observed according to their years of experience and their sociodemographic and professional profile (Table 2 of the supplementary data).

The results of the logistic regression analysis combined with participants sociodemographic characteristics showed similar results for patients’ and HCP treatment preferences. None of the sociodemographic (age, sex, academic education level, employment situation; all P>.05) characteristics were statistically significant (Tables 2–5 of the supplementary data).

Relative importanceFor patients, the most important attributes related to LLT were the prevention of cardiovascular events (RI: 26.8%) and LDL-C reduction (RI: 26.8%), followed by treatment safety (RI: 24.0%) (Fig. 2). For HCP, the most important attribute was prevention of cardiovascular events (RI: 37.7%), followed by LDL-C reduction (RI: 31.6%). However, they considered that the route and frequency of administration (RI: 10.9%) was more important than treatment safety (RI: 10.2%) (Fig. 2).

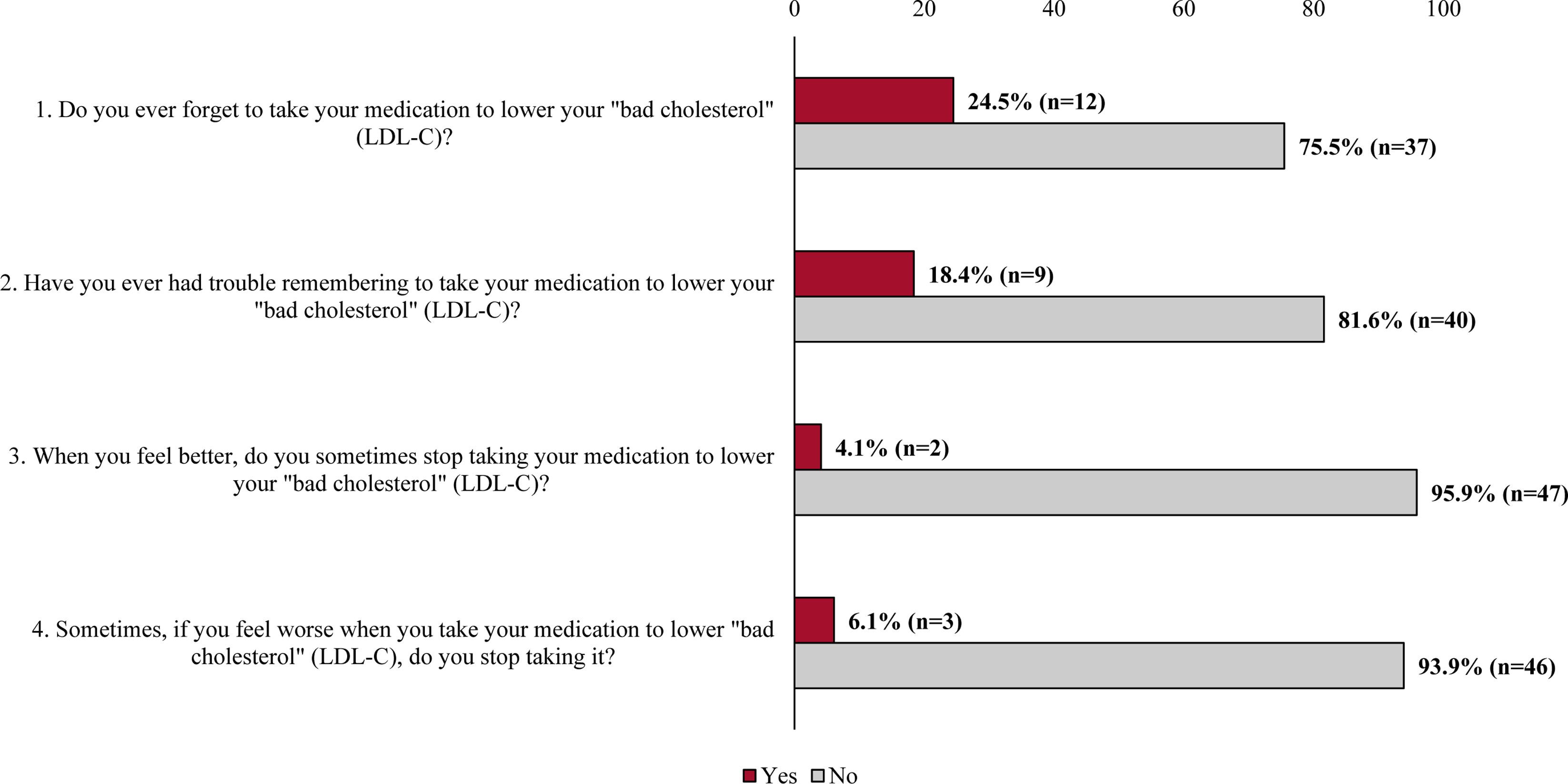

Treatment adherenceAll patients, except 1, responded the MMAS-4 questionnaire (Fig. 3), resulting in 63.3% of patients showing high adherence to treatment and 34.7% of patients with medium adherence. Only 1 patient (2.0%) showed low adherence to treatment.

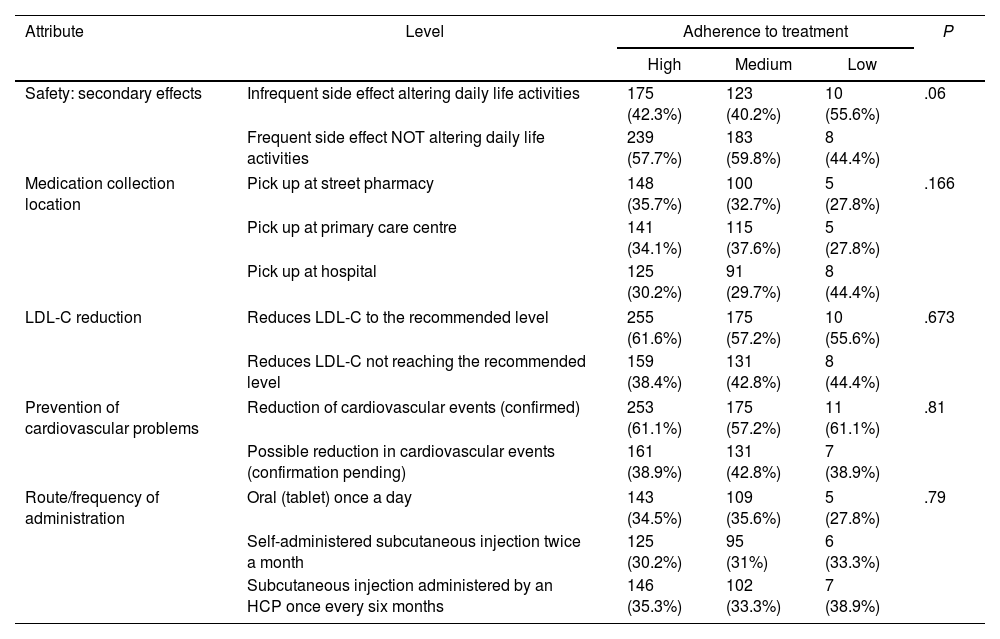

The analysis of patients’ preferences considering their adherence to treatment showed that there were no significant differences between patients for any of the adherence groups and any of the attributes (Table 4).

Association between patients’ preferences and their declared adherence to treatment.

| Attribute | Level | Adherence to treatment | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | |||

| Safety: secondary effects | Infrequent side effect altering daily life activities | 175 (42.3%) | 123 (40.2%) | 10 (55.6%) | .06 |

| Frequent side effect NOT altering daily life activities | 239 (57.7%) | 183 (59.8%) | 8 (44.4%) | ||

| Medication collection location | Pick up at street pharmacy | 148 (35.7%) | 100 (32.7%) | 5 (27.8%) | .166 |

| Pick up at primary care centre | 141 (34.1%) | 115 (37.6%) | 5 (27.8%) | ||

| Pick up at hospital | 125 (30.2%) | 91 (29.7%) | 8 (44.4%) | ||

| LDL-C reduction | Reduces LDL-C to the recommended level | 255 (61.6%) | 175 (57.2%) | 10 (55.6%) | .673 |

| Reduces LDL-C not reaching the recommended level | 159 (38.4%) | 131 (42.8%) | 8 (44.4%) | ||

| Prevention of cardiovascular problems | Reduction of cardiovascular events (confirmed) | 253 (61.1%) | 175 (57.2%) | 11 (61.1%) | .81 |

| Possible reduction in cardiovascular events (confirmation pending) | 161 (38.9%) | 131 (42.8%) | 7 (38.9%) | ||

| Route/frequency of administration | Oral (tablet) once a day | 143 (34.5%) | 109 (35.6%) | 5 (27.8%) | .79 |

| Self-administered subcutaneous injection twice a month | 125 (30.2%) | 95 (31%) | 6 (33.3%) | ||

| Subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every six months | 146 (35.3%) | 102 (33.3%) | 7 (38.9%) | ||

HCP, healthcare professional; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

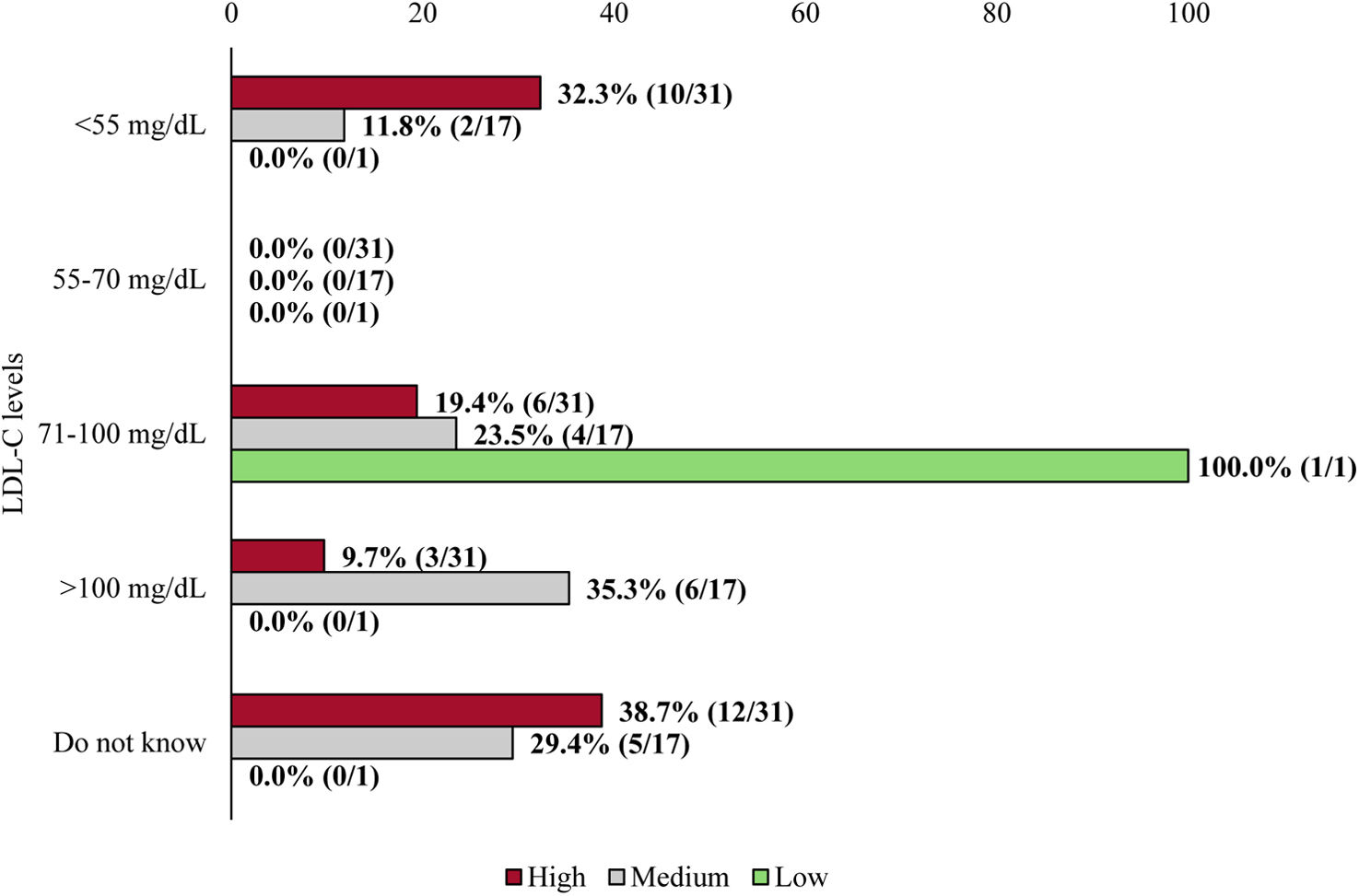

On the other hand, patients with lower LDL-C levels showed a higher adherence to treatment however, the observed differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 4).

Association between patients’ LDL-C levels and their declared adherence to treatment. The number of patients describing their level of adherence is defined according to each LDL-C level range. Percentages were calculated by considering the total number of patients for each level of adherence (41 patients with high adherence, 17 with medium adherence, and 1 with low adherence). LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

The results obtained in our study regarding treatment preferences were similar for patients and HCP, as both preferred a treatment able to reduce cardiovascular events and LDL-C to the recommended levels. Similar results were also reported by a recent publication evaluating the adherence of physicians to ESC/EAS guidelines, with most of the participants selecting reducing LDL-C levels followed by cardiovascular risk reduction as the primary target of a LLT.13 Although direct comparisons with our results cannot be established, the results of this study emphasize that reduction of cardiovascular risk and LDL-C levels are the 2 most important attributes of a LLT for HCP when selecting the most appropriate therapy. This is likely due to the established association of LDL-C reduction and the reduction in the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events.4,23,24

Regarding the estimated RI for each attribute, patients considered prevention of cardiovascular problems (26.8%), LDL-C reduction (26.8%), and treatment safety (24.0%) almost equally important. HCP equally had a strong preference for the prevention of cardiovascular problems (estimated RI: 37.7%) and LDL-C reduction (estimated RI: 31.6%). However, noteworthy discrepancies were observed between HCP and patients concerning the third most important attribute. While HCP identified route and frequency of administration as the third priority (10.9%), patients placed greater importance on safety. This difference could be explained as given the HCP experience managing LLT, where safety represent no longer a concern for them, and low treatment adherence is a major issue for LLT. Patients prioritization of treatment safety might be probably due to the different perceptions patients have about health status or medication compared with HCP25 or the uncertainty some patients have about the safety of LLT such as statins.26 Similar discrepancies regarding treatment preferences between patients and HCP have been already described in several fields,27,28 with patients giving more importance to risk and side effects than HCP.29 A review on this matter reported that HCP consider more important those attributes related to structure and outcomes care than patients.30 Our results are in line with these findings; HCP estimated a higher RI for the efficacy attributes, while treatment safety was more important for patients than for HCP.

One of the main findings of our study is the difference observed in the preferred route and frequency of administration. HCP preferred a subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every 6 months to oral treatment, probably as it ensures treatment effect for those 6 months. Additionally, HCP administering the treatment twice per year could reinforce to patients the importance of being compliant with therapies, resulting in an improved adherence and persistence to other LLTs. Thus, representing an opportunity for overcoming the challenge of a low adherence rate to LLT.31,32 In this regard, a previous study showed that patients adherent to a low-intensity LLT presented lower risk of cardiovascular events compared with nonadherent patients receiving a high-intensity LLT.33 The mentioned route is also significantly preferred over a self-administered injection twice per month. The results reported by HCP are slightly different from those obtained for patients, who equally preferred a subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every 6 months and an oral daily treatment over a self-administered injection twice per month. This suggests that patients prioritize comfort of the administration, understood as oral administration or an injection as widely spaced in time as possible, a preference that has also been documented in previous studies conducted in other disease areas.34,35

On the other hand, patients preferred to collect the medication in their primary care centre, followed by the street pharmacy, while HCP preferred that patients collected the medication at the street pharmacy in first place, followed by the primary care centre. Both considered collecting the medication at the hospital as the least preferred option. This could be explained as HCP might consider that collecting the medication at the usual street pharmacy could increase the adherence to the treatment, while patients, especially older patients, could feel more confident collecting it from their trusted primary care physician. In this regard, it could be hypothesised that the option of collecting the medication at a primary care centre was the least preferred by HCP, as this could increase the already high workload of primary care.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that, overall, we did not find statistically significant differences in patients’ and HCP preferences regarding their sociodemographic or clinical variables. However, we cannot rule out that patients LDL-C levels could influence their preferences as approximately a third of them did not report these data. In addition, no statistically significant differences were observed regarding patients’ adherence to treatment. However, it should be noted that information on adherence was provided by participating patients and their responses could have been influenced by the effect of memory.

For physicians, understanding patients’ perceptions and preferences might help during the treatment shared decision-making process.27,30 Thus, we believe that the study provides added value by considering patients’ preferences, which are key to this process. In addition, the information obtained in the present study can help better understand the strategies that could be implemented to improve patient-HCP relationship and collaboration in the management of patients with established ASCVD.

This study has some limitations. All estimated preferences and RI depended on the attributes and levels selected to define the scenarios, which were related to the available treatments and their effects and the pathologies they cover. Thus, other attributes such as treatment costs were not considered. The inclusion of other criteria that placed more emphasis on variables perceived by patients (e.g. quality of life, satisfaction) could potentially offer other more striking results and differences between patients and HCP. The sample size was not large enough to show differences between subgroups. These results should be taken as a first approximation to the estimation of these preferences and therefore, further studies are necessary to expand these results. On the other hand, it is possible that participating patients were better informed than the general population, as they were recruited by a patients’ association. This factor might also account for the high adherence observed, given that such individuals are likely to be more aware of their condition and committed to strict treatment compliance. Despite the stated limitations, a high number of patients and experienced HCP from 6 different specialties participated in the study, being representative of the situation of the management of LLT in patients with established ASCVD.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, treatment efficacy preventing cardiovascular events and reducing LDL-C levels were the most important attributes for HCP and patients. Furthermore, HCP showed their preference for a subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP once every 6 months to a self-administered treatment while patients equally preferred oral or a subcutaneous injection administered by HCP once every 6 months over a self-administered injection twice a month. Patients valued treatment safety, preferring frequent side effects not altering their daily life activities. Overall, the results of the present study can contribute to improve decision-making in the management of ASCVD.

- -

Both patient and HCP practices and behaviour can influence the effectiveness of LLT.

- -

Discrete choice experiment allows for the collection of valuable insights from both patients and HCP regarding a specific intervention.

- -

This study has revealed that preferences in treatment administration and frequency vary between HCP and patients. HCP preferred a subcutaneous injection administered by an HCP every 6 months over a self-administered treatment. Patients equally preferred oral administration or a subcutaneous injection administered by HCP once every 6 months over a self-administered injection twice a month.

- -

Given that patient and HCP practices influence the efficacy of LLT, the results of this study highlight the preferences of the main stakeholders in the treatment process, which helps deepen the understanding of patient realities.

This study of the Research Agency of the Spanish Cardiology Society was funded by Novartis.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Arnau de Vilanova Hospital in Valencia and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients who accepted the conditions of the study gave their consent to participate in the study. A cross-sectional, non-interventional design was employed for analysis and consecutive sampling was carried out on 33 males and 17 females. A total of 89 HCP participated in the study, 51 males and 38 females.

Statement on the use of artificial intelligenceNo artificial intelligence was employed.

Authors’ contributionsR. Fernández Olmo, J. Parrondo, L. Martín Mitjana, S. Reimondez-Troitiño, and J. Cosín-Sales: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, original draft writing, review and editing.. A.B. Álvarez Hermida, M. Castellanos Rodrigo, J.F. Gómez Cerezo, M.J. Igual Guaita, S.J. Jansen Chaparro, and J.C. Obaya Rebollar: investigation, writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of interestR. Fernández Olmo has received honoraria from Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Servier. M. Castellanos Rodrigo has received honoraria as a speaker from Ferrer, Daiichi-Sankyo and BMS-Pfizer, and has participated in advisory services for BMS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis, and Pfizer. J.F. Gómez Cerezo has received fees as a speaker from Amgen SA, Daiichi-Sankyo, Menarini, Novartis, and Sanofi. M.J. Igual Guaita has received honoraria for advisory services from Novartis. S.J. Jansen Chaparro has received honoraria as a speaker and for advisory services from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ferrer, and Sanofi-Aventis. J.C. Obaya Rebollar has received fees as a speaker from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Esteve, Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. J. Cosín-Sales has received conference fees from Almirall, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ferrer, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Organon, Rovi, and Sanofi; has participated in advisory services for Almirall, Amgen, MSD, Novartis, and Sanofi; and has received research grants from Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ferrer, MSD, and Sanofi. J. Parrondo, L. Martín Mitjana, and S. Reimóndez-Troitiño are employees at Novartis. A.B. Álvarez Hermida has nothing to declare.

Data availabilityData are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request complying with the corresponding data protection laws.

The authors would like to thank Víctor Latorre and Daniel Pinto, PhD at Outcomes ‘10 for medical writing support.