Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been outlined as a possible risk factor for poorer outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

MethodsA meta-analysis was performed with currently available studies that report the prevalence of CVD in survivors vs non-survivors in patients with COVID-19 using reports available at 16 July 2020. Analyses were performed by a random effects model and sensitivity analyses were performed for the identification of potential sources of heterogeneity or to assess the small-study effects.

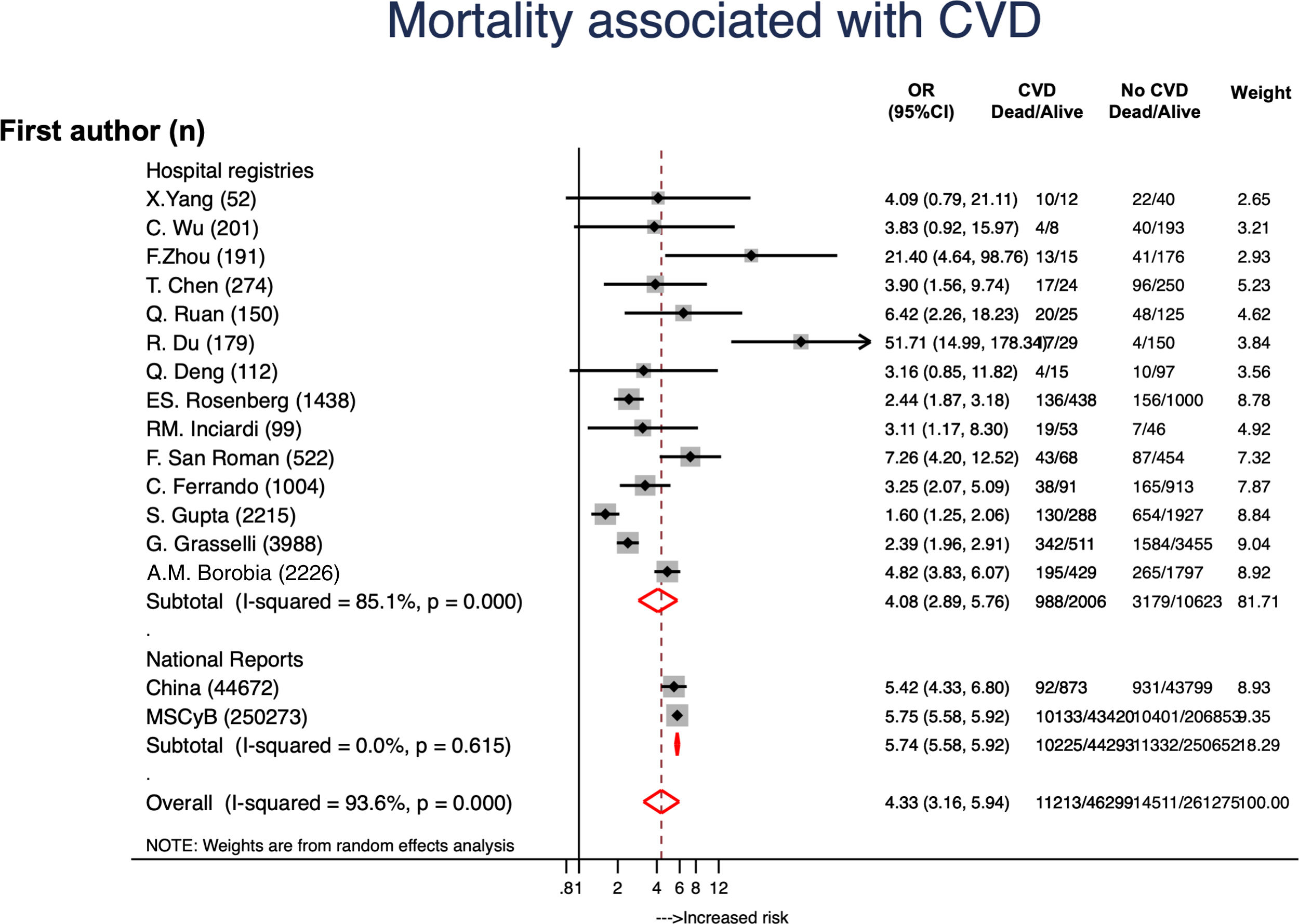

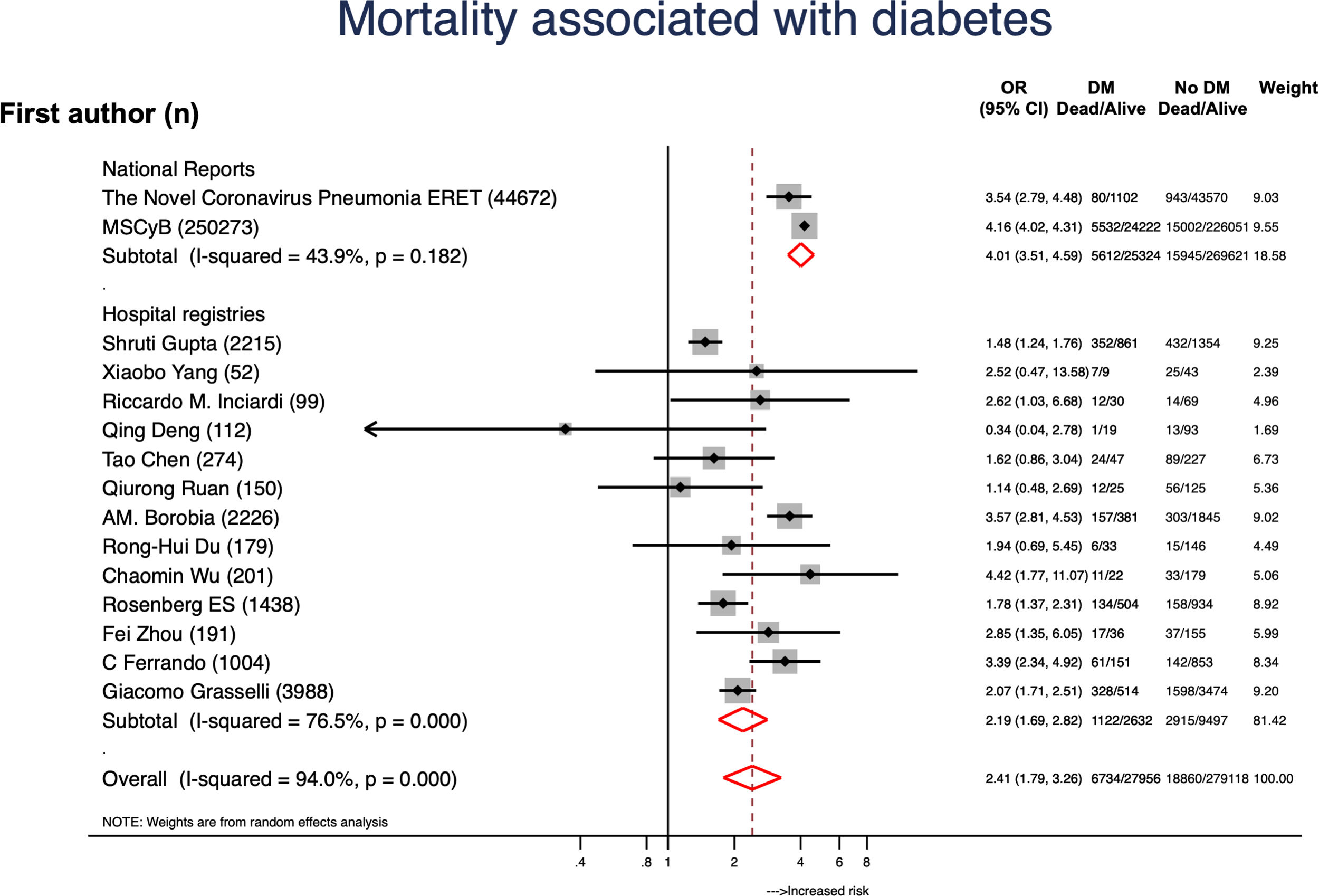

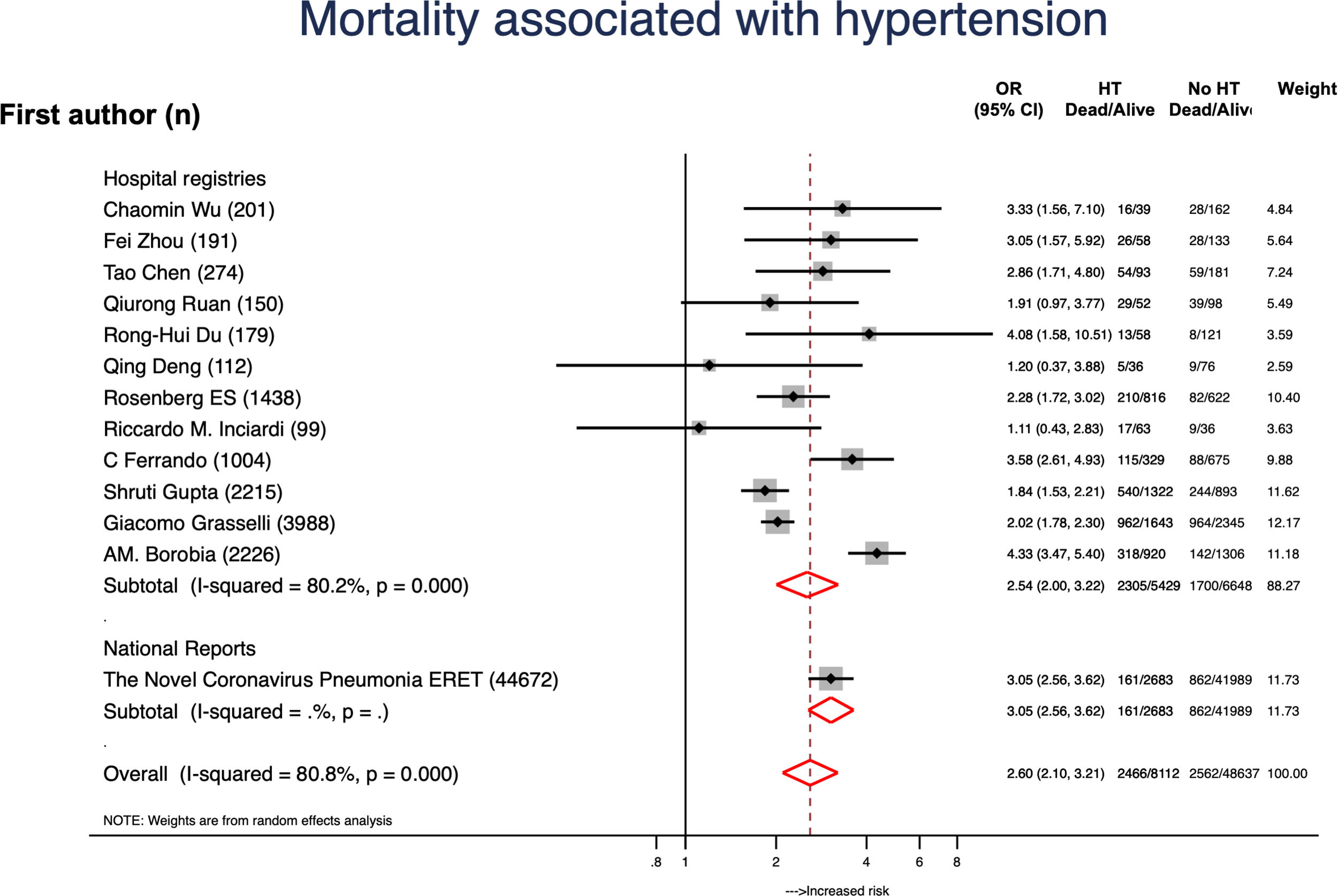

ResultsA total of 307596 patients from 16 reports were included and 46321 (15.1%) had CVD. Globally, mortality rate was 8.2% (20534 patients) and mortality rates were higher in hospital registries (48.7%) compared to national reports (23.1%). A total of 11213 (24.2%) patients with CVD died and mortality rates were also higher in hospital registries (48.7%) compared to national reports (23.1%). CVD was associated to a 4-fold higher risk of mortality (OR, 4.33; 95%CI, 3.16–5.94). Data from 28048 patients with diabetes was available. Diabetes was associated to higher mortality risk (OR, 2.41; 95%CI, 1.79–3.26; P<.001). From 40173 subjects with hypertension it was concluded that hypertension was also a risk factor for higher mortality (OR, 2.60; 95%CI, 2.10–3.21; P<.001).

ConclusionsPatients with CVD and COVID-19 have a 4-fold higher risk of death. Diabetes and hypertension are also associated with higher mortality risk.

Las enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) se han identificado como un factor de riesgo de mal pronóstico en los pacientes con COVID-19.

MétodosSe realizó un metanálisis de estudios actualmente disponibles con la prevalencia de ECV en supervivientes frente a no supervivientes en pacientes con COVID-19 hasta el 16 de julio de 2020. Los análisis se realizaron mediante un modelo de efectos aleatorios y sensibilidad. Se realizaron análisis para identificar posibles fuentes de heterogeneidad o evaluar los efectos de los estudios pequeños.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 307.596 pacientes de 16 estudios, de los que 46.321 (15,1%) tenían ECV. La tasa de mortalidad fue del 8,2% (20.534 pacientes) y fue superior en los registros hospitalarios (48,7%) en comparación con los informes nacionales (23,1%). Un total de 11.213 (24,2%) pacientes con ECV fallecieron y las tasas de mortalidad también fueron más altas en los registros hospitalarios (48,7%) en comparación con los informes nacionales (23,1%). La ECV se asoció con un riesgo de mortalidad 4 veces mayor (OR; 4,33; IC 95%: 3,16-5,94). Se disponía de datos de 28.048 pacientes con diabetes que también se asoció a un mayor riesgo de mortalidad (OR: 2,41; IC 95%: 1,79-3,26; p<0,001). De 40.173 pacientes con hipertensión, también se concluyó que era un factor de riesgo de mayor mortalidad (OR: 2,60; IC 95%: 2,10-3,21; p<0,001).

ConclusionesLos pacientes con ECV y COVID-19 tienen un riesgo 4 veces mayor de muerte. La diabetes y la hipertensión arterial también son factores de mayor riesgo en los pacientes con COVID-19.

After the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in China, the coronavirus desease 2019 (COVID-19), and its worldwide spread, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared its incidence as pandemic in February 2020.1 The lack of reliable information lead to early and worthy reports of clinical features2,3 and mortality rates.4–7 Most initial clinical data came from hospital registries and, therefore, reflected the in-hospital course and mortality of patients with COVID-19 infection.8 By the end of April, the pandemic had widely affected Europe and more than 50000 patients had died.9,10

Although most patients with COVID-19 infection develop mild symptoms, a relevant percentage that can be from 15 to 20%, develop pulmonary insufficiency and systemic symptoms that require hospitalization or intensive care treatments.2,3,11–14 To elucidate what are the risk factors for severe illness or death remains a clinical challenge.15–17 Patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) are at increased risk of infections and have higher mortality rates for infectious diseases.18 Comorbidities, and specially age or CVD, have been outlined as a risk factor for poorer outcomes in COVID-19 patients from the first reports4–7,19 and also in european cohorts.20 In collaboration with the National Health Commission of China a risk score to predict severe COVID-19 disease that includes CVD as one of the qualifying comorbidities has recently been developed and validated.21 Our study aimed to describe and define the risk of patients with CVD and COVID-19 infection.

2MethodsWe performed a meta-analysis in line with recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement22 (Table 1 of the supplementary data). We carried out a systematic search (using PUBMED, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [CENTRAL], and Google Scholar), without language restriction, for papers using the Medical Subject Headings terms “Coronavirus,” “COVID-19”, “Mortality, “Clinical outcomes” and “Clinical course” up to 25 July 2020. We also reviewed all institutional websites to obtain national reports of coronavirus. The primary outcome was all-cause death. As a result 16 studies that reported clinical features of patients who died vs survivors were identified: 16 were hospital registries4–7,17,19,20,23–31 and 2 were national reports (one from China32 and other from Spain.10) A total of two hospital registries were not included in the metanalysis, one hospital registry included only patients with CVD,7 and it was not included in the analysis. The study by Mehra et al.17 was excluded since results were withdrawn from the journal. National reports from Italy,33 Germany,34 UK,35 Belgium36 and France37 did not report the prevalence of CVD in patients who died from COVID. Therefore, analyses were performed using 16 reports (2 national reports and 14 hospital registries). CVD included coronary heart disease, heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease. For the eligible studies, two authors independently abstracted data into a standardized form; discrepancies in data extraction and quality assessment were resolved by discussion or consensus with a third author.

2.1Statistical analysisClinical features and in-hospital mortality were available in all studies. Relative risk reductions and percentage of incidences were used. The study-specific standard errors for the estimated relative risks were used to model the within-study variation. The percentage of variability across studies attributable to heterogeneity beyond chance was estimated using the I2 statistic. Once heterogeneity was observed and assuming that the study effect sizes were different and that the collected studies represented a random sample from a larger population, all the analyses were performed by a random effects model. Sensitivity analyses were performed for the identification of potential sources of heterogeneity between trials with meta-regression analyses and Harbord test, to assess the small-study effects.33 All analyses were performed using STATA 14.3 (StataCorp. 2009. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) software.

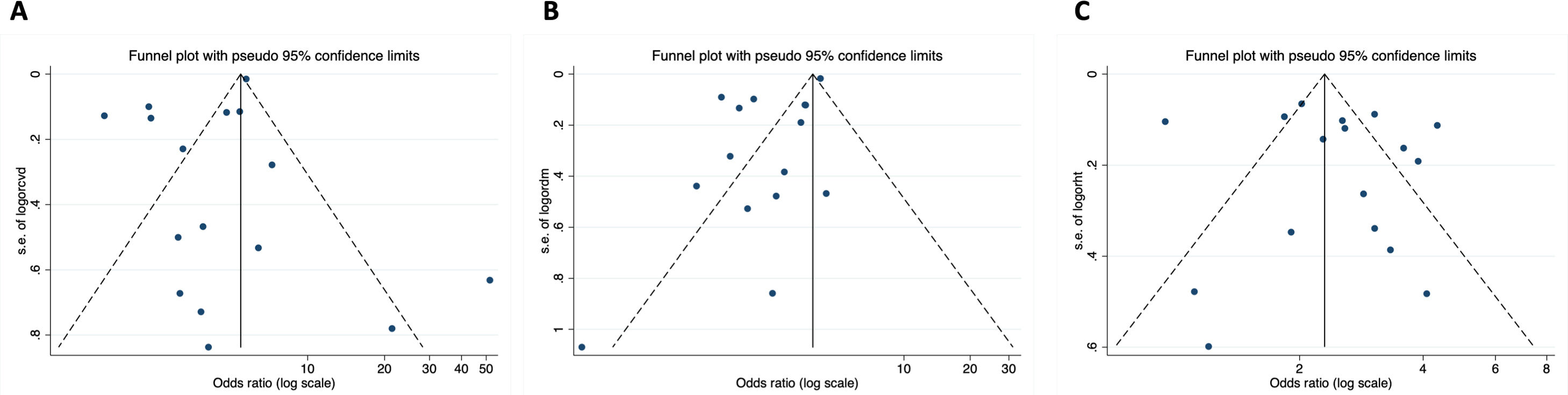

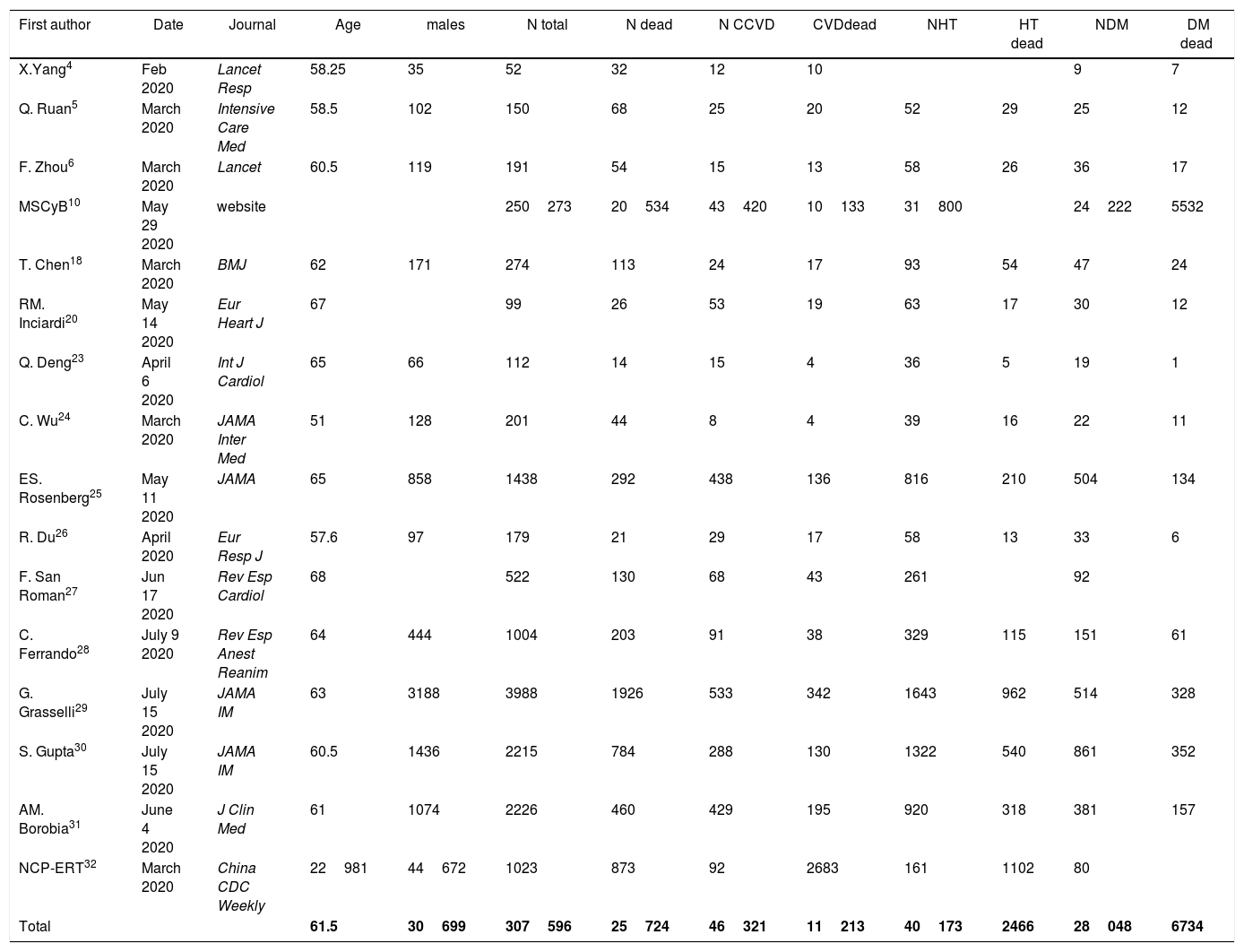

3ResultsA total 307596 patients from 16 reports were included and 46321 (15.1%) had CVD (Table 1). Mean age was 61.6 (4.3) and 42.5% were males. A total of 25724 (8.4%) patients died; mortality rates were higher in hospital registries (48.3%; 1926/3988) compared to national reports (8.2%; 20534/250273). A total of 11213 (24.2%) patients with CVD died and mortality rates were also higher in hospital registries (48.7%; 988/2028) compared to national reports (23.1%; 10225/44293). CVD was associated to 4-fold higher risk of mortality (OR, 4.33; 95%CI, 3.16–5.94) (Fig. 1).4–6,19,20,23–30 Significant heterogeneity was observed between both types of reports and hospital registries reports. The scatter wide distribution in the funnel plot suggested the presence of reporting bias (Fig. 2A) but the small-study effect was excluded by the Harbord test (P=.48). Meta-regression analysis identified age (P<.001), fatality rates (P=0.04) and prevalence of CVD and 2 outlier results6,26 as the main sources of heterogeneity.

Summary of the studies included in the metanalysis.

| First author | Date | Journal | Age | males | N total | N dead | N CCVD | CVDdead | NHT | HT dead | NDM | DM dead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X.Yang4 | Feb 2020 | Lancet Resp | 58.25 | 35 | 52 | 32 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 7 | ||

| Q. Ruan5 | March 2020 | Intensive Care Med | 58.5 | 102 | 150 | 68 | 25 | 20 | 52 | 29 | 25 | 12 |

| F. Zhou6 | March 2020 | Lancet | 60.5 | 119 | 191 | 54 | 15 | 13 | 58 | 26 | 36 | 17 |

| MSCyB10 | May 29 2020 | website | 250273 | 20534 | 43420 | 10133 | 31800 | 24222 | 5532 | |||

| T. Chen18 | March 2020 | BMJ | 62 | 171 | 274 | 113 | 24 | 17 | 93 | 54 | 47 | 24 |

| RM. Inciardi20 | May 14 2020 | Eur Heart J | 67 | 99 | 26 | 53 | 19 | 63 | 17 | 30 | 12 | |

| Q. Deng23 | April 6 2020 | Int J Cardiol | 65 | 66 | 112 | 14 | 15 | 4 | 36 | 5 | 19 | 1 |

| C. Wu24 | March 2020 | JAMA Inter Med | 51 | 128 | 201 | 44 | 8 | 4 | 39 | 16 | 22 | 11 |

| ES. Rosenberg25 | May 11 2020 | JAMA | 65 | 858 | 1438 | 292 | 438 | 136 | 816 | 210 | 504 | 134 |

| R. Du26 | April 2020 | Eur Resp J | 57.6 | 97 | 179 | 21 | 29 | 17 | 58 | 13 | 33 | 6 |

| F. San Roman27 | Jun 17 2020 | Rev Esp Cardiol | 68 | 522 | 130 | 68 | 43 | 261 | 92 | |||

| C. Ferrando28 | July 9 2020 | Rev Esp Anest Reanim | 64 | 444 | 1004 | 203 | 91 | 38 | 329 | 115 | 151 | 61 |

| G. Grasselli29 | July 15 2020 | JAMA IM | 63 | 3188 | 3988 | 1926 | 533 | 342 | 1643 | 962 | 514 | 328 |

| S. Gupta30 | July 15 2020 | JAMA IM | 60.5 | 1436 | 2215 | 784 | 288 | 130 | 1322 | 540 | 861 | 352 |

| AM. Borobia31 | June 4 2020 | J Clin Med | 61 | 1074 | 2226 | 460 | 429 | 195 | 920 | 318 | 381 | 157 |

| NCP-ERT32 | March 2020 | China CDC Weekly | 22981 | 44672 | 1023 | 873 | 92 | 2683 | 161 | 1102 | 80 | |

| Total | 61.5 | 30699 | 307596 | 25724 | 46321 | 11213 | 40173 | 2466 | 28048 | 6734 |

CVD, cadiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; MSCyB, Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar; NC-ERT, Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Team.

We also analyzed the effect of CVD risk factors on mortality. Data from 28048 patients with diabetes was available. Diabetes was associated to higher mortality risk (OR, 2.41; 95%CI, 1.79–3.26; P<.001) (Fig. 3).4–6,19,20,23–26,28–31 Age (P<.01) and data source (P=.026) were the leading causes of heterogenicity (Fig. 2B). Sensitivity analyses suggested bias in the results of patients with diabetes; the funnel plot was not symmetrical and had a disperse distribution (Fig. 2B) and The Harbor test suggested a small-trial effect (P=.01). As shown in Fig. 4,5,6,19,20,23–26,28–31 hypertension was also associated to higher risk of death (OR, 2.60; 95%CI, 2.10–3.21; P<.001). In contrast, the funnel plot was more symmetrical and had less dispersion (Fig. 2C); moreover, the Harbor test excluded relevant biases or small-study effect (P=.39).

The metanalysis of currently available data suggests that patients with CVD and COVID-19 infection have more than 4-fold higher risk of mortality. Our results may have several clinical implications such as more strict measures for prevention of COVID-19 infection in patients with CVD as well as early and aggressive management of infected patients.38 The COVID-19 pandemic has irrupted in the medical community in terms of diagnosis, containment, and clinical management.15,16,39 The worldwide spread has increased the urgent need for relevant data; the meritorious reports from China were very illustrative and national reports have progressively increased the knowledge of this unpreceded outbreak.

Four key issues have been highlighted as priority in the field of the COVID-19 outbreak: clarifying the full spectrum of disease, how transmissible it is, identification of the infectors and, defining the risk factors for severe illness or death.15 CVD was outlined as a risk factor for poorer outcomes, from the first reports,5–7,19,40 and we conducted this meta-analysis aware of the increasing prevalence of the patients with CVD worldwide.41,42 Our results suggest that patients with CVD have more than a 4-fold higher risk of death once they get the COVID-19 infection. Clinical variables associated with poor in-hospital outcomes highlighted CVD as one of them.6,7 The National Health Commission of China designed and validated a risk score to predict severe COVID-19 disease, a combined end-point that included admission to the intensive care unit, invasive ventilation, or death.21 Our results might reflect that CVD should be taken as a relevant and independent risk factor in COVID-19 patients. We found differences in mortality rates between hospital registries and national reports but the risk associated with CVD was similar in both types of report which might reflect the reliability of national reports and endorse our results. Nonetheless, most clinical series had small sample sizes and were underpowered to assess the actual risk of death associated with CVD in COVID-19 patients. At least 2 hospital series have analyzed the impact of CVD on COVID-19 patients. A report from 99 patients admitted in Northern Italy hospitals, with only 53 patients with CVD, found higher mortality rates in an univariate analysis.20 A larger report with 522 patients from 2 Spanish hospitals described an independent association of CVD only with the combined end-point of death or respiratory insufficiency.27 The fact that both series were underpowered to achieve statistically significant results reinforces the need of our metanalysis.

The mechanisms that could explain the increased risk of death in CVD patients are not fully known.43,44 Patients with severe pneumonia, previous CVD, and older age are at higher risk of developing cardiac complications during and after pneumonia.18 Cardiac injury was detected in 19.7% of patients admitted with COVID-19 symptoms and it was associated with higher risk of in-hospital mortality (HR, 4.26; 95%CI, 1.92–9.49) in a single center study form Wuhan.45 A recent meta-analysis showed that myocardial injury could be detected in 21% of COVID-19 patients and it was 4 times higher in severe patients.46 More interestingly, myocardial injury has been reported as an equivalent to previous myocardial infarction in terms of mortality risk in COVID-19 patients.47 Prolonged fever and pro-inflammatory state are poorly tolerated in patients with CVD and, therefore, acute respiratory distress syndrome and respiratory failure, sepsis, acute cardiac injury, and heart failure, the most severe and common complications during exacerbation of COVID-19, are increased in patients with CVD.19,24,39,46,48,49 Low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc) have been clearly related to DM and cardiovascular disease50 and recent studies have linked low HDLc to higher risk of severe COVID-19.51

Patients with CVD have a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors52 and it can also, impair their prognosis. Our results also describe a significant effect of hypertension and diabetes on mortality. The antecedent of hypertension could not be analyzed in the Spanish national report because it was only registered from 18 March 2020.10 Hypertension and, more especially treatment in angiotensin-receptor blockers or angiotensin receptor antagonist, has received great interest because the COVID-19 virus is known to infect cells by the angiotensin receptor;53 nonetheless, there is no solid evidence to withdraw this treatment.45,54,55 Regardless of this treatment debate, our results found a clear increased risk of patients with hypertension or diabetes, that was even higher in national reports. Since significant heterogeneicity was observed in our results we conducted sensitivity analyses and excluded the small-studies effect;38 nonetheless, is difficult to be certain whether publication bias or studies’ sample size were the most determinant issue because of the presence of substantial heterogeneity. Diabetes is a well-established risk factor for CVD and atherosclerosis and recent metanalysis described an increased risk of mortality associated with DM (OR, 1.75; 95%CI, 1.31–2.36; P=.0002)56 and our study, with many more studies and patients, fully agrees with those findings.

National reports have been providing rapid and large-scale data from COVID-19 incidence and mortality and, in many cases, other relevant information. National reports have been previously used to analyse the effect of age on mortality in COVID-19 patients and demonstrated that age>50 is the threshold for increased mortality risk.57 In this new meta-analysis, we used the national COVID-19 report from Spain that included the percentage of patients with CVD and their mortality rates as well as many other comorbities. It should be noted that mortality risk associated with CVD in the Spanish and Chinese reports were identical and it should reflect the reliability of these data sources. Nonetheless, reports included only patients with confirmed infection that were tested before hospital admission and, therefore, they might reflect only most severe or clinically relevant cases. The criteria for testing, especially in the initial phases of the pandemic, were very different in each region and this was suggested as a key element for the differences in mortality rates.9 We believe that our results could reinforce the key role of infection prevention in patients with CVD but also, to implement rapid and aggressive diagnosis and treatment in these patients.16,45 Moreover, second surges of COVID-19 are being reported in several countries or regions and all the evidence from the first surge should be used to improve the management of the pandemic. Patients in the second surge are reported to be younger, with lower burden of overall and specific comorbidities but with longer PCR results.58 This clinical profile might tend to spread the infection and eventually infect patients with CVD. Our meta-analysis highlights that patients with established CVD are at very high-risk of mortality when they get the infection. Evidence supports early and aggressive treatment among patients with CVD because shorter periods of time from the onset of symptoms to the hospital admission have been related to lower mortality rates.7

4.1LimitationsOur study has several limitations, mainly derived from the limited evidence available. First of all, reports were based only on patients with laboratory-confirmed infection. Second, official and published data were used and we could not split the effect of different modalities of cardiovascular disease. Third, these findings are probably limited to the most severely ill patients (those that are finally diagnosed due to symptoms). Fourth, the prevalence of obesity was not reported in the publications and, therefore, the impact of excess of weight and its relationship with DM and other clinical features of the metabolic syndrome could not be analyzed. Finally, most national reports do not include the prevalence of CVD or the differential features of patients who died vs survivors. The National Report from Spain represented most patients in the study and in the sub-group of national reports and, therefore, results might not be representative world-wide. We believe that these limitations might have had a minimal effect on results representative and, moreover, might reinforce the need of fast-track publication of reports and clinical registries reporting such valuable data despite the hard conditions.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, the meta-analysis of 305370 patients highlights that patients with CVD and COVID-19 have more than 4-fold higher risk of mortality, as well as patients with hypertension or diabetes. More clinical and basic research is needed for elucidate the mechanism involved in the cardiovascular manifestations in COVID-19 infected patients and strategies to improve infections and outcomes in CVD patients. Our results should be taken into consideration for future surges of COVID-19 in order to implement preventive measures in patients with CVD.

- –

Patients with CVD are at increased risk of infections and have higher mortality rates for infectious diseases.

- –

Comorbidities, especially age or CVD, have been outlined as a risk factors for poorer outcomes in COVID-19 patients

- –

Patients with CVD and COVID-19 have a 4-fold higher risk of death.

- –

Diabetes or hypertension are associated with twice as high mortality risk in COVID-19.

Authors have no conflicts of interest related to the results of this study.

Investigators received the support from the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV CB16/11/00226 – CB16/11/00420).