Given the importance of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in the world, and the fact that in Spain only 2–3% of the population can benefit from access to cardiac rehabilitation programs, the aim of this study is to consider the measurement of quality of life as a good indicator to determine the effectiveness of these programs. This longitudinal study evaluates the impact of a cardiac rehabilitation program on quality of life in a cohort of 181 patients at a Spanish hospital for 2 years.

MethodsQuality of life was assessed at four time points: on admission to the program, at discharge after 12 weeks, and at the 4- and 12-month revisions.

ResultsThe results show an increase in the perception of quality of life compared to the initial situation of the patients at the time of admission to the rehabilitation program, with positive results being observed in practically all the domains of the questionnaire, obtaining a higher score in the physical role domain.

ConclusionsThis study shows that attendance at a cardiac rehabilitation program significantly improves self-perception of health, both physical and emotional.

Dada la importancia de las enfermedades cardiovasculares, primera causa de muerte en el mundo, y que en España solo el 2-3% de la población puede beneficiarse del acceso a programas de rehabilitación cardiaca, el objetivo de este estudio es considerar la medición de la calidad de vida como un buen indicador para determinar la efectividad de estos programas. Este estudio longitudinal evalúa el impacto de un programa de rehabilitación cardiaca sobre la calidad de vida en una cohorte de 181 pacientes de un hospital español durante 2 años.

MétodosLa calidad de vida se evaluó en 4 momentos: al ingreso en el programa, al alta tras 12 semanas, y en las revisiones a los 4 y 12 meses.

ResultadosLos resultados muestran un incremento en la percepción de la calidad de vida respecto a la situación inicial de los pacientes en el momento del ingreso en el programa de rehabilitación, y se observaron resultados positivos en prácticamente todos los dominios del cuestionario; la mayor puntuación se obtuvo en el dominio de rol físico.

ConclusionesEste estudio muestra que la asistencia a un programa de rehabilitación cardiaca mejora significativamente la autopercepción de la salud, tanto física como emocional.

Although mortality rates have decreased in developed countries, cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death. Hence, the need for further research to understand the causes, risk factors, and predictors of heart disease.1

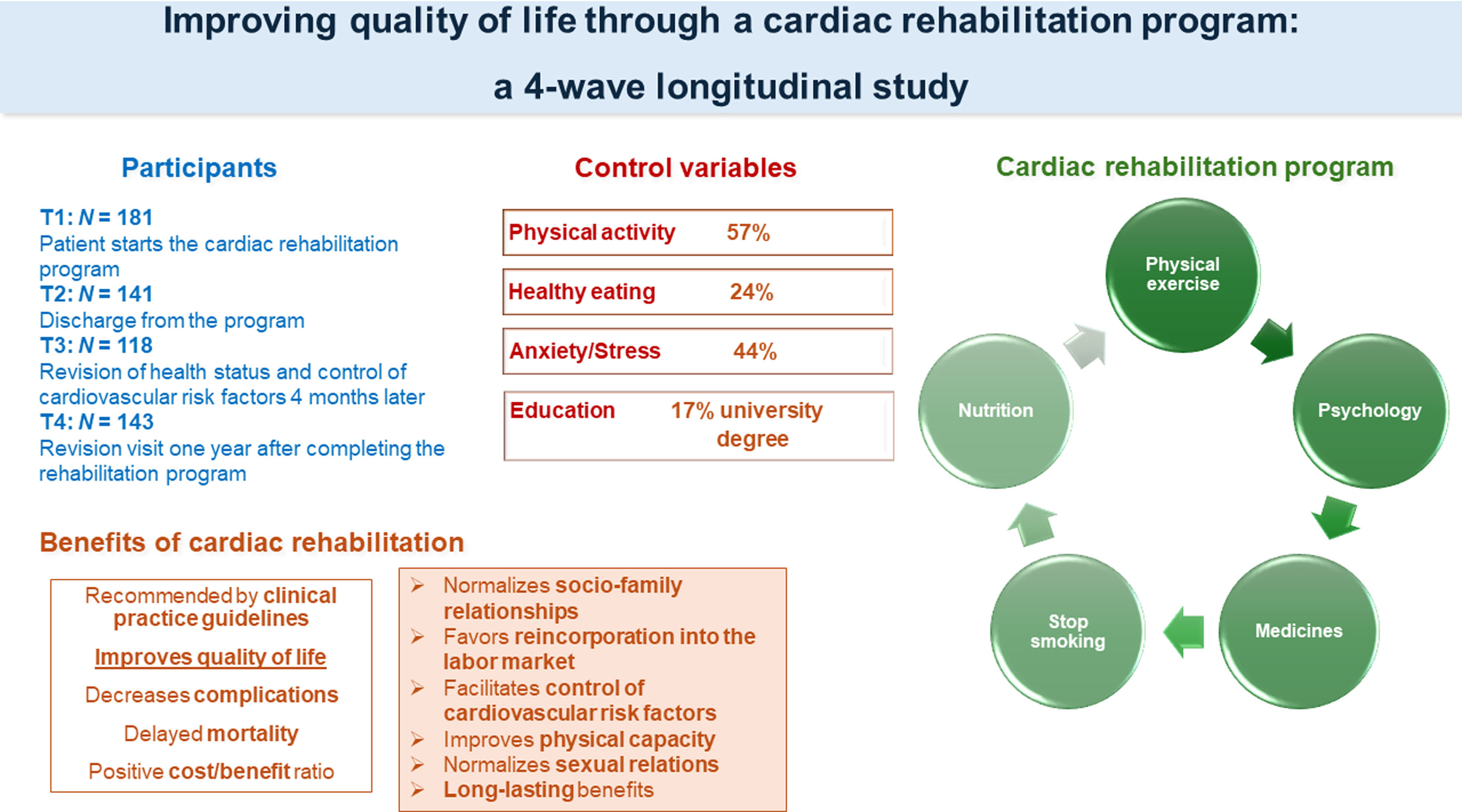

Cardiac rehabilitation programs aim to reduce the physical and psychological consequences that a coronary event causes, to control symptoms, to promote psychosocial well-being, and to facilitate the return-to-work life by reducing the possibility of a new event.2 Cardiac rehabilitation is not only associated with a decrease in morbimortality and disability, but also with an increase in quality of life and a reduction in the number of hospitalizations, so this is a cost-effective therapeutic measure.3

The aim of the present work is to measure the impact of a cardiac rehabilitation program on the quality of life of patients with heart disease in the short and long term, assessing adherence to the program over four time points. In this way, this work contributes to determine the measurement of quality of life as an indicator of rehabilitation efficacy.

MethodsIn cardiac rehabilitation programs health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is considered a subjective assessment. HRQoL relates to how the disease affects the patients’ life and is very useful for planning future care, as it is predictive of response to treatment and also facilitates decision-making.4 Nevertheless, a series of symptoms that influence quality of life and accompany people who have recently suffered a coronary event should be noted. Patients usually refer decreased endurance when walking or climbing stairs, increased dyspnea, or feeling short of breath during physical activity and fatigue. The physical exertion and emotional stress to which they are subjected is sometimes accompanied by chest pain. Any type of physical exercise, the resumption of sexual relations or the return-to-work are cause for anxiety. In many cases, symptoms indicative of depression appear, such as emotional lability, poor quality sleep, and a lack of interest in previously pleasurable activities.5

Although current recommended therapies for coronary artery disease (pharmacological or revascularization by surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention) are very effective in reducing angina symptoms and improving prognosis, patients continue to live with chronic heart disease with potential complications, ranging from advanced heart failure to adverse cardiac events and even death.6 Therefore, these patients are still associated with high burdens of morbidity, mortality, readmission rates, and increased cost of care. It becomes essential to develop effective interventions to help patients with coronary artery disease to adequately manage their chronic disease.7 In line with the above literature, the hypothesis 1 is formulated as follows: scores in the quality-of-life domains will increase after participation in the cardiac rehabilitation program, denoting better quality of life.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed and data are collected and stored in a pseudonymized manner. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the law 14/2007 on biomedical research and other applicable regulations. The handling of personal data complied with the provisions of Regulation (EU) 2016/6798 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC.

Variables related to cardiac rehabilitation programsLifestyle interventions are the core components of cardiac rehabilitation programs. These evidence-based interventions include healthy dietary patterns, regular exercise, cessation of toxic habits, weight control, and screening for depression. Therefore, these lifestyle-related variables were considered in the present study.

As the evidence posits, the main health problems are caused by unhealthy lifestyles such as smoking, sedentary lifestyles, and inadequate diet. Weight loss is also associated with improvements in blood pressure7,9 hence the importance of contemplating physical exercise and healthy eating as a strong point in the assessment. Stress, anxiety, and depression are highly prevalent among cardiac patients and predict worse prognoses after a coronary event.10 Family support has been found to be often associated with a decrease in anxiety and depression.11 Physical activity relates to psychological well-being and influence the process of recovery.12 Based on previous literature, the hypothesis 2 is established: the educational level, the stress/anxiety levels, the level of physical activity, and diet of participants in the rehabilitation program will moderate their scores on the quality-of-life domains.

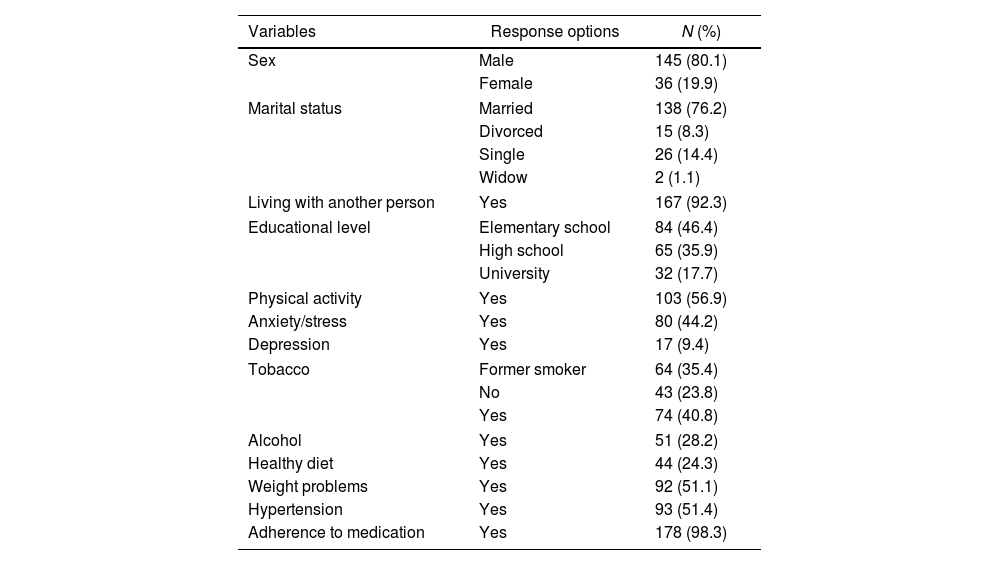

ParticipantsA cohort of 181 patients with heart disease included in the cardiac rehabilitation program at the Lucus Augusti University Hospital in Lugo (Spain) was studied from January 2019 to March 2021. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. There was a clear predominance of male participants (80%). Mean age was 58.5 years (standard deviation, 9.9; range 31–85). Other sociodemographic and control variables relevant to the study of coronary heart disease were also recorded: marital status, educational level, physical activity, healthy diet, toxic habits, anxiety/stress and diagnosis of depression, weight problems, hypertension, and adherence to medication. All participants freely agreed to participate in the study by signing the informed consent form. This study was approved by the regional research ethics committee of Santiago-Lugo (Spain), which ensured the confidentiality of the information.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Variables | Response options | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 145 (80.1) |

| Female | 36 (19.9) | |

| Marital status | Married | 138 (76.2) |

| Divorced | 15 (8.3) | |

| Single | 26 (14.4) | |

| Widow | 2 (1.1) | |

| Living with another person | Yes | 167 (92.3) |

| Educational level | Elementary school | 84 (46.4) |

| High school | 65 (35.9) | |

| University | 32 (17.7) | |

| Physical activity | Yes | 103 (56.9) |

| Anxiety/stress | Yes | 80 (44.2) |

| Depression | Yes | 17 (9.4) |

| Tobacco | Former smoker | 64 (35.4) |

| No | 43 (23.8) | |

| Yes | 74 (40.8) | |

| Alcohol | Yes | 51 (28.2) |

| Healthy diet | Yes | 44 (24.3) |

| Weight problems | Yes | 92 (51.1) |

| Hypertension | Yes | 93 (51.4) |

| Adherence to medication | Yes | 178 (98.3) |

Data are absolute values with percentages in parentheses.

All patients received rehabilitation treatment which consisted of visiting the hospital 2–3 times a week for an estimated 12-weeks period to attend a physical exercise routine, educational talks, and workshops aimed at modifying lifestyles and reducing cardiovascular risk factors. Participation in the cardiac rehabilitation program is standard clinical practice and follows the protocols established at the hospital. The four stages of the study (timepoints [T]; Timepoint 1 [T1] – at admission to the program, Timepoint 2 [T2] – at discharge; Timepoint 3 [T3] – at the 4-month revision; Timepoint 4 [T4] – at the 12-month revision) are described below:

First visitT1, 181 patients: once the patient starts the rehabilitation program after indication by the cardiologist, they are informed about the present study and written informed consent is provided. Then, the SF-36 health questionnaire is administered to assess quality of life. Additionally, demographic and clinical data are collected (Table 1).

Second visitT2, 141 patients: this visit coincides with discharge from the program. Patients complete for an estimated period of 12 weeks, depending on cardiovascular risk and their health profile, an exercise program supervised by a physiotherapist and attendance at educational talks and workshops. Health education provided is focused on the control of cardiovascular risk factors. At the last session, the SF-36 questionnaire is administered again.

Third visitT3, 118 patients: patients are summoned to the hospital 4 months later for a revision of their health status and control of cardiovascular risk factors. They complete the SF-36 questionnaire again.

Fourth visitT4, 143 patients: this is the last planned revision visit one year after completing the cardiac rehabilitation program. Once again, the patient's state of health is monitored, and cardiovascular risk factors are controlled. At this visit, the patient is definitively discharged from the cardiac rehabilitation service and is referred to the general cardiology department for subsequent check-ups. Then, the SF-36 questionnaire is administered.

MeasureAll participants completed the SF-36 questionnaire at four time points: at admission to the program, at discharge and at the 4- and 12-month revisions. The SF-36 Perceived Health Questionnaire13 consists of 36 items measuring eight dimensions of health status: physical function, social function, physical role limitations, emotional role limitations, mental health, vitality, pain and perception of general health. The highest possible score for this questionnaire is 100 and the lowest 0, so that a higher score defines a better health status.

Data analysisNonparametric tests were used for comparisons between individuals (Mann–Whitney test in case of two groups; Kruskal–Wallis test for more than two groups). For paired, intraindividual data comparisons, the paired data version of Student's t-test was used. All analyses were performed with R 3.5.3 statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria).

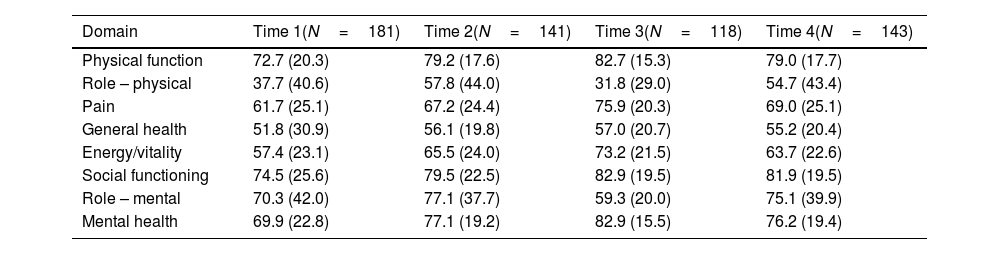

ResultsThe HRQoL domains with the highest scores were physical function, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health (Table 2). Body pain, general health, and vitality showed lower scores. Differences in physical role (linked to problems with work or other daily activities due to physical health) across the four time points may be related to return-to-work and/or adaptation to the job.

Scores for the domains of the SF-36 questionnaire at the four moments.

| Domain | Time 1(N=181) | Time 2(N=141) | Time 3(N=118) | Time 4(N=143) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 72.7 (20.3) | 79.2 (17.6) | 82.7 (15.3) | 79.0 (17.7) |

| Role – physical | 37.7 (40.6) | 57.8 (44.0) | 31.8 (29.0) | 54.7 (43.4) |

| Pain | 61.7 (25.1) | 67.2 (24.4) | 75.9 (20.3) | 69.0 (25.1) |

| General health | 51.8 (30.9) | 56.1 (19.8) | 57.0 (20.7) | 55.2 (20.4) |

| Energy/vitality | 57.4 (23.1) | 65.5 (24.0) | 73.2 (21.5) | 63.7 (22.6) |

| Social functioning | 74.5 (25.6) | 79.5 (22.5) | 82.9 (19.5) | 81.9 (19.5) |

| Role – mental | 70.3 (42.0) | 77.1 (37.7) | 59.3 (20.0) | 75.1 (39.9) |

| Mental health | 69.9 (22.8) | 77.1 (19.2) | 82.9 (15.5) | 76.2 (19.4) |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation.

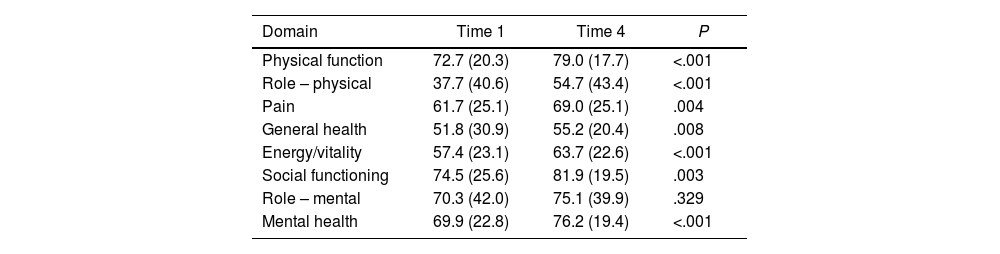

To assess adherence to the rehabilitation program, mean scores were compared between the last data collection and the first visit (Table 3). One year after the end of the program (T4), patients maintained higher scores in all domains compared to the start of cardiac rehabilitation (T1), except for the emotional role dimension (differences were not significant, P=.329).

Domain scores between the first visit (time 1) and the last visit (time 4).

| Domain | Time 1 | Time 4 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 72.7 (20.3) | 79.0 (17.7) | <.001 |

| Role – physical | 37.7 (40.6) | 54.7 (43.4) | <.001 |

| Pain | 61.7 (25.1) | 69.0 (25.1) | .004 |

| General health | 51.8 (30.9) | 55.2 (20.4) | .008 |

| Energy/vitality | 57.4 (23.1) | 63.7 (22.6) | <.001 |

| Social functioning | 74.5 (25.6) | 81.9 (19.5) | .003 |

| Role – mental | 70.3 (42.0) | 75.1 (39.9) | .329 |

| Mental health | 69.9 (22.8) | 76.2 (19.4) | <.001 |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. P-value: Student's t-test for paired data.

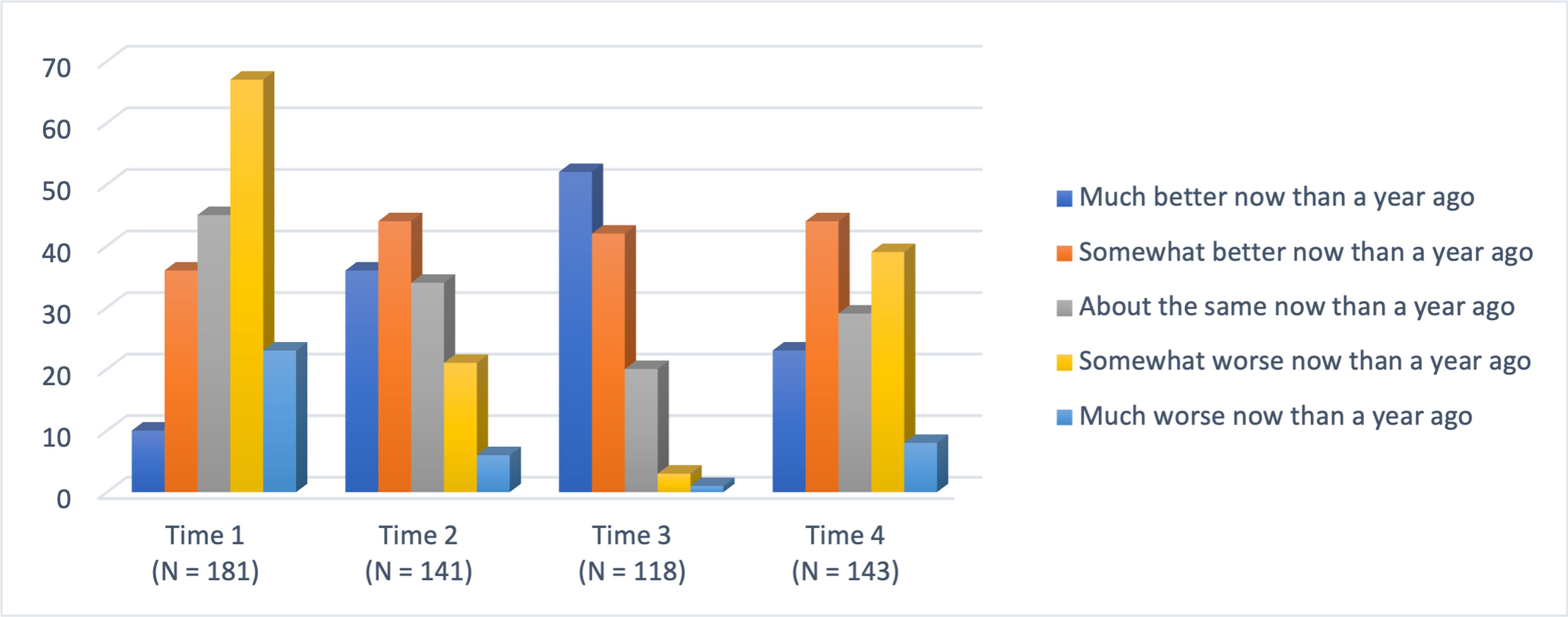

Regarding the transitional domain, scores were increased after the rehabilitation program (Fig. 1). At T1, 37% of the participants considered their health to be worse than it was one year ago. At T2, 31.2% perceived their health to be somewhat better. At T3, 44% of the patients perceived that their health was already much better, and at T4, 30.8% still maintained the perception of their health status as somewhat better.

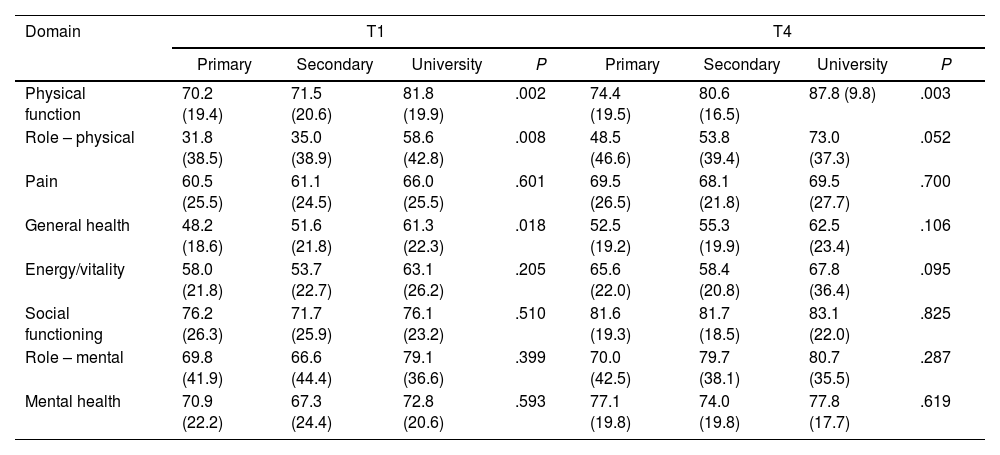

Next, differences were analyzed according to educational level (Table 4). A total of 46.4% of the participants completed primary education, 35.9% finished secondary education, and only 17.7% held a university degree. At T1, significant differences were found in the domains of physical function, physical role, and general health, so that university patients exhibited the highest scores. However, in the domains of social functioning, emotional role, and mental health there seems to be less correlation between the educational level and a better perception of health. At T4, significant differences were only found in the physical function domain (P=.003), so that university participants presented again higher scores. Participants, regardless of their level of education, perceived a significant improvement at T4 with respect to T1 in all domains. These data on educational level are relevant when assessing adherence to rehabilitation programs. As the literature suggests, the lower the educational level, the greater the difficulties in communicating with health professionals. Furthermore, a low level of schooling is associated with disadvantages due to lower income and lack of knowledge of the cardiovascular risk factors that affect their health.14

Scores at the first (T1) and fourth visit (T4) according to educational level.

| Domain | T1 | T4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | University | P | Primary | Secondary | University | P | |

| Physical function | 70.2 (19.4) | 71.5 (20.6) | 81.8 (19.9) | .002 | 74.4 (19.5) | 80.6 (16.5) | 87.8 (9.8) | .003 |

| Role – physical | 31.8 (38.5) | 35.0 (38.9) | 58.6 (42.8) | .008 | 48.5 (46.6) | 53.8 (39.4) | 73.0 (37.3) | .052 |

| Pain | 60.5 (25.5) | 61.1 (24.5) | 66.0 (25.5) | .601 | 69.5 (26.5) | 68.1 (21.8) | 69.5 (27.7) | .700 |

| General health | 48.2 (18.6) | 51.6 (21.8) | 61.3 (22.3) | .018 | 52.5 (19.2) | 55.3 (19.9) | 62.5 (23.4) | .106 |

| Energy/vitality | 58.0 (21.8) | 53.7 (22.7) | 63.1 (26.2) | .205 | 65.6 (22.0) | 58.4 (20.8) | 67.8 (36.4) | .095 |

| Social functioning | 76.2 (26.3) | 71.7 (25.9) | 76.1 (23.2) | .510 | 81.6 (19.3) | 81.7 (18.5) | 83.1 (22.0) | .825 |

| Role – mental | 69.8 (41.9) | 66.6 (44.4) | 79.1 (36.6) | .399 | 70.0 (42.5) | 79.7 (38.1) | 80.7 (35.5) | .287 |

| Mental health | 70.9 (22.2) | 67.3 (24.4) | 72.8 (20.6) | .593 | 77.1 (19.8) | 74.0 (19.8) | 77.8 (17.7) | .619 |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. P-value: Kruskal–Wallis's test.

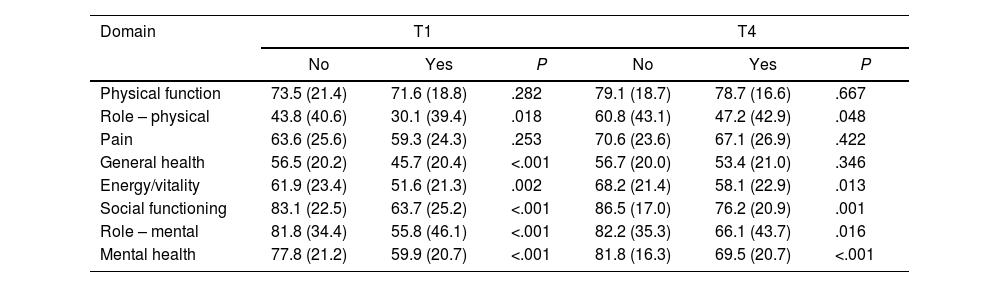

With respect to participants suffering from anxiety/stress (as reported at T1), results show significant differences in all domains, except in physical function and pain (Table 5). Participants who admit to suffering from anxiety/stress (44.2%) showed a worse perception of health. Anxiety and stress have a very significant prevalence in patients with heart disease.15 Emotional lability, lack of interest in what was previously pleasurable, or poor sleep quality are symptoms indicative of deterioration in quality of life. Sometimes the emotional stress to which they are subjected may be accompanied by chest pain, a factor that causes anxiety when having sexual relations or thinking about the future return-to-work.5 At the end of cardiac rehabilitation, this study reveals an improvement in patients’ perception of their health. Results suggest that the cardiac rehabilitation program is particularly beneficial for those who do acknowledge suffering from anxiety and stress problems.

Differences at T1 and T4 for anxiety/stress.

| Domain | T1 | T4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P | No | Yes | P | |

| Physical function | 73.5 (21.4) | 71.6 (18.8) | .282 | 79.1 (18.7) | 78.7 (16.6) | .667 |

| Role – physical | 43.8 (40.6) | 30.1 (39.4) | .018 | 60.8 (43.1) | 47.2 (42.9) | .048 |

| Pain | 63.6 (25.6) | 59.3 (24.3) | .253 | 70.6 (23.6) | 67.1 (26.9) | .422 |

| General health | 56.5 (20.2) | 45.7 (20.4) | <.001 | 56.7 (20.0) | 53.4 (21.0) | .346 |

| Energy/vitality | 61.9 (23.4) | 51.6 (21.3) | .002 | 68.2 (21.4) | 58.1 (22.9) | .013 |

| Social functioning | 83.1 (22.5) | 63.7 (25.2) | <.001 | 86.5 (17.0) | 76.2 (20.9) | .001 |

| Role – mental | 81.8 (34.4) | 55.8 (46.1) | <.001 | 82.2 (35.3) | 66.1 (43.7) | .016 |

| Mental health | 77.8 (21.2) | 59.9 (20.7) | <.001 | 81.8 (16.3) | 69.5 (20.7) | <.001 |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. P-value: Mann–Whitney's test.

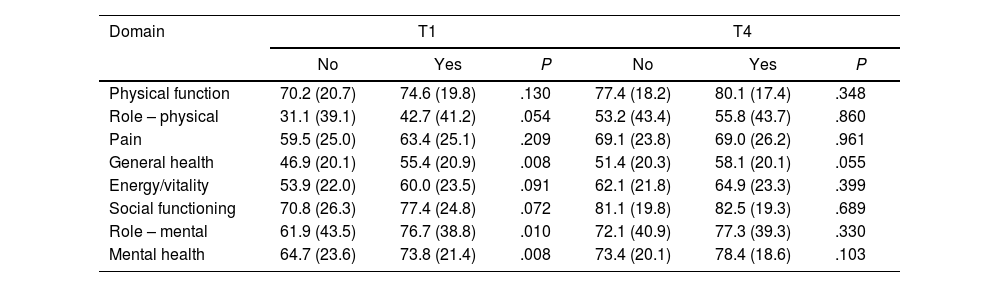

As for physical activity, only 56.9% of the sample admitted to being active. Participants who admitted to being active at T1 obtained higher scores in all domains (Table 6), being differences more striking regarding mental health and general health. At T4 all participants reported higher scores than at T1, regardless of their activity/inactivity. These data confirms that physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles are one of the main health problems in our society, and are in line with previous literature showing that physical activity improves health status, regardless of age, sex, race, or ethnicity.16 Physical inactivity is associated with increased cardiac mortality, whereas exercise, even moderate exercise, is associated with a survival benefit.12

Differences at timepoint 1 and timepoint 4 according to physical activity.

| Domain | T1 | T4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P | No | Yes | P | |

| Physical function | 70.2 (20.7) | 74.6 (19.8) | .130 | 77.4 (18.2) | 80.1 (17.4) | .348 |

| Role – physical | 31.1 (39.1) | 42.7 (41.2) | .054 | 53.2 (43.4) | 55.8 (43.7) | .860 |

| Pain | 59.5 (25.0) | 63.4 (25.1) | .209 | 69.1 (23.8) | 69.0 (26.2) | .961 |

| General health | 46.9 (20.1) | 55.4 (20.9) | .008 | 51.4 (20.3) | 58.1 (20.1) | .055 |

| Energy/vitality | 53.9 (22.0) | 60.0 (23.5) | .091 | 62.1 (21.8) | 64.9 (23.3) | .399 |

| Social functioning | 70.8 (26.3) | 77.4 (24.8) | .072 | 81.1 (19.8) | 82.5 (19.3) | .689 |

| Role – mental | 61.9 (43.5) | 76.7 (38.8) | .010 | 72.1 (40.9) | 77.3 (39.3) | .330 |

| Mental health | 64.7 (23.6) | 73.8 (21.4) | .008 | 73.4 (20.1) | 78.4 (18.6) | .103 |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. P-value: Mann–Whitney's test.

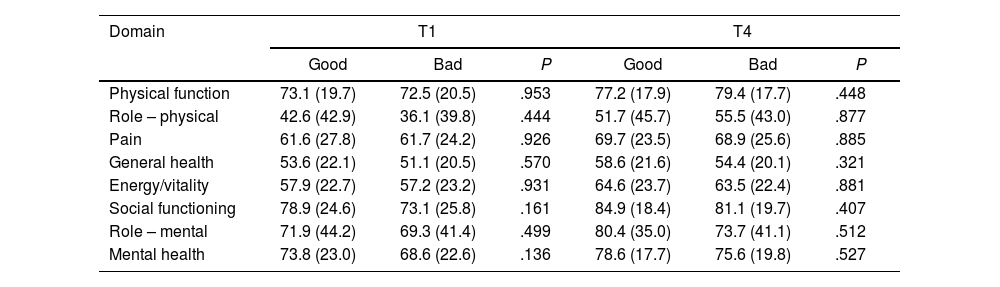

In relation to diet, only 24.3% of the participants admit to eating healthy, which translates into the percentage of poor weight control (51.1%) and high blood pressure (51.4%). Those who admitted to following a healthy diet at T1 obtained higher scores compared to those who did not eat well, particularly in social functioning, mental health, and physical function (Table 7). At T4, all participants, regardless of their diet, managed to increase their scores.

Differences at timepoint 1 and timepoint 4 according to healthy eating.

| Domain | T1 | T4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Bad | P | Good | Bad | P | |

| Physical function | 73.1 (19.7) | 72.5 (20.5) | .953 | 77.2 (17.9) | 79.4 (17.7) | .448 |

| Role – physical | 42.6 (42.9) | 36.1 (39.8) | .444 | 51.7 (45.7) | 55.5 (43.0) | .877 |

| Pain | 61.6 (27.8) | 61.7 (24.2) | .926 | 69.7 (23.5) | 68.9 (25.6) | .885 |

| General health | 53.6 (22.1) | 51.1 (20.5) | .570 | 58.6 (21.6) | 54.4 (20.1) | .321 |

| Energy/vitality | 57.9 (22.7) | 57.2 (23.2) | .931 | 64.6 (23.7) | 63.5 (22.4) | .881 |

| Social functioning | 78.9 (24.6) | 73.1 (25.8) | .161 | 84.9 (18.4) | 81.1 (19.7) | .407 |

| Role – mental | 71.9 (44.2) | 69.3 (41.4) | .499 | 80.4 (35.0) | 73.7 (41.1) | .512 |

| Mental health | 73.8 (23.0) | 68.6 (22.6) | .136 | 78.6 (17.7) | 75.6 (19.8) | .527 |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. P-value: Mann–Whitney's test.

Results show the positive relationship that cardiac rehabilitation has on patients’ perception of health and support that cardiac rehabilitation programs reduce the physical and psychological consequences caused by cardiovascular disease, promoting psychosocial well-being, and reducing the chances of a new event.2,17,18 Regarding the transition domain, the perception of health with respect to one year time, this longitudinal study confirms adherence to what was learned in the cardiac rehabilitation programs, with the participants maintaining this better perception of health. It is necessary to highlight the importance of preventive work to avoid coronary disease. Preventive actions performed by nursing professionals promote health and prevent disease by avoiding the need for acute or rehabilitative care.19 Making prevention a priority is one of the pending issues in medicine,20 since interventions focused on promoting health by reducing cardiovascular risk factors are critical in terms of leading a healthy lifestyle, which determines a 92% and 66% lower risk of coronary heart disease and of presenting clinical manifestations of cardiovascular disease risk factors, respectively.21

Present results show that nearly 1 in 4 patients admit to eating healthy. On the other hand, patients adhere to pharmacological treatment in a 98.3%. These data call for the work that still lies ahead. It is more complicated to change lifestyle than to take the prescribed medication. The study also shows the percentage of participants who continue to smoke (40.8%) after suffering a coronary event. The evidence suggests that more than half of the reduction in cardiovascular mortality has been attributed especially to the reduction in blood pressure, cholesterolemia, and smoking, a favorable trend counterbalanced by the increase in obesity and type 2 diabetes.22 These findings highlight once again the need to reinforce in educational talks the importance of not seeing medication as either the only or the best part of treatment. All self-care interventions aimed at empowering patients to improve the control of their health status become essential in order not to put their health and consequently their quality of life at risk as suggested by the literature consulted.18

From a gender perspective, the incidence rate of coronary heart disease is higher in men than in women, and female participation in rehabilitation programs is low. In the study, only 19.9% of the participants were women. Gender roles are related to women as caregiver and dependent on the household. Additionally, insecurity or lack of previous experience with exercise or limited cultural support for leading a physically active lifestyle has been appointed in the literature.23 Another important aspect is feeling accompanied (92.3%). Patients who do not feel alone find more help when considering lifestyle reforms and coping with the disease.24

Another finding of this study is the importance of health check-ups as reinforcement of what has been learned in terms of cardiovascular risk factors. It is very common for patients to find no time for exercise when they start working and their diet is once again improvised, making use of fast food, something that has repercussions on their blood pressure, body weight and analytical data. Results show a decrease in the scores at the 4-month revision (T3) in both the physical and emotional roles, figures that went up again at the next revision (T4). This suggests the relevance of educational reinforcement in terms of control of risk factors and/or medication adjustments. Therefore, the measurement of quality of life has a high relevance since the evolution of improvement in the physical, social, and emotional role increases patients’ adherence to drug therapy, clinical controls, and a healthy lifestyle, including exercise (Fig. 2).25

Due to travel, return-to-work, decompensation of their disease and, to a greater extent, the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of surveys collected could not be consolidated at all times (T1: N=181; T2: N=141; T3: N=118; T4: N=143). The integration of data from different hospitals is recommended in future studies, which could help to increase the number of participants and improve conclusions and follow-up. In addition, it is recommended to have an equivalent control group and to randomly assign participants to each of the conditions (intervention and control). For ethical reasons, it would be necessary after the study to offer the rehabilitation program to the patients assigned to the control group. This was not possible in the present study because of the sample size and the dropout of participants throughout the study. Another important limitation is the length of the SF-36 questionnaire. When dealing with patients who have a poor literacy level, completing the questionnaire is complicated. There are patients who need help to complete it, which may lead to possible interference with response choice.26

Future research could address other influential factors in people's quality of life, such as poor sleep quality, a prognostic factor in coronary heart disease27 or sexual dysfunction.28 Sexuality is negatively affected in patients suffering from heart disease, due to the fear of suffering a new heart attack. Furthermore, not feeling able to talk about their sexual problems with health professionals is an added handicap. Other avenues of research relate to the impact of nurse education on quality of life of patients29 and new studies including patients in telerehabilitation programs.30 Telerehabilitation programs are an effective alternative or complement to cardiac rehabilitation, helping to overcome accessibility problems. Likewise, it is recommended that the impact of cardiac rehabilitation be measured by addressing the gender perspective, since awareness of the impact of cardiovascular disease in women remains suboptimal, as the literature suggests access to screening and primary prevention programs has been lower in women.31

ConclusionsThe results of this study show the positive impact of cardiac rehabilitation on patients’ quality of life. In line with previous publications, patients who attend a cardiac rehabilitation program improve their quality of life, decrease the number of complications, and delay the progression of the disease. Positive influence is not limited to the physical condition, but also extends to the mental and social condition.25

Attendance to these programs translates into improvements in self-management of the disease. Our findings reveal participants’ improvement in all the domains analyzed, so we conclude cardiac rehabilitation is a key factor in their recovery, slowing the progression of the disease and decreasing the likelihood of new cardiovascular events. We believe it is important to emphasize the importance of continuing to work on prevention, since the aging and growth of the world's population is increasing the number of deaths from cardiovascular diseases, with low and middle-income countries facing a growing number of people suffering from cardiovascular diseases at younger ages.32

- –

Cardiac rehabilitation programs aim to reduce the physical and psychological consequences that a coronary event causes, to control symptoms, to promote psychosocial well-being, and to facilitate the return-to-work life by reducing the possibility of a new event.

- –

The measurement of quality of life is a fundamental tool for guiding health intervention strategies by assessing the impact of a disease at the psychosocial level.

- –

The effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation programs has been measured in several studies but there are very few longitudinal ones, consequently this study contributes to the analysis of the role of adherence to these programs over time and shows the positive impact of cardiac rehabilitation on patients’ quality of life.

- –

Attendance to these programs translates into improvements in self-management of the disease. We conclude cardiac rehabilitation is a key factor in their recovery, slowing the progression of the disease and decreasing the likelihood of new cardiovascular events.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the regional research ethics committee of Santiago-Lugo (Spain). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed, and data are collected and stored in a pseudonymized manner. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the law 14/2007 on biomedical research and other applicable regulations. The handling of personal data complied with the provisions of Regulation (EU) 2016/6798 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC.

Statement on the use of artificial intelligenceThis manuscript did not use artificial intelligence for its preparation.

Authors’ contributionsM.J. Ferreira-Díaz participated in conceptualization, coordination of the intervention program at the hospital, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing, review, and editing of the original manuscript. G. Topa participated in the conceptualization, supervision, and writing of the original manuscript. A. Laguía participated in manuscript writing, review, and editing of the original manuscript. This study has been carried out in the framework of the doctoral thesis of M.J. Ferreira-Díaz, supervised by G. Topa and A. Laguía.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

We would like to give special thanks to the participants that took part in the study.