With an ageing population and increasing life expectancy, a growing proportion of patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are octogenarian. However, evidence regarding the best approach to this clinical scenario is scarce. Our aim was to describe the clinical characteristics, therapeutic management, and outcomes of ≥80-year-old patients undergoing coronary angiography (CA) for ACS, compared to younger patients.

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was performed, comparing clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes from all consecutive patients with ACS undergoing CA in a single tertiary centre between 2015 and 2019.

ResultsA total of 377 patients aged ≥80 years and 1363<80 were included. Cardiovascular risk factors, atrial fibrillation and stroke were more prevalent in octogenarians. Revascularisation of culprit lesions was more frequently performed among under-80-year-old patients. Multivessel disease, acute heart failure at admission, new-onset atrial fibrillation, contrast-induced nephropathy, and in-hospital and 1-year mortality were more frequent among the octogenarian group. Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel was the most frequent combination among octogenarians, whereas younger patients were more frequently prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor or prasugrel. No differences regarding significant bleeding complications were observed.

ConclusionsCompared to younger patients, octogenarians undergoing CA for ACS presented a higher prevalence of multivessel disease, complications, and mortality during hospitalisation and at one year follow-up.

Debido al envejecimiento de la población y la mayor esperanza de vida, una proporción creciente de los pacientes con síndrome coronario agudo (SCA) son octogenarios. La evidencia respecto al mejor abordaje de este escenario clínico es escasa. Nuestro objetivo fue describir las características clínicas, el tratamiento y los resultados de los pacientes de 80 años o más tratados con coronariografía por SCA, comparado con los pacientes más jóvenes.

MétodosEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo, que incluye a todos los pacientes con SCA tratados con coronariografía en un único centro terciario entre 2015 y 2019.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 377 pacientes ≥ 80 años y 1.363<80. Los pacientes octogenarios presentaban mayor prevalencia de factores de riesgo cardiovascular, fibrilación auricular e ictus. La revascularización de lesiones culpables fue más frecuente en los pacientes más jóvenes. Entre los octogenarios, se observó mayor frecuencia de enfermedad multivaso, insuficiencia cardiaca aguda, fibrilación auricular de nueva aparición, nefropatía por contraste y mortalidad intrahospitalaria y al año de seguimiento. El tratamiento antiagregante plaquetario doble con clopidogrel fue la combinación más frecuente en estos pacientes, mientras que en los más jóvenes incluía ticagrelor o prasugrel más frecuentemente. No se observaron diferencias en las complicaciones hemorrágicas significativas.

ConclusionesComparado con pacientes más jóvenes, los octogenarios tratados con coronariografía por SCA presentaron mayor prevalencia de enfermedad multivaso, complicaciones y mortalidad durante la hospitalización y el primer año de seguimiento.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is one of the main causes of mortality worldwide and a frequent reason of hospital admission in patients aged 80 years or older,1 who show a higher risk for adverse events than younger patients.2 In recent decades, revascularisation and medical treatment have significantly reduced mortality and morbidity from ACS. However, elderly patients have consistently been under-represented in cardiovascular clinical trials, resulting in a paucity of evidence regarding the management of ACS in this scenario and these patients being less likely to receive therapeutic management according to guidelines.3 Whereas initially advanced age was considered a relative contraindication to invasive treatment of ACS, current cardiovascular practice stands solidly on an early invasive approach for clinically stable elderly patients, even in higher risk subgroups like diabetics,4 typically based on radial access and drug-eluting stents implantation.1,5 However, an apparent dilution of the benefits of an invasive strategy with increasing age has been reported and its efficacy in nonagenarians remains uncertain.1

Furthermore, frailty, and other geriatric conditions unique to this group, together with aspects of relevance to the older patients, such as quality of life, physical function, and independence, must be carefully evaluated due to their influence on care and outcomes.3

The aim of the present study was to describe the clinical characteristics, therapeutic management, and outcomes of patients undergoing coronary angiography (CA) for an ACS aged 80 years or older, in comparison with patients younger than 80.

MethodsThis was a retrospective cohort study that included all consecutive patients diagnosed with ACS undergoing CA, admitted to a single tertiary hospital between January 2015 and December 2019.

ST-segment elevation was defined as 1mm raise in at least 2 contiguous leads of the electrocardiogram for longer than 30min, measured at the J-point, in the absence of left bundle-branch block.6 Besides, non-ST-segment elevation included ST-segment depression, transient ST-segment elevation, T-wave changes or normal repolarisation on electrocardiogram.7 Myocardial infarction was defined by elevation of cardiac troponin values above the reference limit with clinical evidence of myocardial ischaemia by electrocardiogram alterations, compatible regional wall motion abnormalities on imaging techniques or identification of a coronary thrombus by angiography.8

For purposes of comparison, 2 groups were formed, according to patient's age at admission: those aged ≥80 years or older, also called octogenarians, and those under 80 years old.

Data regarding demographics, clinical features, angiographic characteristics, management, and outcomes were retrospectively collected from patients’ electronic and paper medical records and files. A 12-month follow-up was performed, registering the occurrence of new coronary events, stroke, bleeding complications (defined according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium definitions9), and mortality. All data were recorded on a multipurpose database exclusively created for this study. The protocol was approved by the local ethical committee and patients’ informed consent was waived because it involved only analysis of data obtained during standard clinical practice.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables were reported as mean and standard deviation and were compared with Student t test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and differences among them were assessed with a chi-square test or Fisher's exact test when appropriate.

All tests were 2-sided, and differences were considered statistically significant at P values <.050. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata/IC12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

ResultsBaseline characteristicsDuring the study period, a total of 1740 patients were included: 377 patients aged 80 years or older and 1363 under 80 years old.

Mean age of the octogenarian group was significantly higher than the younger group's (84.7 vs 62.5 years; P<.001) as was the proportion of female patients. Likewise, most of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors, except for dyslipidaemia and obesity, were significantly more frequent among the elder patients. History of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, peripheral vascular disease, atrial fibrillation (AF) and stroke were also more prevalent among the former. Conversely, patients under 80 years old had a higher incidence of a family history of early coronary artery disease. No differences concerning a history of previous myocardial infarction were identified. Regarding other medical conditions, the percentage of chronic kidney disease and significant cognitive impairment were significantly more frequent among the octogenarians. Other population's baseline information is summarised in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort according to their age.

| <80 years old (N=1363) | ≥80 years old (N=377) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.5±11.2 | 84.7±3.6 | <.001* |

| Female sex | 304 (22.3) | 138 (36.6) | <.001* |

| Cardiovascular history | |||

| Hypertension | 816 (59.9) | 297 (78.8) | <.001* |

| Diabetes | 378 (27.7) | 134 (35.5) | .003* |

| Dyslipidaemia | 731 (53.6) | 193 (51.2) | .401 |

| Ever smoker | 854 (62.7) | 146 (38.7) | <.001* |

| BMI | 27.7±6.5 | 27.2±10.0 | .448 |

| Family history of early CAD | 75 (5.5) | 3 (0.8) | <.001* |

| Previous MI | 206 (15.1) | 68 (18.0) | .170 |

| Previous PCI | 203 (14.9) | 61 (16.2) | .538 |

| Previous CABG | 44 (3.2) | 32 (8.5) | <.001* |

| Previous valve surgery | 17 (1.3) | 7 (1.9) | .370 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 125 (9.2) | 56 (14.9) | <.001* |

| Stroke | 82 (6.0) | 42 (11.1) | .001* |

| AF | 95 (7.1) | 80 (21.6) | <.001* |

| CHA2DS2VASc | |||

| 0 | 130 (22.3) | 7 (4.3) | <.001* |

| 1 | 129 (22.2) | 5 (3.0) | <.001* |

| 2 | 108 (18.6) | 14 (8.5) | .002* |

| 3 | 96 (16.5) | 33 (20.1) | .278 |

| ≥4 | 119 (20.4) | 105 (64.0) | <.001* |

| Other medical conditions | |||

| CKD | 39 (6.5) | 28 (16.8) | <.001* |

| Liver disease | 46 (3.5) | 8 (2.2) | .213 |

| Moderate/Severe cognitive impairment | 22 (1.7) | 30 (8.2) | <.001* |

| Treatment before the index episode | |||

| Aspirin | 356 (26.9) | 134 (36.8) | <.001* |

| Clopidogrel | 85 (6.4) | 24 (6.6) | .910 |

| Ticagrelor | 6 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | .638 |

| Prasugrel | 15 (1.1) | 7 (1.9) | .548 |

| Oral anticoagulation | 79 (5.8) | 65 (17.2) | <.001* |

| Beta-blockers | 262 (19.8) | 103 (28.3) | .001* |

| ACEI | 567 (42.9) | 187 (51.4) | .004* |

| Statins | 537 (40.6) | 181 (50.0) | .001* |

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtrate rate; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-STEMI (NSTEMI) were the initial presentations in 62.7% and 37.9% of patients within the elder group and 51.9% and 47.9% of the younger group, respectively. Twelve (3.7%) octogenarians and 9 (0.7%) patients from the younger group presented left bundle-branch block at admission (P<.001). myocardial infarction was diagnosed in over 98% of patients from both groups (P=.745).

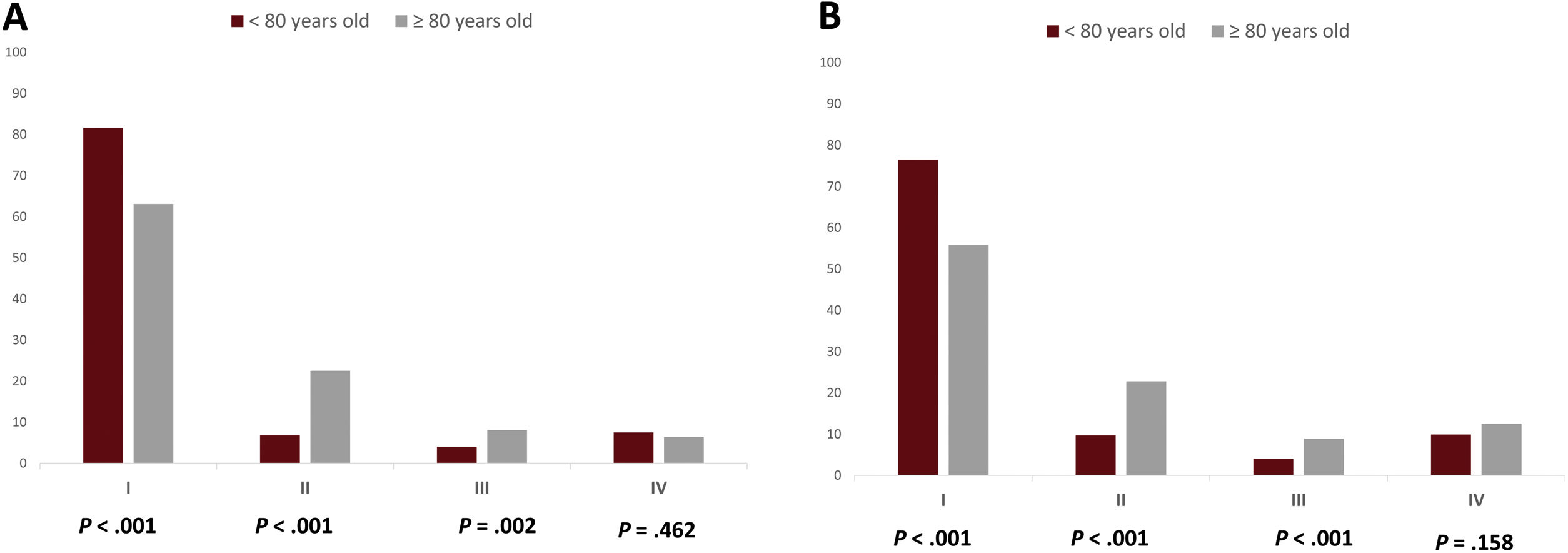

No differences were found regarding haemodynamic status at presentation. However, whereas younger patients more frequently suffered a cardiac arrest before or during CA (8.4% vs 3.3%; P=.001), octogenarians more frequently presented with acute heart failure (Killip–Kimball class II: 22.5% vs 6.8%; P<.001. Killip–Kimball class III: 8.1% vs 4.0%; P=.002) (Fig. 1A). The percentage of patients in both groups presenting with cardiogenic shock and right ventricle infarction did not significantly differ (Table 2).

Index episode characteristics.

| <80 years old | ≥80 years old | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| STEACS | 682 (51.9) | 220 (62.7) | .001b |

| NSTEACS | 629 (47.9) | 131 (37.9) | |

| Systolic aortic pressure (mmHg) | 127.7±26.1 | 128.8±25.8 | .511 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 78.1±18.4 | 78.3±18.7 | .870 |

| Cardiacarresta | 111 (8.4) | 12 (3.3) | .001b |

| Killip–Kimball class at admission | |||

| I | 1063 (81.6) | 227 (63.1) | <.001b |

| II | 89 (6.8) | 81 (22.5) | <.001b |

| III | 52 (4.0) | 29 (8.1) | .002b |

| IV | 98 (7.5) | 23 (6.4) | .462 |

| LVEF (%) | |||

| ≥50% | 315 (54.7) | 81 (49.7) | .098 |

| >40–<50% | 104 (18.1) | 31 (19.0) | .162 |

| >30–≤40% | 86 (14.9) | 24 (14.7) | .170 |

| ≤30% | 71 (12.3) | 26 (16.0) | .079 |

| Mitral regurgitation | |||

| Mild | 157 (27.1) | 55 (33.7) | .040b |

| Moderate | 46 (7.9) | 17 (10.4) | .100 |

| Severe | 11 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) | .152 |

| Aortic stenosis | |||

| Mild | 360 (48.0) | 104 (48.1) | .923 |

| Moderate | 54 (7.2) | 35 (16.2) | <.001b |

| Severe | 38 (5.1) | 23 (10.1) | .011b |

| RV infarction | 51 (3.9) | 14 (3.8) | .976 |

| GRACE score | 138.4±41.4 | 178.9±42.4 | <.001b |

| CRUSADE score | 28.8±16.8 | 41.0±22.2 | <.001b |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.1±3.9 | 12.7±1.8 | <.001b |

| Haematocrit (%) | 42.6±5.7 | 39.0±5.5 | <.001b |

| Platelets (u/dL) | 202517±81529 | 188113±76814 | .003b |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1±0.8 | 1.4±0.7 | <.001b |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 79.7±24.9 | 58.2±22.1 | <.001b |

| Cardiac troponin elevation | 849 (98.3) | 242 (98.4) | .745 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 100±40.0 | 82.3±32.6 | <.001b |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 42.3±13.5 | 42.8±11.6 | .609 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 143.2±100.7 | 107.3±45.2 | <.001b |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AV, atrioventricular; CK, creatine kinase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; NSTACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; RV, right ventricle; STEACS, ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

With respect to echocardiographic findings, no differences in left ventricular ejection fraction at presentation or the presence of significant mitral regurgitation were noted. However, moderate, and severe aortic stenosis were more frequent among the elderly.

Haemoglobin, platelet count and estimated glomerular filtration rate were lower among the elderly patients. GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) and CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) scores were systematically calculated at admission and were significantly higher in the octogenarian group. Other findings from blood analysis at admission are displayed in Table 2.

Regarding antithrombotic treatment at admission, either dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and clopidogrel or single antiplatelet therapy were more frequently used among the elderly patients. Also, DAPT with either ticagrelor or prasugrel were the most common options among the younger group. Anticoagulation was more frequently used among the octogenarians (Table 3).

Treatment at admission for ACS.

| <80 years old | ≥80 years old | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antiplatelet therapy | |||

| Clopidogrel LDa | 892 (66.4) | 287 (76.5) | <.001b |

| Ticagrelor LDa | 315 (23.4) | 54 (14.4) | <.001b |

| Prasugrel LDa | 70 (5.2) | 6 (1.6) | <.001b |

| SAPT | 67 (5.0) | 26 (6.9) | .009b |

| Anticoagulation | |||

| Enoxaparin | 329 (25.7) | 120 (34.4) | .003b |

| Fondaparinux | 154 (12.0) | 44 (12.6) | .585 |

| UFH | 49 (3.8) | 9 (2.6) | .334 |

| Bivalirudin | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | .605 |

| Any | 535 (41.8) | 174 (49.9) | .014b |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 94 (7.4) | 15 (4.3) | .193 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; GP, glycoprotein; LD, loading dose; SAPT, single antiplatelet therapy; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

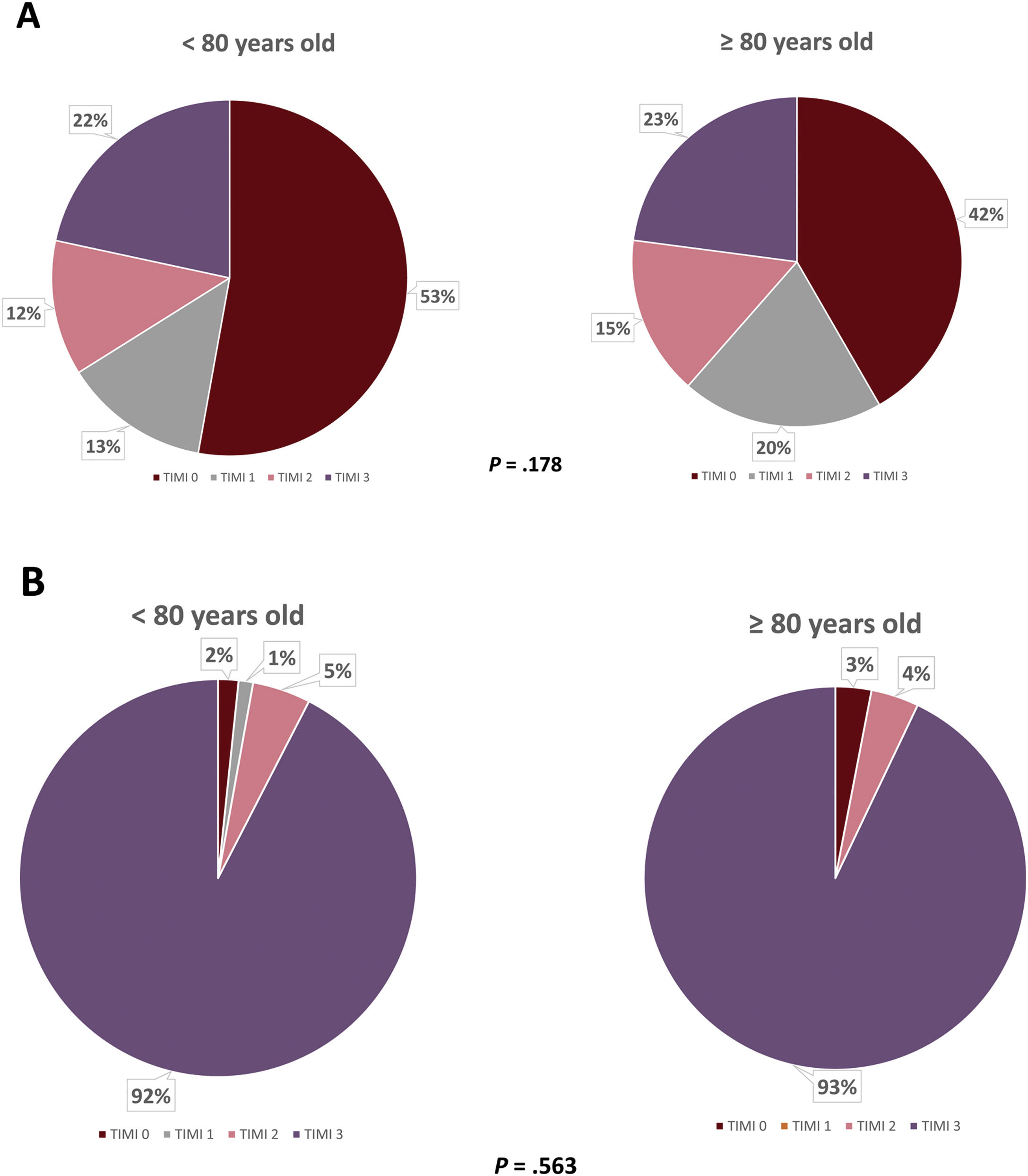

An emergent CA was performed in 42.6% of patients in the under-80-year-old group and in 29.1% of the octogenarians (P<.001) and a culprit lesion was identified in 87.8% and 79.6% of patients, respectively (P<.001). The most frequent location of these lesions was the left anterior descending coronary artery in both groups, followed by the right coronary artery. Revascularisation of the target lesion was achieved in 84.4% of the younger group and 73.3% of the older one (P<.001), predominantly by means of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in both groups. No differences regarding the number of implanted stents per patient or thromboaspiration rates were observed. Information concerning initial and final TIMI flow is displayed in Fig. 2. Regarding revascularisation of non-culprit lesions and timing of such procedure, no differences were observed (Table 4).

Angiographic characteristics.

| <80 years old | ≥80 years old | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary angiography timing | |||

| Emergent | 472 (42.6) | 95 (29.1) | <.001* |

| <24h | 402 (36.3) | 129 (39.4) | .302 |

| 24–72h | 154 (13.9) | 61 (18.7) | .035* |

| >72h | 79 (7.1) | 42 (12.8) | <.001* |

| Radial artery access | 639 (73.0) | 166 (66.7) | .119 |

| Number of diseased vessels | |||

| 0 | 121 (8.9) | 39 (10.3) | .383 |

| 1 | 654 (48.0) | 133 (35.3) | <.001* |

| 2 | 363 (26.6) | 112 (29.7) | .235 |

| 3 | 225 (16.5) | 93 (24.7) | <.001* |

| Identified culprit lesion | 1084 (87.8) | 270 (79.6) | <.001* |

| Culprit vessel distribution | |||

| LM | 22 (2.6) | 8 (3.2) | .565 |

| LAD | 319 (37.2) | 102 (41.3) | .240 |

| Cx | 163 (19.0) | 37 (15.0) | .148 |

| RCA | 267 (31.1) | 61 (24.7) | .052 |

| OMA | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | .517 |

| RI | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | .448 |

| IMA graft | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Saphenous vein graft | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.8) | .184 |

| Revascularisation of culprit lesion | 1142 (84.4) | 275 (73.3) | <.001* |

| CABG | 105 (9.2) | 13 (4.7) | .004* |

| PCI | 1037 (90.8) | 262 (95.3) | |

| Stents (No./patient) | 1.0±0.8 | 0.9±0.9 | .070 |

| Thromboaspiration | 98 (21.0) | 18 (15.9) | .224 |

| Revascularisation of non-culprit lesions | 25 (21.7) | 5 (12.5) | .237 |

| Index procedure | 3 (2.6) | 1 (2.5) | .586 |

| Deferred | 22 (19.1) | 4 (10.0) | .221 |

Cx, circumflex; IMA, internal mammary artery; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LM, left main coronary artery; OMA, obtuse marginal artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary artery; RI, ramus intermedius; RCA, right coronary artery.

Development of congestive heart failure during in-hospital stay was significantly more common among octogenarians compared to the younger group: the proportion of patients developing Killip–Kimball class II was 22.8% vs 9.7% (P<.001) and Killip–Kimball III was 8.9% vs 4.0% (P<.001), respectively (Fig. 1B). Transient atrioventricular block and post-infarction AF were also more frequently observed among the elderly patients, although the occurrence of stroke during admission was similar in both groups. However, no differences were observed regarding the incidence of cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, mechanical complications or the need for vasopressor support, intra-aortic balloon pump implantation or mechanical ventilation (Table 5). The proportion of patients with normal left ventricular ejection fraction at hospital discharge was higher among the younger group; in contrast, the presence of severely reduced systolic ventricular function was more frequent within the octogenarian group. Regarding arterial access-related complications, only haematomas were found to be more frequent among the octogenarians, as were minor bleeding complications, contrast-induced nephropathy (defined as ≥25% increase in serum creatinine within 48–72h following contrast administration) and infections. In-hospital mortality occurred in 12.2% of the elderly group and in 5.1% of the younger one (P<.001), primarily due to cardiovascular causes. Information regarding other complications during admission is summarised in Table 5.

Complications during hospital admission.

| <80 years old | ≥80 years old | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest Killip–Kimball class | |||

| I | 993 (76.4) | 201 (55.8) | <.001* |

| II | 126 (9.7) | 82 (22.8) | <.001* |

| III | 52 (4.0) | 32 (8.9) | <.001* |

| IV | 129 (9.9) | 45 (12.5) | .158 |

| Stent thrombosis | 23 (1.7) | 2 (0.5) | .094 |

| Peri-infarction AF | 96 (7.3) | 41 (11.2) | .015* |

| AV block | |||

| Transient | 79 (5.8) | 34 (9.1) | .025* |

| Permanent | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.5) | .169 |

| Sustained VT | 59 (4.5) | 22 (6.0) | .228 |

| Cardiac arrest | 116 (8.6) | 44 (11.7) | .062 |

| LVEF (%) at hospital discharge | |||

| ≥50% | 840 (65.9) | 196 (56.6) | .002* |

| >40–<50% | 242 (19.0) | 72 (20.8) | .445 |

| >30–≤40% | 71 (5.6) | 21 (6.1) | .721 |

| ≤30% | 122 (9.6) | 57 (16.5) | <.001* |

| Mechanical complications | 8 (1.3) | 3 (2.4) | .716 |

| Postinfarction pericarditis | 16 (2.7) | 2 (1.2) | .257 |

| Stroke | 21 (1.5) | 8 (2.1) | .440 |

| Arterial access-related | |||

| Haematoma | 24 (1.8) | 23 (6.1) | <.001* |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | .873 |

| Fistula | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | .058 |

| Bleeding | |||

| Minor | 32 (2.4) | 21 (5.7) | .001* |

| Major | 15 (1.1) | 6 (1.6) | .445 |

| Life threatening | 11 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | .978 |

| Acute kidney disease | 139 (10.5) | 94 (25.6) | <.001* |

| Contrast-induced nephropathy | 20 (3.2) | 22 (12.4) | <.001* |

| Infection | 112 (8.5) | 72 (19.6) | <.001* |

| Vasopressor support | 95 (15.9) | 22 (12.9) | .366 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 9 (6.3) | 2 (4.1) | .572 |

| Mechanical ventilation necessity | |||

| Non-invasive | 61 (10.1) | 13 (7.6) | .334 |

| Invasive | 34 (5.6) | 6 (3.5) | .273 |

| Hospital admission duration (days) | 8.7±10.9 | 8.9±3.6 | .099 |

| Death | 69 (5.1) | 46 (12.2) | <.001* |

| Cardiovascular cause | 46 (66.6) | 33 (71.7) | .005* |

AV, atrioventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Concerning antithrombotic treatment at hospital discharge, elderly patients were more frequently prescribed clopidogrel as part of their DAPT. Likewise, the percentage of patients receiving anticoagulation was higher among the octogenarians, primarily due to a previous indication (17.1%), followed by new-onset AF (6.8%) and the presence of intraventricular thrombus (0.4%). Furthermore, the under-80-year-old group were more frequently prescribed DAPT comprised of either ticagrelor or prasugrel in combination with aspirin. Data regarding other pharmacological treatment at hospital discharge is shown in Table 6.

Treatment at hospital discharge.

| <80 years old | ≥80 years old | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antiplatelet therapy | |||

| Clopidogrel | 575 (54.9) | 262 (78.2) | <.001* |

| Ticagrelor | 430 (34.3) | 58 (17.3) | <.001* |

| Prasugrel | 229 (18.3) | 5 (1.5) | <.001* |

| SAPT | 18 (1.4) | 10 (3.0) | .056 |

| Anticoagulation | |||

| Acenocumarol | 103 (16.6) | 70 (37.8) | <.001* |

| NOAC | 19 (3.1) | 17 (9.2) | <.001* |

| Other | 8 (1.3) | 2 (1.1) | .820 |

| Lipid-lowering therapy | |||

| Statins | 1185 (95.7) | 298 (93.1) | .053 |

| Ezetimibe | 11 (1.9) | 3 (2.0) | .956 |

| PCSK9 inhibitors | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | .466 |

| Other | |||

| Beta-blockers | 1033 (83.6) | 225 (70.3) | <.001* |

| ACEI | 911 (73.7) | 205 (64.1) | .001* |

| ARB | 48 (9.9) | 23 (20.0) | .003* |

| Sacubitril/valsartan | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | .607 |

| MRA | 19 (14.1) | 5 (10.9) | .580 |

| PPI | 827 (95.5) | 239 (97.2) | .249 |

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; PPI, proton pump inhibitors; SAPT, single antiplatelet therapy.

During the first year following hospital discharge, death occurred more frequently among the elderly group (16.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001), predominantly due to cardiovascular causes. Ischaemic stroke was also more frequent within this group (4.6% vs 2.0%; P=.011). No differences were observed regarding the incidence of a new ACS or bleeding complications. In addition, dose titration of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and statins was more commonly achieved in the younger patients. A higher proportion of younger patients also attended a structured cardiac rehabilitation programme (Table 7).

One year follow-up.

| <80 years old | ≥ 80 years old | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 41 (3.8) | 48 (16.8) | <.001* |

| Cardiovascular cause | 8 (2.1) | 15 (11.7) | <.001* |

| New ACS | 24 (4.5) | 9 (6.4) | .338 |

| Stroke | |||

| Ischaemic | 22 (2.0) | 13 (4.6) | .011* |

| Haemorrhagic | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | .565 |

| Bleeding complications | |||

| Minor | 20 (3.4) | 13 (7.6) | .017* |

| Major | 4 (0.7) | 4 (2.3) | .060 |

| Life threatening | 1 (0.2) | 2 (1.2) | .065 |

| Beta-blockers dose titration | 337 (34.9) | 76 (29.8) | .127 |

| ACEI dose titration | 351 (36.6) | 73 (29.3) | .032* |

| Statins dose titration | 688 (71.1) | 151 (57.6) | <.001* |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 263 (45.8) | 43 (24.7) | <.001* |

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction.

The present study comprises a large series of invasively managed ACS in octogenarian patients, in comparison with those younger than 80 years old. The main findings in octogenarians in this study were as follows: (a) acute heart failure at admission (excluding cardiogenic shock) was more frequent in this group; (b) DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel or single antiplatelet therapy, both at admission and at hospital discharge, were the most commonly used antithrombotic drug options; (c) identification and revascularisation of a culprit lesion was less frequent in this group; (d) new-onset AF and acute kidney disease were more frequent among octogenarians, whereas no differences were observed concerning bleeding complications; and (e) in-hospital and 1 year-mortality rates were higher, mainly due to cardiovascular causes.

Coronary artery disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in older patients.10 With an ageing population and longer life expectancies, a progressively increasing proportion of patients presenting with an ACS are octogenarian.2 However, elderly patients have consistently been under-represented in most clinical trials in the field.11,12

As previously reported,13 in our cohort of octogenarians, classical cardiovascular risk factors were more prevalent than in the younger group, as well as chronic kidney disease,14 AF and stroke.15 Furthermore, other age-related clinical conditions share several predisposing factors with coronary artery disease, such as cognitive impairment or dementia.16

Among octogenarians, the proportion of patients presenting with STEMI (62.7%) was greater than those presenting with NSTEMI (37.9%), in contrast with available literature.17,18 This may be due to a selection bias, as only patients undergoing CA were included in our series. Conversely, even though the absolute number of patients with STEMI increases with age, it represents a smaller proportion of overall ACS admissions in the elderly due to the frequent presence of left bundle-branch block or nondiagnostic electrocardiograms in this population. Thus, in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction, the proportion of patients with ACS and left bundle-branch block or nondiagnostic electrocardiograms increased from 5% and 23% within those <65 years old to 33.8% and 43% for those 85 years or older, respectively.3,11 Compared to these percentages, a smaller proportion of left bundle-branch block (3.7%) was observed among octogenarians included in the present study, most likely due to the previously mentioned selection bias.

Revascularisation of the culprit lesion was performed in 84.4% of patients under 80 years old and 73.3% of the octogenarians (P<.001), differences likely due to a higher prevalence of multivessel disease, calcification, and tortuosity, which have been attributed to advanced age.19

Even though over 90% of the cases in both groups underwent PCI, the proportion of patients who were revascularised with CABG was significantly higher among the younger group. Several studies have compared revascularisation outcomes with either PCI or CABG obtaining conflicting results. Whereas a meta-analysis of 66 studies observed that CABG was associated with higher 30-day and 1-year mortality rates,20 other series have described poorer short and long-term outcomes with PCI21,22 with other studies reporting no significant differences between both techniques with regards to all-cause death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.23 Although CABG more frequently achieves complete revascularisation compared to PCI, with a lower requirement for repeat revascularisation, the less invasive PCI approach may be more appropriate in older patients who are often frail and are more prone to periprocedural CABG complications, including stroke and neurocognitive decline.18 However, no randomised trials of PCI versus CABG solely restricted to an older patient cohort has been performed so far.

Regarding antithrombotic treatment, DAPT including aspirin and clopidogrel was prescribed in 76.5% of the ≥80-year-old group (P<.001), whereas DAPT with ticagrelor or prasugrel was more frequently used in the younger patients. The proportion of octogenarian patients treated with ticagrelor at hospital discharge was 17.3%, in accordance with that reported by LONGEVO study in a similar population.24 According to current guidelines,25 P2Y12 inhibitor selection must be guided by bleeding risk assessment. In fact, advanced age is a greater risk factor for haemorrhagic complications rather than recurrent ischaemic events following revascularisation.18,26 Therefore, in a high bleeding risk scenario, clopidogrel or ticagrelor may be suitable options, considering that the latter is contraindicated in case of previous intracranial haemorrhage, which is a more frequent condition among older patients.27 Moreover, prasugrel is not recommended in patients ≥75 years old, those with a body weight <60kg or with history of intracranial haemorrhage or ischaemic stroke; since it did not demonstrate any clinical benefit compared to clopidogrel in individuals with increased bleeding risk in the TRITON-TIMI 38 Trial.28 However, prasugrel prescription may be considered in selected patients in whom ischaemic risk is particularly high and does not have absolute contraindications.

As previously reported, ACS-related complications increase in frequency with age.29 Regarding STEMI in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction, up to 11.7% of patients <65 years versus 44.6% of those ≥85 years old presented Killip–Kimball class≥II at admission.3 Likewise, among NSTEMI presentations, acute heart failure was present in 15% of those patients ≥75 years vs 6.3% of those <75 years of age.30 In our cohort, a significantly greater proportion of octogenarians, suffered acute heart failure at admission and during hospital stay, together with a higher percentage of patients showing severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction at discharge. Regarding the occurrence of stroke before discharge, we did not observe a significant difference between both groups (1.5% in <80 years vs 2.1% in ≥80 years; P=.440), despite the higher incidence of post-infarction AF among the older group. Similarly, in the After Eighty trial, those patients over 80 years old randomised to early invasive strategy following NSTEMI had a 3% incidence of stroke during their hospital stay.1 However, at one year follow-up a significantly greater occurrence of ischaemic stroke was observed. Concerning other complications, acute kidney disease, particularly contrast-induced nephropathy, was more frequently observed among elderly patients in our study (12.4%), in contrast with a 2% incidence reported by Tegn et al.1 among invasively managed patients with NSTEMI. Such differences are likely due to the octogenarians in our study having a more impaired renal function at admission (baseline creatinine 1.4±0.7mg/dL in our series vs 1.15±0.5mg/dL in the study). With regards to major and life-threatening bleeding complications, we did not observe significant differences between groups, in accordance with some previous reports.1,31 However, other registries have described increased incidence of haemorrhagic complications in nonagenarians, highlighting that the risk-benefit balance must be carefully assessed, particularly at extreme chronological ages.18,32

Mortality in ACS significantly increases with age.18,33 In fact, it has been shown that the probability of in-hospital death rises by 70% for each 10-year increase in age.34 In our cohort, death during admission and after 1 year follow-up was significantly higher among the octogenarians (12.2% vs 5.1%; P<.001 for in-hospital mortality, 16.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001 for mortality at 1-year follow-up). In parallel with our findings, previous registries have reported 10% probability of dying during admission in patients ≥85 years old and up to 25% during the first year.11

In concordance with other previous studies,35,36 octogenarians in our series were less frequently enrolled in cardiac rehabilitation programmes. However, older patients may also benefit from such programmes, regardless of comorbidity status.37 Therefore, age must not be considered in isolation for clinical decision-making regarding ACS treatment in octogenarians, but rather integrated in a patient-centred assessment considering patient's preferences, expected quality of life and life expectancy.3,38

Limitations and strengthsSeveral limitations to this study must be taken into account: (a) all patients included underwent a CA, possibly resulting in selection bias; (b) all cases in which a conservative approach was taken were not included in the study, which prevents the evaluation of outcomes according to management strategy within the octogenarian cohort and the proportion of patients from this group undergoing CA; (c) recruiting patients over a long period of time may explain some differences in treatment modalities; (d) information regarding stent platforms used, intracoronary imaging and coronary physiology assessment, or long-term antithrombotic treatment at one year follow-up was not systematically recorded; and (e) multivariate analyses were not performed because a significant proportion of missing values for some relevant co-variates was observed. Nevertheless, some strengths of this study should be highlighted: (a) the control group was composed of patients under 80 years old with ACS undergoing CA, who attended the same hospital during the same period of time; (b) a detailed description of pharmacological treatment before the index event, at admission and at hospital discharge were included; (c) a precise characterisation of coronary anatomical findings were incorporated; and (d) 1 year follow-up was performed.

ConclusionsCompared with younger patients, octogenarians undergoing CA for ACS presented a higher prevalence of multivessel disease and a lower proportion of culprit lesion revascularisation. Clinical course included a higher incidence of acute heart failure, acute kidney disease, systolic ventricular dysfunction at discharge, and in-hospital mortality. At one year follow-up, ischaemic stroke and death were also more frequent among this group.

Coronary artery disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in older patients. With an ageing population and longer life expectancies, a progressively increasing proportion of patients presenting with an ACS are octogenarian. However, elderly patients have consistently been under-represented in most clinical trials in the field, resulting in scarce evidence regarding the management of ACS in this scenario and these patients being less likely to receive therapeutic management according to guidelines recommendations.

Does it contribute anything new?The present study comprises a large series of ACS in octogenarian patients undergoing CA. The main strengths of our work are the following: (a) the control group was composed of patients under 80 years old with ACS undergoing CA, who attended the same hospital during the same period; (b) a detailed description of pharmacological treatment before the index event, at admission and at hospital discharge were included; (c) a precise characterisation of coronary anatomical findings was incorporated; and (d) one year follow-up was performed.

This investigation has not received any economic support from any public institutions, the commercial sector or non-profit bodies.

Author's contributionsA. Jerónimo: conception and design of the project; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript. Z. Gómez-Álvarez: drafting of the manuscript. T. Romero-Delgado: drafting of the manuscript. C. Ferrera: analysis and interpretation of data. B. Hennessey: revision of the manuscript. F.J. Noriega: revision of the manuscript. R. Fernández-Jiménez: revision of the manuscript. J.C. Gómez-Polo: Analysis and interpretation of data; revision of the manuscript. A.I. Fernández-Ortiz: revision of the manuscript. A. Viana-Tejedor: revision of the manuscript.

FundingThere were no funding sources supporting this study.

Conflicts of interestNone.