The standardized use of laboratory blood tests will promote effective resource utilization, minimize waste, and improve healthcare services. The objective of this work is to develop a set of parameters that constitute essential preconfigured analytical profiles (PAPs) for the clinical management of patients with heart failure. A consensus-driven process was performed among a multidisciplinary team of 7 Spanish healthcare professionals working in hospitals located in different Spanish regions. A total of 6 PAPs were identified, aiming for different objectives: identifying the cause of heart failure (“de novo PAP”); monitoring the patient at various times and scenarios (“Outpatient follow-up PAP,” “Hospital admission PAP,” “Hospital evolution PAP,” “Titration and decompensation control PAP”); and titrating medication (“Drug titration PAP,” “Titration and decompensation control PAP”). The use and implementation of these PAPs by healthcare professionals should facilitate the standardization of patient care and potentially improve clinical outcomes and healthcare resource utilization.

El uso de análisis de laboratorio estandarizados podría mejorar la atención médica y la utilización de recursos sanitarios. El objetivo de este trabajo es desarrollar un listado de parámetros denominados perfiles analíticos preconfigurados (PAP) para el abordaje clínico de pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca. Se llevó a cabo un proceso de consenso por un equipo multidisciplinar de 7 profesionales sanitarios pertenecientes a hospitales de diferentes regiones españolas. Se identificó un total de 6 PAP, con diferentes objetivos: identificación de la causa de la insuficiencia cardiaca («de novo PAP»); monitorización («PAP de seguimiento ambulatorio», «PAP de admisión hospitalaria», «PAP de evolución hospitalaria», «PAP de titulación y control de descompensación»); y titulación («PAP de titulación de medicamentos», «PAP de titulación y control de descompensación»). El uso e implementación de estos PAP en el sistema sanitario debería facilitar la estandarización del cuidado del paciente, mejorar los resultados clínicos y la utilización de recursos.

In a context of increasing use of resources and healthcare expenditure, standardized use of laboratory blood tests will minimize waste, improve healthcare services, and promote the effective use of resources.1,2 The overuse of blood tests leads to high costs and a large carbon footprint, and increases the current problem of blood tubes’ shortages; also, the misuse of blood tests implies worse clinical management and possible harm to patients’ health.2–4 In particular, standardizing blood tests through the creation and use of profiles adjusted to the various stages and situations of care will have several advantages: improving the patient experience (fewer venipuncture events, less time/travel for outpatient blood taking); homogenizing clinical management; and allowing comparisons between different hospital databases, favoring research.5

Heart failure (HF) is a major concern in public health.6 In developed countries, roughly 2% of the adult population suffers from HF, a prevalence that increases exponentially with age: from less than 1% before the age of 50 to over 8% after the age of 75.7 HF is the largest cause of hospitalization for people over 65, accounts for more than 2% of Spain's healthcare expenditures, and is a common source of morbidity and mortality.6–9 The disease has a complex etiology and several risk factors.10 For example, iron deficiency is widespread in patients with chronic or acute HF, with both preserved or reduced ejection fraction11–14; consequently, it is advised to systematically measure iron parameters (serum ferritin and transferrin saturation) in patients with suspected HF, and during follow-up visits of patients with HF.6,15,16 Also, the 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines suggest the measurement of various biomarkers; however, these recommendations might not be completely followed in ordinary clinical practice.6 Therefore, standardization of laboratory blood test profiles for HF patients would be beneficial.

Despite the importance of standardization of laboratory blood tests, there is a paucity of studies, guidelines, and consensus in cardiology as in other medical fields. In a previous work, we introduced the concept of preconfigured analytical profiles (PAPs), a series of blood test profiles used for the clinical management of patients throughout their journey.17 PAPs, also called specific test panels, can be easily implemented in the hospital information technology systems to improve and standardize patient management at the click of a button.17 In our recently published work, we also studied the degree of implementation of PAPs in the management of HF in Spain and the opinion of healthcare professionals on their use.17 The study concluded that standardizing and homogenizing diagnostic and follow-up tests must be improved in patients with HF in Spanish hospitals, and that the experts consulted were in favor of their use.17 The objective of this work is to develop a set of parameters that constitute essential PAPs for the clinical management of patients with HF, through a driven-consensus process among a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals, including 3 cardiologists, 2 internists, and 2 laboratory analysts.

MethodsParticipantsThe study was led by a scientific committee (SC) that was comprised of a multidisciplinary team of seven members from centers across the Spanish territory: three cardiologists, 2 internists, and two laboratory heads.

Anima Strategic Consulting, a medical agency with a substantial experience in the healthcare field, was involved in the planning and acted as facilitator of the meetings and provider of the meeting summaries.

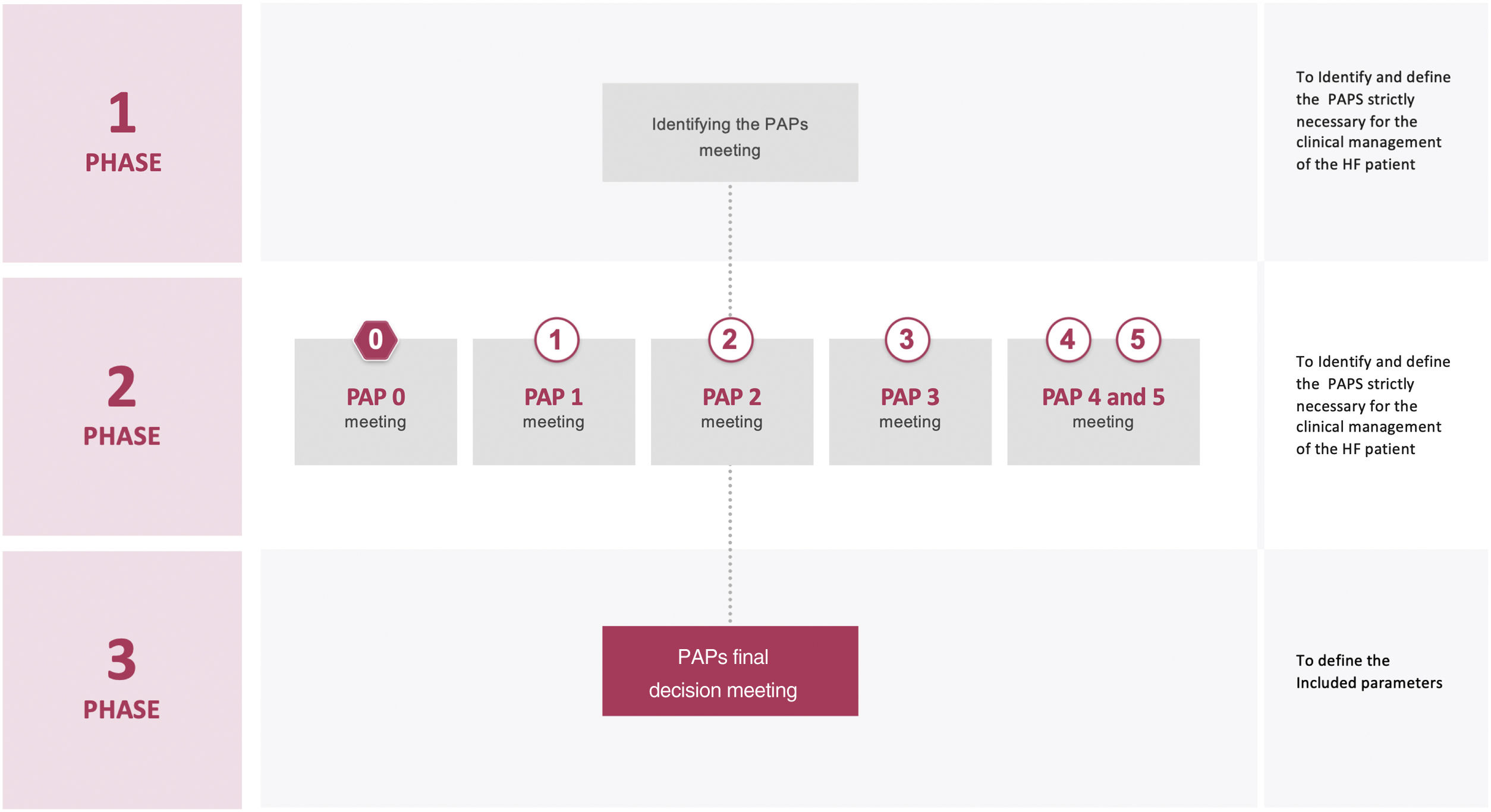

PhasesThe project was carried out in 4 phases (Fig. 1). In phase 1, a virtual meeting was conducted to decide the necessary PAPs to analyze during the HF patient journey. During phase 2, an online questionnaire and subsequent virtual meetings were held to discuss the parameters to be included in each PAP. Phase 3 consisted in a virtual meeting in which all PAPs and parameters were presented and discussed to have a broad perspective of the entire patient journey. In phase 4, the manuscript was drafted.

Phase 1 meetingThe nominal group technique was used to identify the essential PAPs for the clinical management of HF patients during their journey. It is a systematic, multistep group technique to elicit and rank group replies to a query or problem.18 This strategy has been used in many healthcare scenarios to create ideas or facilitate group consensus.19 The nominal group technique provides benefits over traditional focus groups and other qualitative research methodologies by providing an egalitarian method of participation and encouraging all group members to contribute with ideas.20 Indeed, because of the method's structure, one group member cannot dominate the conversation, and the group leader has less influence (and hence less possible bias) than in conventional focus groups.18–20

The meeting was developed in several steps: an individual generation of PAPs in HF; a round-robin recording of them; a discussion; a ranking; a tally of the ranking; and, finally, a review of the ranking of the PAPs and the selection of the essential ones.

Phase 2 meetingsA modified version of the nominal group technique was used to obtain a PAP proposal at each of the meetings. Parameters to be included in each PAP were individually identified before the meeting (online questionnaire) and sent to the facilitators to be recorded. Meetings consisted of a presentation of the results of the online questionnaire by the facilitators, and a discussion and a debate by the SC. The need to include additional parameters was also discussed. Each meeting ended with a consensus proposal of the parameters to be included in the PAP discussed.

Phase 3 meetingThe proposals of all the PAPs generated during phase 2, were presented and discussed to have a broad vision of their use in the HF patient journey. Finally, the parameters of all the PAPs were defined and agreed upon.

Online questionnaireIn phase 2, before each meeting, SC members sent to Anima Strategic Consulting their proposed parameters for each PAP, using an online questionnaire.

Concept and methodology of the meetingsThe SC considered to develop each PAP using the minimum number of parameters. This rule was taken into account during all phases of the project.

Each meeting was structured to promote equal participation of all the members of the SC. Participants were informed that the purpose of the meeting was to tap into their unique insights, knowledge, and experiences; they were also informed of the ground rules for the meeting and asked to work independently to develop their own ideas. To help ensure that a wide array of responses would be generated, participants were encouraged to think broadly. Notes were taken by the facilitators from all meetings and a written summary was made and shared with all participants. All meetings were recorded after consent was given.

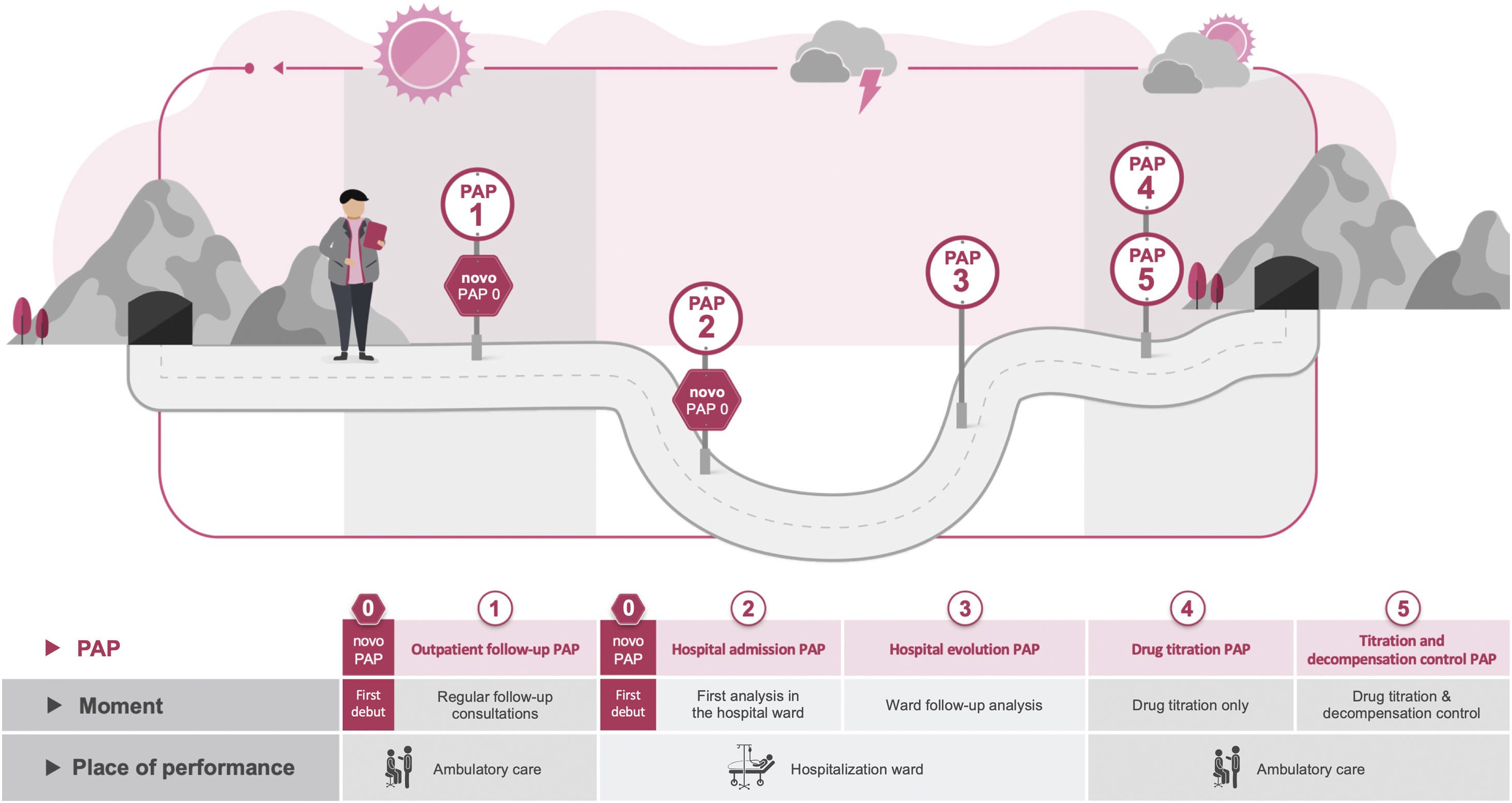

ResultsEssential PAPs for HF clinical managementWe identified 6 PAPs for the clinical management of HF. Fig. 2 depicts the timing and location of each PAP in the HF patient journey.

The “de novo PAP” (PAP 0) must be performed to determine the cause of HF. It may be used as a supplement to PAP 1 or PAP 2, depending on where the patient is diagnosed (ambulatory care or hospital ward, respectively).

The “Outpatient follow-up PAP” (PAP 1) serves to monitor HF patients every 3/6/12 months (depending on the doctor's practice), when the patient's medical status is stable and desirably before the ambulatory care visit.

The “Hospital admission PAP” (PAP 2) should be examined when the patient is admitted to the hospital ward following a decompensation.

The “Hospital evolution PAP” (PAP 3) should be assessed every 2 to 3 days, or whenever there is a major change in treatment.

The “Drug titration PAP” (PAP 4) should be analyzed at the outpatient care, exclusively for drug titration, and every two to three weeks on average (until titration).

Finally, the “Titration and decompensation control PAP” (PAP 5) should be determined in outpatient treatment after the discharge from the hospital of unstable patients. This PAP has a dual purpose: to titrate the medications and to observe the patient's progression after discharge till stability.

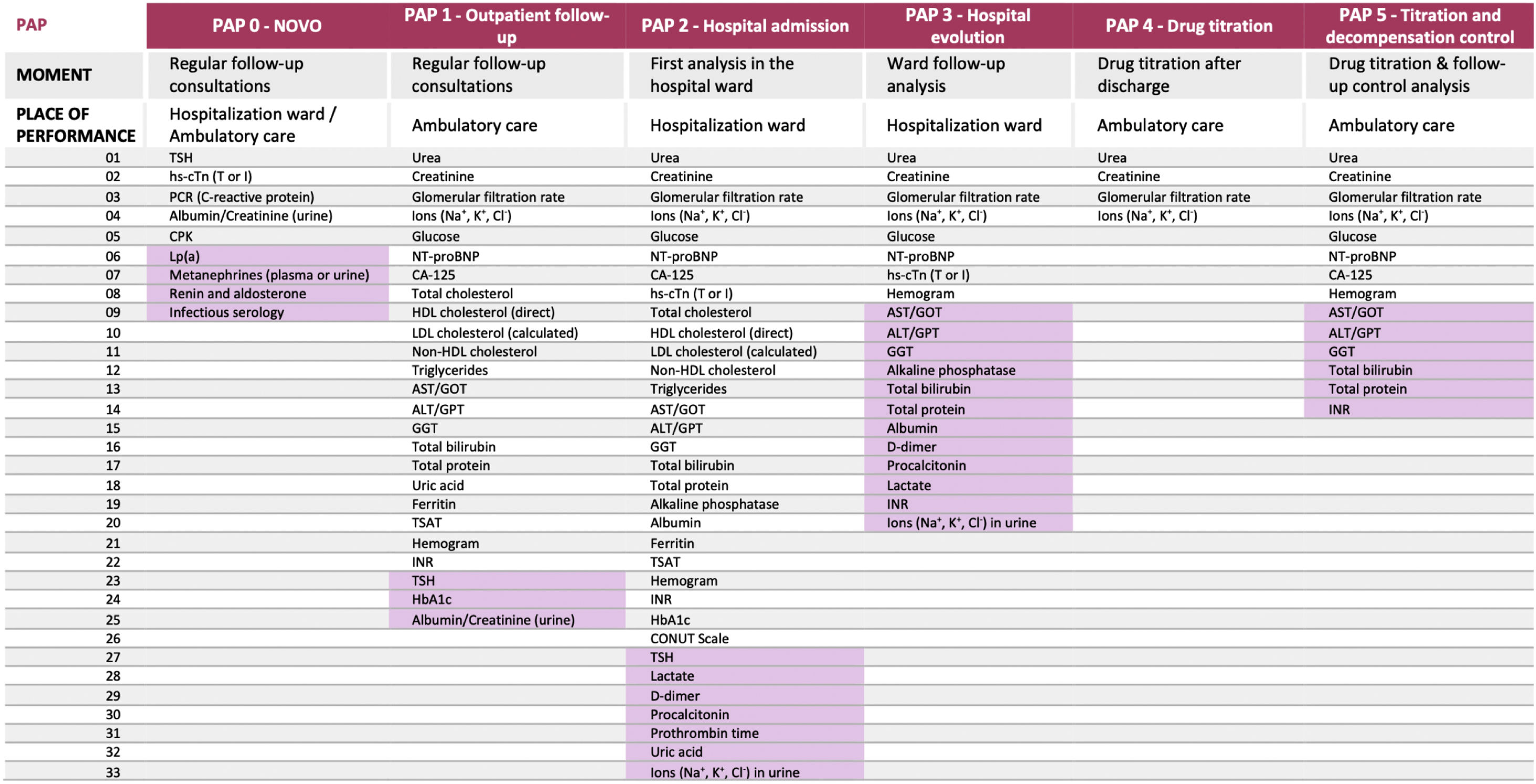

Regarding the composition of the PAPs, we agreed on standard parameters and conditional ones that should only be measured under certain circumstances and on the basis of the clinical conditions.

Consensus on the parameters of the essential PAPs for HF clinical managementDe novo PAP (PAP 0)Table 1 of the supplementary data shows the “de novo PAP” creation process, through the different phases and the final result. The 4 parameters provided in the online questionnaire were established as standard. It is worth mentioning that of the thyroid hormones initially proposed, only the thyroid stimulating hormone was considered relevant for measurement. In the phase 2 meeting, another series of parameters were proposed and resulted in consensus, although they will be measured conditionally, with the exception of creatine phosphokinase, which is considered a standard parameter.

Outpatient follow-up PAP (PAP 1)As for the parameters to be included in the “Outpatient follow-up PAP”, the SC decided by consensus to include the ones provided in the online questionnaire that reached 71.4% of the votes, except for the alkaline phosphatase (Table 2 of the supplementary data). Only the thyroid stimulating hormone was considered as a conditional parameter. Aspartate transaminase and gamma-glutamyl transferase were considered conditional parameters in phase 2 of the project, finally becoming standard in phase 3.

Of the parameters proposed in the phase 2 meeting, 1 was finally included as standard (non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and 2 as conditional (hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] and albumin/creatinine ratio in spot urine).

Hospital admission PAP (PAP 2)Table 3 of the supplementary data displays the outcomes of the “Hospital admission PAP” development. All the parameters indicated by the SC in the online questionnaire were selected for final inclusion in this PAP. Only the prothrombin time and the uric acid were finally defined as conditional parameters, the rest as standard. Also, consensus was reached to include all parameters proposed during the phase 2 meeting, except for albumin/creatinine ratio in spot urine. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn; T or I), non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and controlling nutritional status (CONUT) scale were established as standard parameters, and the rest as conditional.

Hospital evolution PAP (PAP 3)All parameters proposed by the SC in the online questionnaire were approved for inclusion in the “Hospital evolution PAP”, except for uric acid (Table 4 of the supplementary data). The parameters that reached 85.7% of the votes were established as standard and the rest as conditional. Regarding the variables provided by the SC during the phase 2 meeting, a total of 6 parameters were included in this PAP; the evaluation of hs-cTn (T or I) was considered as standard and the rest as conditional.

Drug titration PAP (PAP 4) and titration and decompensation control PAP (PAP 5)The last PAP proposed during the online questionnaire was the “Titration and decompensation control PAP”. However, during the phase 2 meeting, a new PAP was generated, which can be used independently when drug titration is necessary for patients with HF: the “Drug titration PAP”.

The process of finding consensus on the parameters for both PAPs can be seen in Table 5 of the supplementary data. The procedure resulted in 10 standard and 6 conditional parameters for the “Titration and decompensation control PAP” and 6 standard parameters for the “Drug titration PAP”.

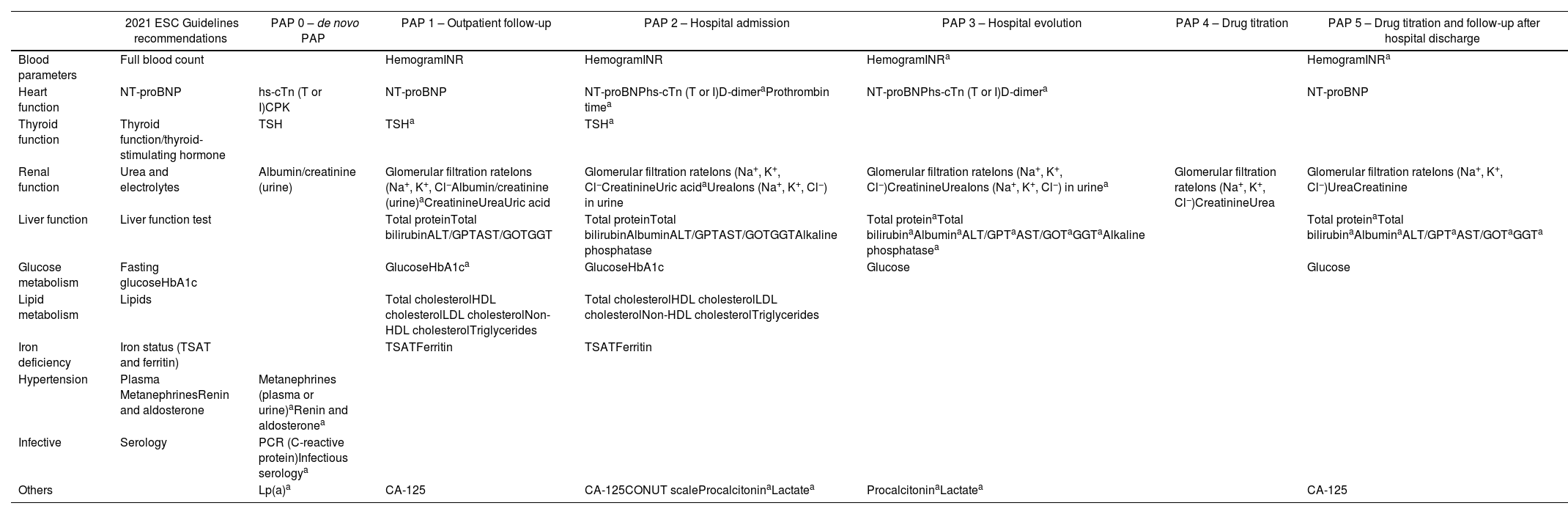

DiscussionIn this study, we identified 6 essential PAPs for the clinical management of HF patients (Fig. 3). These PAPs have different objectives: identifying the cause of the HF (“de novo PAP”); following up on the patient at different times and places (“Outpatient follow-up PAP”, “Hospital admission PAP”, “Hospital evolution PAP”, “Titration and decompensation control PAP”); and titrating the medication (“Drug titration”, “Titration and decompensation control PAP”). These PAPs involve different laboratory tests that, through the use of different parameters, measure organ damage or function (heart, thyroid, kidneys, and liver), metabolism (glucose and lipid), and iron deficiency, among others. Table 1 shows all the PAPs developed in this study for the clinical management of HF patients. We show that the PAPs developed in this study are consistent with the recommendations of the ESC 2021 guidelines, but are more explicit and detailed in terms of the parameters to be monitored and the location and time of the measurements. In addition, to avoid wasting health resources, it should be checked before requesting any analyses if the required data are already available from another recent analysis or if the same request was recently made.

Parameters inside the preconfigured analytical profiles (PAPs). The cells shaded represent those parameters that should be requested conditionally, depending on previous tests or results. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; CA-125, cancer antigen 125; CONUT, controlling nutritional status; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; GPT, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; HbA1C, hemoglobin A1C; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hs-cTn, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin; INR, international normalized ratio; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; P2M, proposed in phase 2 meetings; POQ, proposed in the online questionnaire; TSAT, transferrin saturation; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Comparison of 2021 European Society of Cardiology guidelines and preconfigured analytical profiles (PAPs).

| 2021 ESC Guidelines recommendations | PAP 0 – de novo PAP | PAP 1 – Outpatient follow-up | PAP 2 – Hospital admission | PAP 3 – Hospital evolution | PAP 4 – Drug titration | PAP 5 – Drug titration and follow-up after hospital discharge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood parameters | Full blood count | HemogramINR | HemogramINR | HemogramINRa | HemogramINRa | ||

| Heart function | NT-proBNP | hs-cTn (T or I)CPK | NT-proBNP | NT-proBNPhs-cTn (T or I)D-dimeraProthrombin timea | NT-proBNPhs-cTn (T or I)D-dimera | NT-proBNP | |

| Thyroid function | Thyroid function/thyroid-stimulating hormone | TSH | TSHa | TSHa | |||

| Renal function | Urea and electrolytes | Albumin/creatinine (urine) | Glomerular filtration rateIons (Na+, K+, Cl−Albumin/creatinine (urine)aCreatinineUreaUric acid | Glomerular filtration rateIons (Na+, K+, Cl−CreatinineUric acidaUreaIons (Na+, K+, Cl−) in urine | Glomerular filtration rateIons (Na+, K+, Cl−)CreatinineUreaIons (Na+, K+, Cl−) in urinea | Glomerular filtration rateIons (Na+, K+, Cl−)CreatinineUrea | Glomerular filtration rateIons (Na+, K+, Cl−)UreaCreatinine |

| Liver function | Liver function test | Total proteinTotal bilirubinALT/GPTAST/GOTGGT | Total proteinTotal bilirubinAlbuminALT/GPTAST/GOTGGTAlkaline phosphatase | Total proteinaTotal bilirubinaAlbuminaALT/GPTaAST/GOTaGGTaAlkaline phosphatasea | Total proteinaTotal bilirubinaAlbuminaALT/GPTaAST/GOTaGGTa | ||

| Glucose metabolism | Fasting glucoseHbA1c | GlucoseHbA1ca | GlucoseHbA1c | Glucose | Glucose | ||

| Lipid metabolism | Lipids | Total cholesterolHDL cholesterolLDL cholesterolNon-HDL cholesterolTriglycerides | Total cholesterolHDL cholesterolLDL cholesterolNon-HDL cholesterolTriglycerides | ||||

| Iron deficiency | Iron status (TSAT and ferritin) | TSATFerritin | TSATFerritin | ||||

| Hypertension | Plasma MetanephrinesRenin and aldosterone | Metanephrines (plasma or urine)aRenin and aldosteronea | |||||

| Infective | Serology | PCR (C-reactive protein)Infectious serologya | |||||

| Others | Lp(a)a | CA-125 | CA-125CONUT scaleProcalcitoninaLactatea | ProcalcitoninaLactatea | CA-125 |

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; CA-125, cancer antigen 125; CONUT, controlling nutritional status; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; GPT, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; HbA1C, hemoglobin A1C; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hs-cTn, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin; INR, international normalized ratio; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; P2M, proposed in phase 2 meetings; POQ, proposed in the online questionnaire; TSAT, transferrin saturation; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

We developed “de novo PAP” (PAP 0) to obtain data on the causes of HF. The importance of establishing the etiology of HF is essential to choose the correct treatment and follow-up for each patient. In particular, the data from the “de novo PAP” will help the physician to establish a tailored therapeutic strategy that could even achieve the cessation of HF through the cure of the cause. The “de novo PAP” includes parameters that identify causes like myocardial infarction (hs-cTn), hypothyroidism (thyroid stimulating hormone), kidney failure (albumin/creatinine ratio in spot urine), inflammation (C-reactive protein), and diabetes (HbA1c). Additional parameters, indicated as conditional, can identify less common causes of HF, including pheochromocytoma (plasma metanephrines), adrenal gland disorder (renin, aldosterone), virus infections (infectious serology), and disorder of lipid metabolism (lipoprotein(a)). The data provided by this PAP could even be used to reveal undiagnosed diseases in the patient. Also, knowing the HF causes could lead to a multidisciplinary management of the patient, resulting in a decrease in mortality and readmission rates, with a possible improvement in the use of healthcare resources. Finally, according to a Cochrane systematic review, a multidisciplinary management is better than other disease management interventions for HF patients.21

The “Outpatient follow-up PAP” (PAP 1), “Hospital admission PAP” (PAP 2), and “Hospital evolution PAP” (PAP 3) have several parameters in common. Most of them are included in the recommendations of the ESC guidelines for 2021: hemogram, urea, electrolytes, parameters of the thyroid function, fasting glucose, HbA1C, lipids, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, liver function test, and iron status (transferrin saturation and ferritin).6 Iron deficiency is frequently associated with HF and is linked to poor physical performance, low health-related quality of life, and high risk of death, independently of whether it is accompanied by anemia.15,16,22,23 The evaluation of iron deficiency is therefore necessary for the clinical management of patients with HF, as recommended by the ESC 2021 guidelines,6 and patients with iron deficiency may be treated with supplements.24–27 A study of Delgado et al. demonstrates that iron therapy in HF patients results not only in a good clinical effect, but also in an economic gain from the perspective of health management.28 Moreover, several investigations, including a meta-analysis conducted by Khan in 2020 and 2 clinical trials (CONFIRM-HF and AFFIRM-AHF), have shown that therapy with ferric carboxymaltose in HF patients lowers the risk of hospitalization. In turn, this is likely linked to a reduction in expenditures.25–27,29 Finally, PAPs may be used to standardize the assessment of iron deficiency during treatment of patients with HF, helping to eradicate its deleterious effects on patient health and reducing costs for the healthcare system.

Concerning the drug titration PAPs (PAP 4 and 5), this consensus is consistent with the current international HF guidelines. Such guidelines recommend starting with a low dose of drug (starting dose), followed by up-titration to target (or the maximum tolerable dose). This process must be carried out under close medical surveillance to monitor for kidney function, potassium levels, hypotensive episodes, bradycardia, and other potential side effects.6,30 In line with this, a consensus was reached in this study on the inclusion of parameters indicative of renal function (urea; creatinine; estimated glomerular filtration rate; and Na+, K+, and Cl− ions) in the “Drug titration PAP”. The inclusion of Na+, K+, and Cl− evaluation was also due to the frequent use of loop diuretics in the treatment of HF patients, and the recommendation of their titration by clinical guidelines.6 In fact, it is advised to lower the dosage of loop diuretics in patients who are stable and show no obvious indicators of volume overload and, to obtain this parameter, the levels of the three ions (Na+, K+, and Cl−) must be evaluated.

Finally, the “Drug titration PAP” (PAP 4) can be used whenever required and can also be combined with other PAPs, as for example when monitoring the patient; and the “Titration and decompensation control PAP” (PAP 5) provides the necessary information to the clinician for the proper treatment of HF patients at Hospital discharge.

This research has some limitations, including the relatively small sample size; however, our sample is representative, as it consists of experts from different types of hospitals and various areas, with a diverse range of medical personnel. Another limitation is that the SC consisted only of experts from Spain, and their experience with the patient is centered on the Spanish public healthcare system. Therefore, clinicians with expertise in different healthcare systems should evaluate the applicability of our PAPs to their clinical HF practice, adapting or discarding the ones that they deem inappropriate. Finally, every session was held online. This form of meeting may result in prejudiced communication, although this technology may also provide advantages, such as improved engagement.31

During the past few decades, several studies have tried to improve the use of laboratory testing in hospitals and in primary care.32–35 Modifications to computerized ordering systems, targeted education, and feedback on ordering behavior are examples of strategies to promote the use of diagnostic tests.36–41 This work intends to contribute to these efforts by developing PAPs for the clinical management of HF patients, as recommended by the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Sociedad Española de Cardiología; SEC), the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine (Sociedad Española de Medicina de Urgencias y Emergencias; SEMES), and the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna; SEMI).42 Our work builds on previous research on the use of PAPs in HF and expert opinion in the Spanish setting. It is the first study to recommend PAPs for the diagnosis and follow-up of HF patients through their whole journey, using a driven-consensus process. This could serve as a starting point for the validation and use of PAPs in HF, helping to standardize HF diagnosis and follow-up throughout the national healthcare system, stimulating research, saving costs, and leading to better clinical outcomes. Additionally, this work could serve as a model to develop PAPs in other pathologies and medical fields, and therefore improve the healthcare system and patients’ outcome.

ConclusionsHealthcare management is currently undergoing digitalization, automation, and homogenization of processes. The burden and cost of healthcare is increasing in developed countries, and predictions show that this trend will continue in the near future. The correct use of automated and homogenized analytical tests may be a solution to reduce costs and ensure a better clinical management of patients. In this project, we identified six essential PAPs for the correct clinical management of patients with HF, which should be used at different times and places during the patient journey. The use and implementation of these PAPs by healthcare professionals would imply an improvement and standardization of HF patient care and possibly a consequent improvement in patient outcomes and utilization of healthcare resources.

FundingVifor Pharma S.L. Spain provided financial support to this work but had no role in the data collection and analysis, or in the development of this publication.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed to study design, conception, data interpretation, drafting the manuscript and revised and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone.

The authors would like to thank Anima Strategic Consulting for fieldwork and medical writing services and methodological support and Vifor Pharma for providing this service.

Abbreviations: HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HF: heart failure; hs-cTn: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin; PAP: preconfigured analytical profile; SC: scientific committee.