To describe the cardiovascular risk factors, lifestyle and cardiovascular treatment adherence of cardiologists in Latin America, Portugal, and Spain.

MethodsSeventeen Scientific Societies of Cardiology from Latin America, Portugal, and Spain were invited to participate. Each member was sent by email a link to an electronic questionnaire to be answered anonymously. The survey was divided into 4 sections: general characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, nutritional survey based on Mediterranean diet recommendations and breakfast habits, and physical activity.

ResultsA total of 1470 physicians (median age 49 years; IQR, 38.0–60.0 years; 61.4% women; 95% cardiologists) completed the questionnaire. The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was low: hypertension (23.5%), hyperlipidemia (25.1%), diabetes (6.7%), and active smokers (5.5%). Median body mass index was 24.7kg/m2 (IQR, 22.5–27.1kg/m2). Previous heart disease was low (7.3%). The PREDIMED score showed a low adherence to the Mediterranean diet 7.0 (IQR, 5.0–9.0). Physical activity analysis showed moderate activity.

ConclusionsDespite the heterogeneity of the sample and the limited rate of responses, this study provides the first data regarding cardiovascular risk factors, lifestyle, and cardiovascular treatment adherence of cardiologists in Latin America, Portugal, and Spain. Cardiologists are relatively aware of the importance of controlling cardiovascular risk factors although there is much room for improvement.

Describir los factores de riesgo cardiovasculares, el estilo de vida y la adherencia al tratamiento cardiovascular de los cardiólogos en América Latina, Portugal y España.

MétodosParticiparon 17 Sociedades Científicas de Cardiología en América Latina, Portugal y España. Cada miembro recibió por correo electrónico un enlace a un cuestionario electrónico, que se respondió de forma anónima. La encuesta se dividió en 4 secciones: características generales, factores de riesgo cardiovascular, encuesta nutricional basada en las recomendaciones de la dieta mediterránea y hábitos de desayuno, y actividad física.

ResultadosUn total de 1.470 médicos (mediana de edad de 49 años; rango RIC: 38,0-60,0 años; 61,4% mujeres; 95% cardiólogos) cumplimentaron el cuestionario. La prevalencia de factores de riesgo cardiovascular fue baja: hipertensión (23,5%), hiperlipidemia (25,1%), diabetes (6,7%) y fumadores activos (5,5%). El índice de masa corporal mediano fue de 24,7kg/m2 (RIC: 22,5-27,1kg/m2). La cardiopatía previa fue baja (7,3%). La puntuación PREDIMED mostró una baja adherencia a la dieta mediterránea 7,0 (RIC: 5,0-9,0). El análisis de actividad física mostró actividad moderada.

ConclusionesA pesar de la heterogeneidad de la muestra y la baja tasa de respuesta, este trabajo proporciona los primeros datos sobre los factores de riesgo cardiovasculares, el estilo de vida y la adherencia al tratamiento cardiovascular de los cardiólogos en América Latina, Portugal y España. Los cardiólogos son relativamente conscientes de la importancia de controlar los factores de riesgo cardiovascular, aunque aún hay mucho margen de mejora.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide.1 The cornerstone for the prevention of cardiovascular disease is the promotion of a healthy lifestyle together with the identification and treatment of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF). Attaining those healthy habits should be a therapeutic goal for the entire population. Unfortunately, it is well known that compliance with lifestyle recommendations is poor among the general population.

Cardiologists should promote healthy lifestyles, adequate CVRF control and good medication adherence in each visit, for primary and secondary prevention, in order to reduce morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular disease. Despite these recommendations are well known by physicians, it is uncertain whether they follow them in their lives.

The aim of this study was to analyze CVRF, lifestyle, and adherence to cardiovascular treatment of cardiologists in Latin America, Portugal, and Spain.

MethodsPopulationSeventeen Scientific Societies of Cardiology in Latin America, Portugal, and Spain were invited to participate. Of these, finally 14 agreed to take part in the survey: Argentinian Federation of Cardiology, Bolivian Society of Cardiology, Chilean Society of Cardiology, Colombian Society of Cardiology, Costa Rican Cardiology Association, Dominican Society of Cardiology, Ecuadorian Society of Cardiology, Guatemalan Cardiology Association, Mexican National Association of Cardiologists, Paraguayan Society of Cardiology, Peruvian Society of Cardiology, Portuguese Society of Cardiology, Spanish Society of Cardiology, and Uruguayan Society of Cardiology.

Each Scientific Society sent to their members, via email, a link to an electronic questionnaire survey, which was answered anonymously. The estimated response time of the survey was 5min. The link was available for 3 months. Each Scientific Society sent twice to their members a reminder of the survey during that period of time. The questionnaire was in Spanish, except for Brazil and Portugal that was in Portuguese. There was no economic incentive for those physicians who answered the questionnaire.

The survey was divided into 4 sections: (1) sociodemographic data (sex, gender, civil status, specialty, and subspecialty); (2) CVRF (hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus [DM], smoking habits, obesity/central obesity, prior ischemic heart disease) as well as whether physicians followed the recommendations performed by the guidelines about the management of cardiovascular disease and their adherence to treatment; (3) nutritional survey based on the Mediterranean diet recommendations analyzed by the MEDAS PREDIMED questionnaire.2,3 Breakfast habits were analyzed based on the analysis of the PESA study. Skipping breakfast was defined as consuming <5% of total daily energy4; and (4) physical activity (PA) habits based on the international PA questionnaire employing the short version (included 4 generic items) to facilitate the answer, this questionnaire enables a self-administered method to obtain internationally comparable data on health-related PA, and classify patients between low, moderate or high grade of PA. The results of this section were expressed as METS-minute/week.5

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Normal distribution was tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Quantitative data were expressed as median and interquartile range [IQR] and qualitative data as absolute number and percentage. Associations between qualitative variables were analyzed by the chi-square test. Associations between quantitative variables were analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test. Differences were considered statistically significant with a P value <.05.

ResultsOut of the 12799 potential target physicians, 1470 (11.4%) responses were obtained and analyzed. Eight hundred and seventy-five (61.4%) of them were female (45 responders did not define their gender). Median age was 49 [IQR, 38.0–60.0] years and 1138 (79.8%) lived in couple (44 responders did not define their civil status). All respondents were cardiologist selected by each national society 1378 (95%), although 5% of them did not complete the proper box in the form. Out of them, 715 (55.1%) were clinical cardiologists.

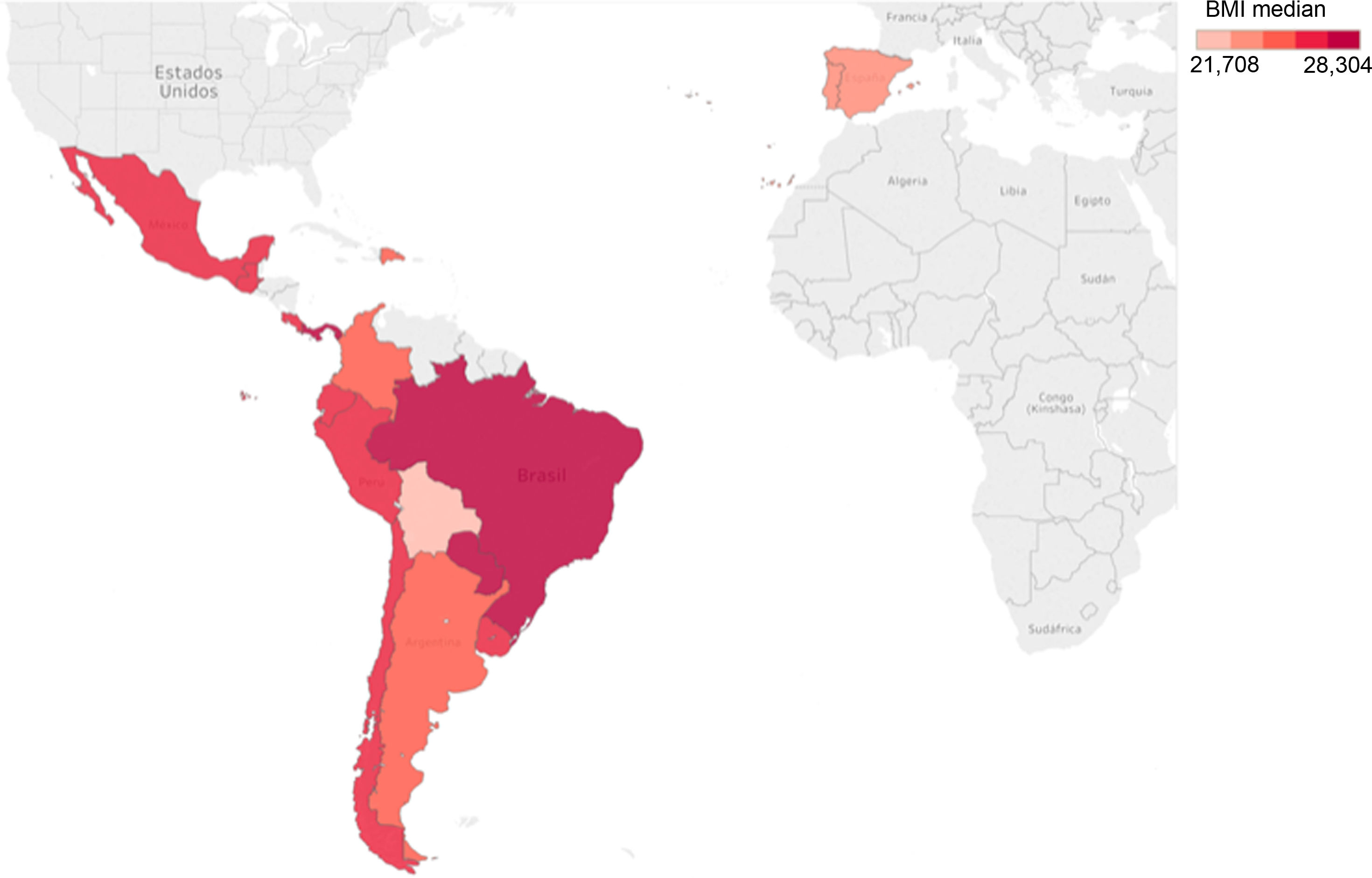

Cardiovascular risk factors, heart disease, and treatment adherenceThe prevalence of CVRF was low: hypertension (23.5%), hyperlipidemia (25.1%), DM (6.7%), and active smokers (5.5%) (Fig. 1). Median body mass index (BMI) was 24.7kg/m2 [IQR, 22.5–27.1] and abdominal waist circumference was 89.0cm [IQR, 77.0–97.0] (Fig. 2). Previous heart disease was low (7.3%). With regard to medication adherence, 56.8% of responders reported <50% adherence to treatment.

NutritionRegarding nutritional parameters, 21.3% of responders ate ≥4 cereal portions per day. Most of the responders (56.7%) ingested between 5% and 20% of the percentage of daily energy at breakfast. The analysis of the PREDIMED score showed a low adherence to the Mediterranean diet (7.0 [IQR, 5.0–9.0]).

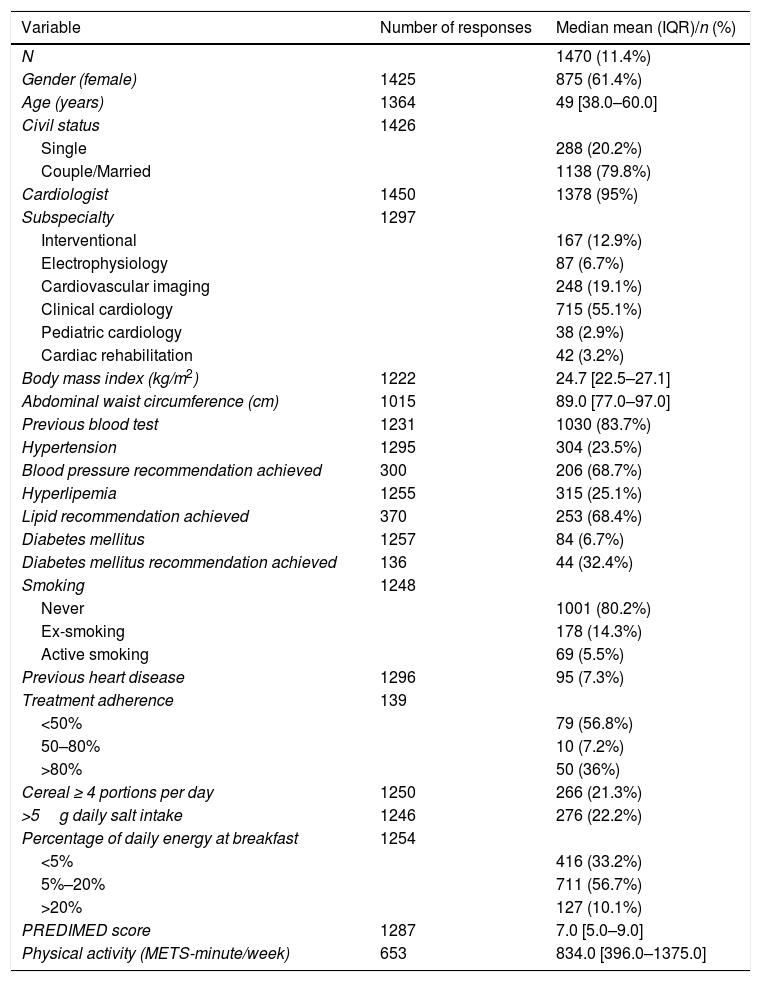

Physical activityOverall, physicians based on the international PA questionnaire reported a moderate PA, with a median value of 834.0 [IQR, 396.0–1375.0] METS-minute/week (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of the population.

| Variable | Number of responses | Median mean (IQR)/n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| N | 1470 (11.4%) | |

| Gender (female) | 1425 | 875 (61.4%) |

| Age (years) | 1364 | 49 [38.0–60.0] |

| Civil status | 1426 | |

| Single | 288 (20.2%) | |

| Couple/Married | 1138 (79.8%) | |

| Cardiologist | 1450 | 1378 (95%) |

| Subspecialty | 1297 | |

| Interventional | 167 (12.9%) | |

| Electrophysiology | 87 (6.7%) | |

| Cardiovascular imaging | 248 (19.1%) | |

| Clinical cardiology | 715 (55.1%) | |

| Pediatric cardiology | 38 (2.9%) | |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 42 (3.2%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1222 | 24.7 [22.5–27.1] |

| Abdominal waist circumference (cm) | 1015 | 89.0 [77.0–97.0] |

| Previous blood test | 1231 | 1030 (83.7%) |

| Hypertension | 1295 | 304 (23.5%) |

| Blood pressure recommendation achieved | 300 | 206 (68.7%) |

| Hyperlipemia | 1255 | 315 (25.1%) |

| Lipid recommendation achieved | 370 | 253 (68.4%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1257 | 84 (6.7%) |

| Diabetes mellitus recommendation achieved | 136 | 44 (32.4%) |

| Smoking | 1248 | |

| Never | 1001 (80.2%) | |

| Ex-smoking | 178 (14.3%) | |

| Active smoking | 69 (5.5%) | |

| Previous heart disease | 1296 | 95 (7.3%) |

| Treatment adherence | 139 | |

| <50% | 79 (56.8%) | |

| 50–80% | 10 (7.2%) | |

| >80% | 50 (36%) | |

| Cereal ≥ 4 portions per day | 1250 | 266 (21.3%) |

| >5g daily salt intake | 1246 | 276 (22.2%) |

| Percentage of daily energy at breakfast | 1254 | |

| <5% | 416 (33.2%) | |

| 5%–20% | 711 (56.7%) | |

| >20% | 127 (10.1%) | |

| PREDIMED score | 1287 | 7.0 [5.0–9.0] |

| Physical activity (METS-minute/week) | 653 | 834.0 [396.0–1375.0] |

Data are expressed as no. (%) or median [interquartile range].

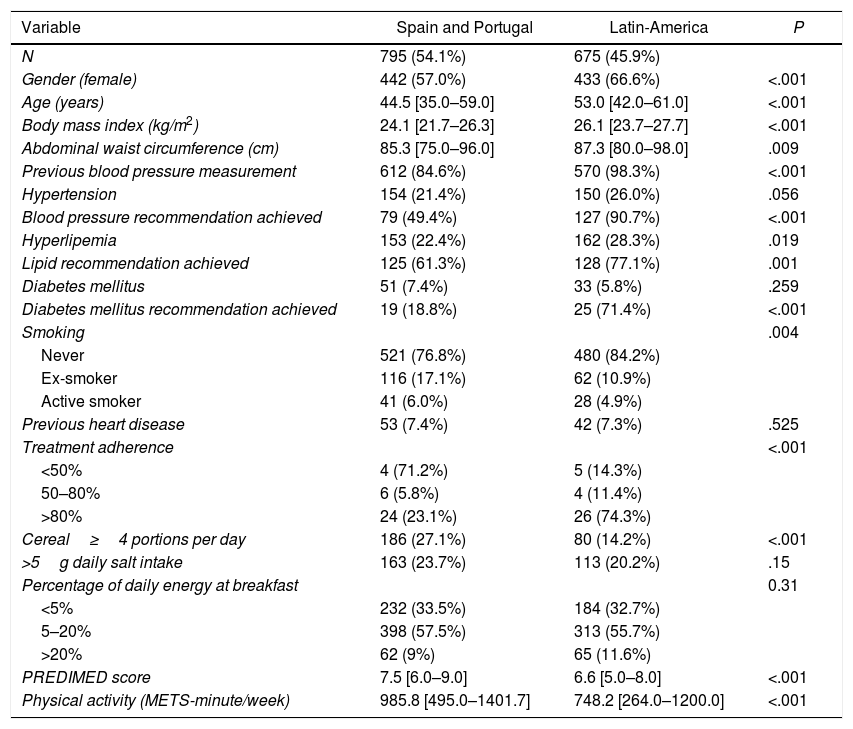

Among the responders, 795 (54.1%) were from Portugal and Spain and 675 (45.9%) from Latin-America. More women answered the survey in Latin-America versus Europe (433 [66.6%] and 442 [57.0%] respectively; P<.001). Physicians from Portugal and Spain were younger than those from Latin-America. BMI and abdominal waist circumference were higher in Latin-America, but blood pressure values, in Portugal and Spain. No significant differences were found regarding hypertension, hyperlipidemia or DM between both groups. By contrast, the prevalence of active smokers and ex-smokers were significantly higher in Portugal and Spain when compared with Latin-America. Regarding treatment adherence, Latin-America reported a higher adherence (Table 2).

Comparison between Spain–Portugal and Latin-America.

| Variable | Spain and Portugal | Latin-America | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 795 (54.1%) | 675 (45.9%) | |

| Gender (female) | 442 (57.0%) | 433 (66.6%) | <.001 |

| Age (years) | 44.5 [35.0–59.0] | 53.0 [42.0–61.0] | <.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.1 [21.7–26.3] | 26.1 [23.7–27.7] | <.001 |

| Abdominal waist circumference (cm) | 85.3 [75.0–96.0] | 87.3 [80.0–98.0] | .009 |

| Previous blood pressure measurement | 612 (84.6%) | 570 (98.3%) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 154 (21.4%) | 150 (26.0%) | .056 |

| Blood pressure recommendation achieved | 79 (49.4%) | 127 (90.7%) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipemia | 153 (22.4%) | 162 (28.3%) | .019 |

| Lipid recommendation achieved | 125 (61.3%) | 128 (77.1%) | .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 51 (7.4%) | 33 (5.8%) | .259 |

| Diabetes mellitus recommendation achieved | 19 (18.8%) | 25 (71.4%) | <.001 |

| Smoking | .004 | ||

| Never | 521 (76.8%) | 480 (84.2%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 116 (17.1%) | 62 (10.9%) | |

| Active smoker | 41 (6.0%) | 28 (4.9%) | |

| Previous heart disease | 53 (7.4%) | 42 (7.3%) | .525 |

| Treatment adherence | <.001 | ||

| <50% | 4 (71.2%) | 5 (14.3%) | |

| 50–80% | 6 (5.8%) | 4 (11.4%) | |

| >80% | 24 (23.1%) | 26 (74.3%) | |

| Cereal≥4 portions per day | 186 (27.1%) | 80 (14.2%) | <.001 |

| >5g daily salt intake | 163 (23.7%) | 113 (20.2%) | .15 |

| Percentage of daily energy at breakfast | 0.31 | ||

| <5% | 232 (33.5%) | 184 (32.7%) | |

| 5–20% | 398 (57.5%) | 313 (55.7%) | |

| >20% | 62 (9%) | 65 (11.6%) | |

| PREDIMED score | 7.5 [6.0–9.0] | 6.6 [5.0–8.0] | <.001 |

| Physical activity (METS-minute/week) | 985.8 [495.0–1401.7] | 748.2 [264.0–1200.0] | <.001 |

Data are expressed as no. (%) or median [interquartile range].

Regarding nutritional parameters, despite adherence to the Mediterranean diet recommendations was higher in Portugal and Spain, in these countries cereal ingestion was higher than in Latin-America. PA was higher in Portugal and Spain than in Latin-America (Table 2).

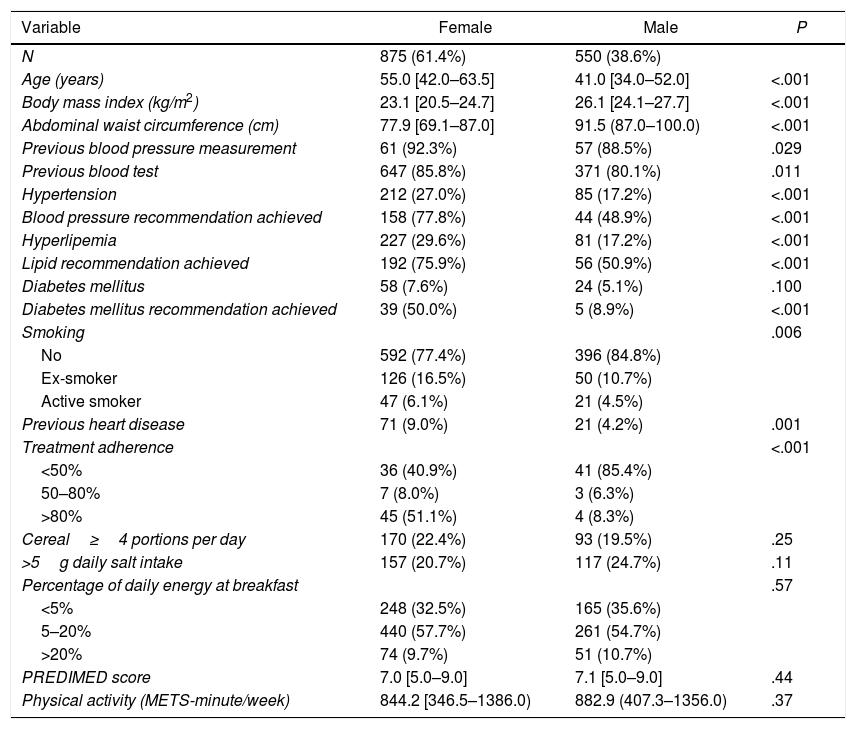

Comparison between gendersThe differences between genders were reported in Table 3. The number of women who responded the survey was higher than the number of men. Women were older than men (median age 55.0 [IQR, 42.0–63.5] years and 41.0 [IQR, 34.0–52.0] years, respectively, P<.001), and had a higher prevalence of CVRF. Although more women achieved CVRF goals than men, active smoking was more common in women. The nutritional parameters and the level of PA were similar between genders (Table 3).

Comparison between gender.

| Variable | Female | Male | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 875 (61.4%) | 550 (38.6%) | |

| Age (years) | 55.0 [42.0–63.5] | 41.0 [34.0–52.0] | <.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.1 [20.5–24.7] | 26.1 [24.1–27.7] | <.001 |

| Abdominal waist circumference (cm) | 77.9 [69.1–87.0] | 91.5 (87.0–100.0) | <.001 |

| Previous blood pressure measurement | 61 (92.3%) | 57 (88.5%) | .029 |

| Previous blood test | 647 (85.8%) | 371 (80.1%) | .011 |

| Hypertension | 212 (27.0%) | 85 (17.2%) | <.001 |

| Blood pressure recommendation achieved | 158 (77.8%) | 44 (48.9%) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipemia | 227 (29.6%) | 81 (17.2%) | <.001 |

| Lipid recommendation achieved | 192 (75.9%) | 56 (50.9%) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 58 (7.6%) | 24 (5.1%) | .100 |

| Diabetes mellitus recommendation achieved | 39 (50.0%) | 5 (8.9%) | <.001 |

| Smoking | .006 | ||

| No | 592 (77.4%) | 396 (84.8%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 126 (16.5%) | 50 (10.7%) | |

| Active smoker | 47 (6.1%) | 21 (4.5%) | |

| Previous heart disease | 71 (9.0%) | 21 (4.2%) | .001 |

| Treatment adherence | <.001 | ||

| <50% | 36 (40.9%) | 41 (85.4%) | |

| 50–80% | 7 (8.0%) | 3 (6.3%) | |

| >80% | 45 (51.1%) | 4 (8.3%) | |

| Cereal≥4 portions per day | 170 (22.4%) | 93 (19.5%) | .25 |

| >5g daily salt intake | 157 (20.7%) | 117 (24.7%) | .11 |

| Percentage of daily energy at breakfast | .57 | ||

| <5% | 248 (32.5%) | 165 (35.6%) | |

| 5–20% | 440 (57.7%) | 261 (54.7%) | |

| >20% | 74 (9.7%) | 51 (10.7%) | |

| PREDIMED score | 7.0 [5.0–9.0] | 7.1 [5.0–9.0] | .44 |

| Physical activity (METS-minute/week) | 844.2 [346.5–1386.0) | 882.9 (407.3–1356.0) | .37 |

Data are expressed as no. (%) or median [interquartile range].

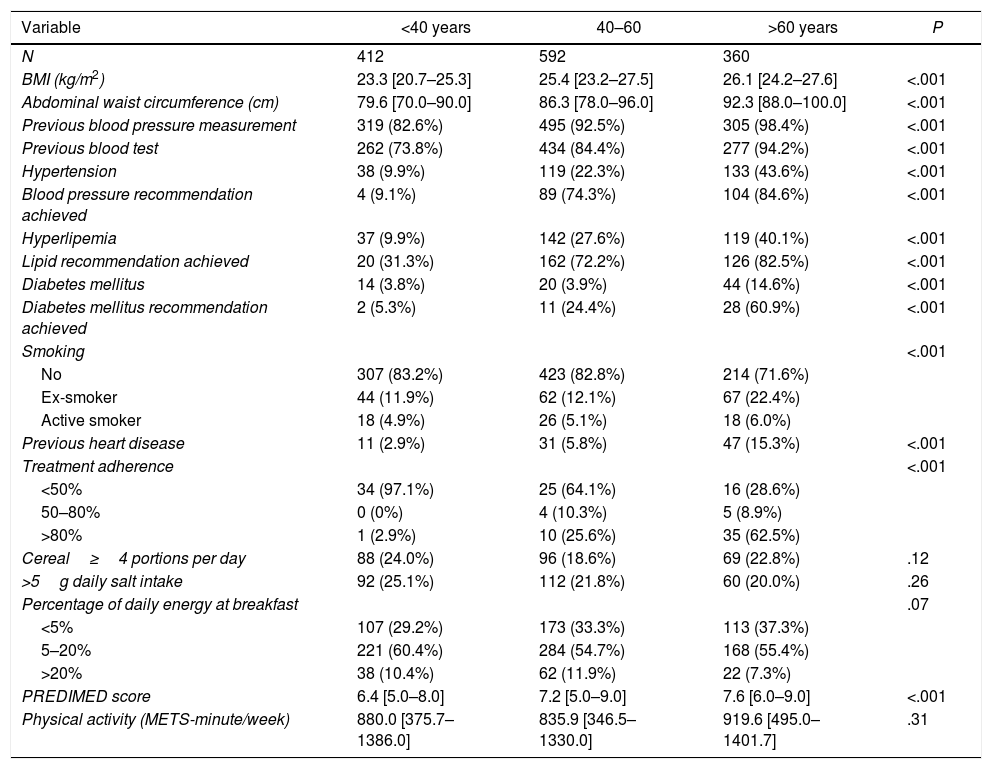

A total of 1364 participants notified their age. To analyze the difference according to age, they were divided into 3 groups as described in Table 4.

Comparison between age group.

| Variable | <40 years | 40–60 | >60 years | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 412 | 592 | 360 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 [20.7–25.3] | 25.4 [23.2–27.5] | 26.1 [24.2–27.6] | <.001 |

| Abdominal waist circumference (cm) | 79.6 [70.0–90.0] | 86.3 [78.0–96.0] | 92.3 [88.0–100.0] | <.001 |

| Previous blood pressure measurement | 319 (82.6%) | 495 (92.5%) | 305 (98.4%) | <.001 |

| Previous blood test | 262 (73.8%) | 434 (84.4%) | 277 (94.2%) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 38 (9.9%) | 119 (22.3%) | 133 (43.6%) | <.001 |

| Blood pressure recommendation achieved | 4 (9.1%) | 89 (74.3%) | 104 (84.6%) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipemia | 37 (9.9%) | 142 (27.6%) | 119 (40.1%) | <.001 |

| Lipid recommendation achieved | 20 (31.3%) | 162 (72.2%) | 126 (82.5%) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (3.8%) | 20 (3.9%) | 44 (14.6%) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus recommendation achieved | 2 (5.3%) | 11 (24.4%) | 28 (60.9%) | <.001 |

| Smoking | <.001 | |||

| No | 307 (83.2%) | 423 (82.8%) | 214 (71.6%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 44 (11.9%) | 62 (12.1%) | 67 (22.4%) | |

| Active smoker | 18 (4.9%) | 26 (5.1%) | 18 (6.0%) | |

| Previous heart disease | 11 (2.9%) | 31 (5.8%) | 47 (15.3%) | <.001 |

| Treatment adherence | <.001 | |||

| <50% | 34 (97.1%) | 25 (64.1%) | 16 (28.6%) | |

| 50–80% | 0 (0%) | 4 (10.3%) | 5 (8.9%) | |

| >80% | 1 (2.9%) | 10 (25.6%) | 35 (62.5%) | |

| Cereal≥4 portions per day | 88 (24.0%) | 96 (18.6%) | 69 (22.8%) | .12 |

| >5g daily salt intake | 92 (25.1%) | 112 (21.8%) | 60 (20.0%) | .26 |

| Percentage of daily energy at breakfast | .07 | |||

| <5% | 107 (29.2%) | 173 (33.3%) | 113 (37.3%) | |

| 5–20% | 221 (60.4%) | 284 (54.7%) | 168 (55.4%) | |

| >20% | 38 (10.4%) | 62 (11.9%) | 22 (7.3%) | |

| PREDIMED score | 6.4 [5.0–8.0] | 7.2 [5.0–9.0] | 7.6 [6.0–9.0] | <.001 |

| Physical activity (METS-minute/week) | 880.0 [375.7–1386.0] | 835.9 [346.5–1330.0] | 919.6 [495.0–1401.7] | .31 |

Data are expressed as no. (%) or median [interquartile range].

Those physicians under 40 years reported the lowest prevalence of CVRF. Those physicians aged 60 years or more, had the highest prevalence of CVRF, abdominal waist circumference and BMI. Active smoking was higher in the middle-aged group, those between 40 and 60 years. The lowest level of adherence to treatment was reported in the youngest group, and the highest adherence was reached in the oldest group. The youngest group was the one with the lowest adherence to Mediterranean diet (Table 4). Analyzing the most relevant parameters, the consumption of olive oil in the different age groups is low, in general, 1–2 tablespoons per day. The consumption of >4 tablespoons per day of olive oil is present in approximately 10% of the analyzed sample, mainly in the age group between 40 and 60 years. Mean intake of vegetables and fruits is between 1 and 2 pieces each day. Likewise, the ingestion of fruits and vegetables is lower than the recommendations that physicians use to give in daily practice.

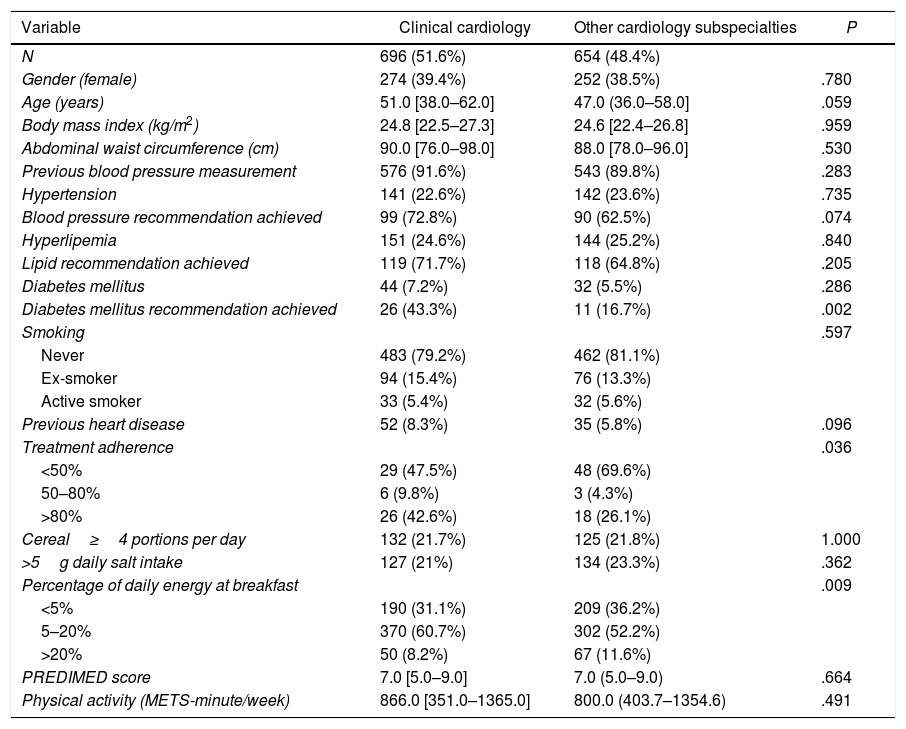

Comparison between clinical cardiology versus other subspecialtiesClinical cardiology was the most frequent responder subspecialty. Compared with other subspecialties, clinical cardiologists achieved more frequently DM goals, showed a higher treatment adherence and had more commonly a daily energy intake at breakfast between 5% and 20% (Table 5).

Comparing between clinical cardiology versus other subspecialties.

| Variable | Clinical cardiology | Other cardiology subspecialties | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 696 (51.6%) | 654 (48.4%) | |

| Gender (female) | 274 (39.4%) | 252 (38.5%) | .780 |

| Age (years) | 51.0 [38.0–62.0] | 47.0 (36.0–58.0] | .059 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.8 [22.5–27.3] | 24.6 [22.4–26.8] | .959 |

| Abdominal waist circumference (cm) | 90.0 [76.0–98.0] | 88.0 [78.0–96.0] | .530 |

| Previous blood pressure measurement | 576 (91.6%) | 543 (89.8%) | .283 |

| Hypertension | 141 (22.6%) | 142 (23.6%) | .735 |

| Blood pressure recommendation achieved | 99 (72.8%) | 90 (62.5%) | .074 |

| Hyperlipemia | 151 (24.6%) | 144 (25.2%) | .840 |

| Lipid recommendation achieved | 119 (71.7%) | 118 (64.8%) | .205 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (7.2%) | 32 (5.5%) | .286 |

| Diabetes mellitus recommendation achieved | 26 (43.3%) | 11 (16.7%) | .002 |

| Smoking | .597 | ||

| Never | 483 (79.2%) | 462 (81.1%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 94 (15.4%) | 76 (13.3%) | |

| Active smoker | 33 (5.4%) | 32 (5.6%) | |

| Previous heart disease | 52 (8.3%) | 35 (5.8%) | .096 |

| Treatment adherence | .036 | ||

| <50% | 29 (47.5%) | 48 (69.6%) | |

| 50–80% | 6 (9.8%) | 3 (4.3%) | |

| >80% | 26 (42.6%) | 18 (26.1%) | |

| Cereal≥4 portions per day | 132 (21.7%) | 125 (21.8%) | 1.000 |

| >5g daily salt intake | 127 (21%) | 134 (23.3%) | .362 |

| Percentage of daily energy at breakfast | .009 | ||

| <5% | 190 (31.1%) | 209 (36.2%) | |

| 5–20% | 370 (60.7%) | 302 (52.2%) | |

| >20% | 50 (8.2%) | 67 (11.6%) | |

| PREDIMED score | 7.0 [5.0–9.0] | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | .664 |

| Physical activity (METS-minute/week) | 866.0 [351.0–1365.0] | 800.0 (403.7–1354.6) | .491 |

Data are expressed as no. (%) or median [interquartile range].

To the best of our knowledge, this study provided the first approach to assess lifestyle and cardiovascular habits of cardiologists from Spain, Portugal, and Latin-America. In this study, a significant number of valid responses were obtained. This means that our results may show a reliable depiction of CVRF, lifestyle, and cardiovascular treatment adherence of cardiologists from different countries on different continents.

Healthy lifestyles have been found to have a positive impact on quality of life and even life expectancy.6 The strategy of prevention, according to Geoffrey Rose paradigm “a large number of people at small risk may give rise to more cases of disease than the small number who are at a high risk”7 could address cardiovascular health over the entire life course and reduce health disparities. Individual behavior is influenced by different factors such as familiar lifestyle, ethnic and cultural grouping, workplace and policy of the state and global levels. It is important to point out the crucial role of health care physicians in encouraging evidence-based population-level interventions.8 If the physicians are really convinced about the benefit of preventive strategies, especially dietary habits and PA, they could have a more convincing attitude when transmitting healthy messages to their patients. In the same way, physicians who are adherent to their own treatment could be more convincing when transmitting messages to their patients about the benefits of adequate therapeutic adherence.

Diet is a potent determinant of CVRF such as hypertension, obesity, DM, hyperlipidemia and overall cardiovascular health.9 A recent systematic review positioned the Mediterranean diet as the most likely dietary model to provide protection against coronary heart disease.10 The PREDIMED study showed an absolute risk reduction on cardiovascular events in primary prevention when implementing healthy dietary recommendations.11 In another work, the questionnaire of adherence to the Mediterranean diet of 14 items (MEDAS-14) was validated.12 In the present study, the PREDIMED score was used to know the physicians’ adherence to Mediterranean diet, finding a low adherence.3 Despite a statistically significant difference was found when comparing Spain and Portugal with Latin-America, all of them reported a low adherence to Mediterranean diet. No difference between genders was found. Of note, when comparisons between age groups were analyzed, the group with the lowest adherence to the Mediterranean diet was the youngest one. An explanation for this finding may be the perception of having a low cardiovascular risk and a healthy status when belonging to a younger age group.

The European guidelines for cardiovascular risk prevention recommend <5g salt intake per day.6 In our survey, almost 80% of the population followed the recommendation. Recently, the PESA study4 showed that skipping breakfast was associated with an increase of prevalent noncoronary and generalized atherosclerosis. Comparing both studies, the PESA study reported a <5% consumption of total daily energy at breakfast in 3% of their population,4 while in our population, this number reached 33.2%. These results could make us reconsider the importance of regular breakfast and its relation with primary cardiovascular prevention.

One of the mainstays in cardiovascular prevention is PA. Regular physical exercise decreases all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.13 Physicians must warn against inactivity and help patients to introduce PA to daily life. The European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention, recommend moderate or vigorous aerobic exercise.6 When PA practicing by the physicians was analyzed using the international PA questionnaire,5 our results showed a moderate activity when the whole population was analyzed. Although there was a statistically significant difference related to greater PA in Spain and Portugal compared with Latin-America, it did not reach the level of vigorous PA in any case, no difference was found between gender neither by age.

Even physicians know smoking is one of the main CVRF associated with coronary disease, 5.5% of the responders were active smokers, this data is probably under-reported, smoking is more prevalent, this could suggest a selection bias. When the differences between Spain and Portugal, and Latin-America were analyzed, active smoking was more frequent in Spain and Portugal. Surprisingly, active smoking was more frequent in women. This finding could be explained because of a lower rate of active smoking male responders or because of a progressive increase of active smoking in women. It is interesting to analyze the different age groups because it was observed an increase in active smoking prevalence in the oldest group, possibly because younger physicians are more aware of the importance of quitting smoking, which can be translated into better recommendations for the patients.

Focusing on the most important differences found between Spain, Portugal, and Latin-America, it should be noted that the youngest physicians were more common from European countries and women from Latin-America which can be related to the interest in cardiovascular prevention. Population in Latin-America had a higher BMI as can be seen in Fig. 2, reflecting the highest rate of overweight in those countries compared to the European countries analyzed. Despite the higher prevalence of hypertension and hyperlipidemia in Latin-America, more physicians in Latin-America reported to achieved CVRF goals. Another interesting fact is that treatment adherence was higher in Latin-America.

Regarding the most important differences between genders, women were older than men. This fact would explain the higher prevalence of CVRF. Nevertheless, they had a lower BMI and greater adherence to the treatment compared to men. This could move us to think that female cardiologists could provide to their patients with better advice to improve their cardiovascular health than male cardiologists.

There were few differences between clinical cardiologists and the other subspecialties, suggesting that awareness about CVRF and healthy lifestyle habits was independent of the specialty.

Only 2 surveys with similar characteristics have been published, but both are limited to only one country. Thus, Faggiano et al.,14 analyzed a sample of Italian cardiologists. From the enrolled patients, women represented 26.5%, mean age was 52.7 years and 74% of the responders were clinical cardiologists. Active smokers were 12.4%. The prevalence of hypertension was 23.3%, DM 3.2%, and hyperlipidemia 35%. Only 5.2% had a previous cardiovascular event, 45% of the population practiced moderate PA and 83% followed Mediterranean diet. With these results, authors concluded that cardiovascular profile of Italian cardiologists may not be considered as ideal or even favorable according to guidelines recommendations. On the other hand, Abuissa et al.,15 analyzed a sample of United States cardiologists. Women represented 7.1% of the whole sample, the mean age was 48 years and 1.3% were active smokers. Prevalence of hypertension was 14%, DM 0.6%, hyperlipidemia 28%, and 4% had a previous coronary event. Authors concluded that cardiologists appear to follow healthier lifestyles than the general adult United States population. Compared with our results, we found a greater representation of women, although the median age was similar. Similar to Faggiano et al.14 our study showed a greater participation of clinical cardiologists (55%). Hypertension prevalence was similar to the Italian population, DM prevalence was higher than the other surveys, hyperlipidemia prevalence was lower, and previous heart disease was more common (7.3%). Surprisingly, Abuissa et al.15 population had a lower percentage of CVRF.

An interesting concept is the “Cardiovascular health” defined by the presence of ideal health behaviors (non-smoking, BMI<25kg/m2, PA at goal levels, and pursuit of a diet consistent with current guideline recommendations) and ideal health factors (untreated total cholesterol<200mg/dL, untreated blood pressure<120/<80mmHg, and fasting blood glucose<100mg/dL).16 When we translate this concept to the survey, only 62 (4.22%) participants meet the 7 optimal values of CVRF. Although the results have the limitations of any voluntary survey, they should make us to think about the role that we, as cardiologists, have in conveying the concept of prevention, healthy habits and CVRF, how we apply it to us and the conviction that we are going to apply to our patients.

LimitationsThe most important limitation of this study was the relatively low rate of responders, justified by the wide and heterogeneous population that was the target for this survey and because it was a voluntary participation without economical retribution. This limited response rate could be associated with a selection bias, especially in Latin-American countries. Finally, 11.4% of the total population completed the survey. Of note, another potential bias of this analysis was the fact that the behaviors of these cardiologists, probably more sensitized to cardiovascular prevention, might differ from the responses of those who did not participate in the survey.

ConclusionsDespite the heterogeneity of the sample, this work provided the first data regarding CVRF, lifestyle and cardiovascular treatment adherence of cardiologists in Latin-America, Portugal, and Spain. Cardiologists were relatively aware of the importance of controlling CVRF although there is more room for improvement. Some differences were found between participants from both sides of the Atlantic. Adopting a healthy lifestyle should be the first step for cardiologists to ensure a greater success on their patients and, consequently, in the whole population.

- -

It is well known that a healthy lifestyle, CVRF adequate control, and therapeutic adherence are the main pieces to reduce the morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular diseases

- -

These are premises that we, as cardiologists, try to transmit to our patients in our daily work.

- -

It is not well known how the cardiologists in Latin-America, Portugal, and Spain carry out these habits in their own life.

- -

Our work provides the first data regarding CVRF, lifestyle and cardiovascular treatment adherence of cardiologist in Latin-America, Portugal, and Spain.

- -

Cardiologists are relatively aware of the importance of controlling CVRF.

- -

Nevertheless, there is more room to improve healthy habits.

Sección de Cardiología Clínica de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.