Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) are still widely used for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. However, the access to international normalised ratio (INR) determinations is sometimes difficult and the time in therapeutic range (TTR) is not always available. The aim of this study was to design and validate a simple and easy-to-use questionnaire that enables the identification of atrial fibrillation patients with poor quality of anticoagulation.

MethodsThis is a national, multi-centre, observational, and cross-sectional study including consecutive non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients receiving VKA therapy and followed up at cardiology clinics. At inclusion, INR determinations during the last 6 months were analysed to determine the TTR and the ICUSI questionnaire was completed. A TTR < 65% was considered suboptimal.

ResultsA total of 813 patients (55% men, 75±9 years old) were available for the analyses. The mean TTR was 62.2%±20.3% and 427 (52.5%) patients had a TTR < 65%. The final version of the ICUSI questionnaire included 4 questions and the mean ICUSI score was 1.19±1.17. The predictive ability of the ICUSI questionnaire for predicting TTR < 65% was moderate (c-index, 0.707; 95%CI, 0.670–0.740; P<.001). An ICUSI score of 1 showed a sensitivity of 80.8% and a specificity of 45.6%, whereas an ICUSI score of 2 showed a sensitivity of 43.2% and a specificity of 88.1%.

ConclusionsThe ICUSI questionnaire has shown a good predictive performance for the identification of poor TTR in the absence of full access to the INR determinations in atrial fibrillation patients under VKA therapy.

Los antagonistas de la vitamina K (AVK) todavía se usan para prevenir accidentes cerebrovasculares en fibrilación auricular. Sin embargo, el acceso a determinaciones de índice normalizado internacional (INR) es difícil y, por tanto, el tiempo en el rango terapéutico (TRT) no siempre está disponible. Nuestro objetivo fue diseñar y validar un cuestionario simple y fácil de usar para identificar pacientes con fibrilación auricular con mala calidad de anticoagulación.

MétodosEstudio nacional, multicéntrico, observacional y transversal, que incluye a pacientes consecutivos con fibrilación auricular no valvular que reciben terapia con AVK y cuyo seguimiento se realiza en clínicas de cardiología. En la inclusión se analizaron las determinaciones de INR durante los últimos 6 meses para determinar el TRT y se completó el cuestionario ICUSI. Un TRT<65% se consideró subóptimo.

ResultadosSe analizó a 813 pacientes (55% varones, 75±9 años de edad). El TRT medio fue de 62,2%±20,3% y 427 (52,5%) pacientes tuvieron un TRT<65%. La versión final del cuestionario ICUSI incluyó 4 preguntas y la puntuación media fue 1,19±1,17. La capacidad del cuestionario ICUSI para predecir el TRT<65% fue moderada (índice c=0,707, IC95%: 0,670–0,740; p<0,001). Una puntuación ICUSI de 1 mostró una sensibilidad del 80,8% y una especificidad del 45,6%, mientras que una puntuación ICUSI de 2 mostró una sensibilidad del 43,2% y una especificidad del 88,1%.

ConclusionesEl cuestionario ICUSI demostró un buen desempeño predictivo para la identificación del TRT deficiente en ausencia de acceso completo a determinaciones de INR en pacientes con fibrilación auricular en tratamiento con AVK.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia. It is responsible for a great deal of morbidity and mortality, and its complications entail high healthcare costs.1–3

AF significantly increases the risk of stroke and thromboembolism.4 For this reason, antithrombotic treatment is the cornerstone of the management of this arrhythmia. Both European and American guidelines support using anticoagulant therapy according to the CHA2DS2-VASc score, which stands for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 (doubled), diabetes, stroke (doubled), vascular disease, age 65–74, and sex category (female). Despite the emergence of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as an alternative therapy with a more favourable efficacy and safety profile, in several countries the anticoagulant treatment is still based on vitamin K antagonists (VKAs). However, current European guidelines recommend DOACs over VKAs, and if VKAs are used, the time in therapeutic range (TTR) should be as high as possible.1,5 The TTR is often calculated using Rosendaal method as a way to reflect the quality of anticoagulant therapy in patients taking VKAs, which is deemed acceptable if it is > 65%.6–8 However, the therapeutic window for VKAs is narrow, and international normalised ratio (INR) falling outside of the recommended range (2.0–3.0) significantly increase the incidence of thromboembolic and bleeding events.9,10 Therefore, it is crucial to identify those patients on VKAs with poor quality of anticoagulation.

This study intends to design and validate a simple and easy-to-use questionnaire that enables the identification of AF patients with poor quality of anticoagulation in order to perform a more comprehensive follow-up as well as to assess alternatives to prevent potential complications.

MethodsThis is a national, multi-centre, observational, and cross-sectional study of consecutive AF patients on oral anticoagulant therapy with VKAs and followed up at cardiology clinics. The study was designed as non-interventional so the decision of the medical care and treatment was taken at the discretion of the treating physician of each patient. From January 2015 to February 2017, AF patients from 54 sites in Spain were enrolled. The inclusion criteria included patients ≥ 18 years of age with non-valvular AF diagnosed more than 6 months before and receiving VKAs. The INR determinations during the last 6 months had to be accessible for review and the last determination of INR should have been done in the 30 days prior to inclusion in the study. Patients with active cancer, diagnosed with severe/moderate cognitive impairment and patients who had undergone surgical interventions in the last 6 months involving modifications of the anticoagulant therapy that might temporarily affect the INR, were excluded. Patients with prosthetic heart valves or rheumatic mitral valve were also not included.

At inclusion, baseline clinical and demographic characteristics were recorded. During this visits, all patients fulfilled the ICUSI questionnaire. In addition, INR values for all determinations during the last 6 months were analysed in order to determine the TTR. The TTR was evaluated both, according to the linear interpolation method of Rosendaal et al.6 and the proportion of INRs in range. We established the cut-off value for acceptable quality of anticoagulation at TTR ≥ 65%, as recommended by clinical guidelines of both the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Spanish Ministry of Health.11,12 As this was a cross-sectional study, no follow-up was performed.

The study was performed in accordance to good clinical practice guidelines set out in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, Madrid, and the Ethics Committees of the participating hospitals. All patients signed the informed consent for participation.

The ICUSI questionnaireThe ICUSI (Spanish acronym for INR controls, emergency department referral, bleeding and stroke, and heparin injections) questionnaire was designed based on the opinion of an expert panel of study investigators and was conceived as a screening tool to detect patients treated with VKAs with inadequate anticoagulant therapy management in the last 6 months. Initially, the ICUSI questionnaire included 5 questions, with 2–3 possible answers: (1) INR determinations more than once per month (No=0 points; Yes, one month=1 point; Yes, more than one month=2 points), (2) Occasional heparin injections due to low INR levels (No=0 points; Yes, once=1 point; Yes, more than once=2 points), (3) Referred to emergency department due to high INR levels (vitamin K administration) (No=0 points; Yes=1 point), (4) Bleeding requiring visit to the emergency department (No=0 points; Yes=1 point) and (5) Stroke during this period (No=0 points; Yes=1 point).

Statistical analysisThe sample size was determined based on (a) the number of questions included in the ICUSI questionnaire, (b) the minimum size for obtaining stable multivariate estimations, and (c) the representativeness of the sample on a geographic context.

Categorical variables were summarised as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were tested for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate.

The Pearson Chi-squared test was used to compare proportions. Differences between continuous and categorical variables were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test, and correlations between continuous variables were assessed by the Pearson's correlation coefficient.

In order to measure the internal consistency and homogeneity of the ICUSI questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was estimated. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed, using polychoric estimation of correlations and the weighted least squares mean and variance (WLSMV) adjusted estimation method, and assuming a one-dimensional structure (Table 1 of the supplementary data).

A logistic regression model was performed to determine the association between the components of the ICUSI score and the risk of TTR < 65%. Relations between predictor variables and with the dichotomous criteria were assessed using odds ratio Chi-square and Monte-Carlo estimates of significance, in order to avoid problems due to small cell frequencies.

Once the optimal logistic model was obtained, a more suitable scoring procedure was proposed to obtain ICUSI scores, to avoid the use of decimal weights and the exponential function. Anchoring the absence of each indicator at the value of 0 (as it is done in the logistic model) consecutive integer scalars were proposed for each increasing level of severity in the indicators. The simplified scoring method was tested against the optimal logistic scoring, ensuring that a similar scaling ranking was preserved (without inversions).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was applied to evaluate the predictive ability (expressed as c-index) of the ICUSI score. The Youden index was used to determine the score with the best combination of sensitivity and specificity, in order to establish a cut-off value.

A P value < .05 was accepted as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS v. 25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), Mplus v. 7.3 (Muhén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) and MedCalc v. 16.4.3 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium) for Windows.

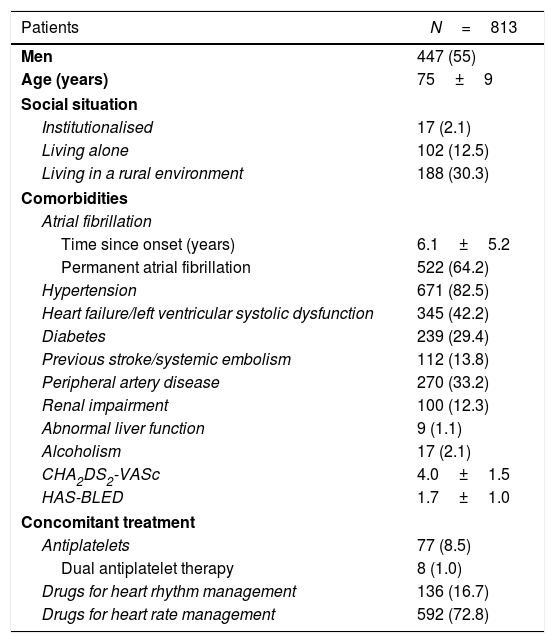

ResultsDuring the recruitment period, 876 patients were initially selected for participation. Of them 63 patients (7.19%) were not suitable for being included since they did not meet any of the inclusion criteria. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 813 patients of which 447 (55%) were males with a mean age of 75±9 years. The mean CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores were 4.0±1.5 and 1.7±1.0, respectively. A brief summary of baseline characteristics is shown in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Patients | N=813 |

|---|---|

| Men | 447 (55) |

| Age (years) | 75±9 |

| Social situation | |

| Institutionalised | 17 (2.1) |

| Living alone | 102 (12.5) |

| Living in a rural environment | 188 (30.3) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Atrial fibrillation | |

| Time since onset (years) | 6.1±5.2 |

| Permanent atrial fibrillation | 522 (64.2) |

| Hypertension | 671 (82.5) |

| Heart failure/left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 345 (42.2) |

| Diabetes | 239 (29.4) |

| Previous stroke/systemic embolism | 112 (13.8) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 270 (33.2) |

| Renal impairment | 100 (12.3) |

| Abnormal liver function | 9 (1.1) |

| Alcoholism | 17 (2.1) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 4.0±1.5 |

| HAS-BLED | 1.7±1.0 |

| Concomitant treatment | |

| Antiplatelets | 77 (8.5) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 8 (1.0) |

| Drugs for heart rhythm management | 136 (16.7) |

| Drugs for heart rate management | 592 (72.8) |

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean±SD (standard deviation).

CHA2DS2-VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 (doubled), diabetes, stroke (doubled), vascular disease, age 65–74, and sex category (female); HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal liver/renal function, stroke history, bleeding predisposition, labile INR, elderly, drug/alcohol usage.

An average of 9 INR determinations per patient (range 4–15) was recorded. The mean period since the patient started VKA therapy was 7.5±2.2 months and the mean INR determinations per month was 1.5±0.5 (range 0.4–5.5determinations/month).

Regarding the quality of anticoagulation, the mean TTR according to the method of Rosendaal was 62.2%±20.3%. Of note, more than half of patients (427, 52.5%) had a TTR < 65%. When the quality of anticoagulation was assessed by the proportion of INRs in range, the mean TTR was of 61.7±20.4%. A total of 366 (45.0%) patients showed a TTR < 60%. The Pearson correlation index showed a high direct correlation between both methods (r=0.752, P<.001).

Responses to the ICUSI questionnaireAll patients completed the ICUSI questionnaire. Regarding the question about the need for occasional heparin injections in the last 6 months, most (82.9%) patients referred that they did not require them, whereas 7.9% required them on one occasion and 9.2% required them more than one occasion. Concerning the INRs determinations frequency, 34.6% of patients needed only one determination per month during the last 6 months, whereas 46.5% of patients needed more than once per month in one occasion and 18.9% needed more than once per month in several occasions. Finally, 2.7% of patients referred that they attended to the emergency room due to high INRs, 4.6% suffered an active bleeding and 0.9% suffered a stroke/systemic embolism in the last 6 months, which indicates the low prevalence of these events in our population.

Final version of the ICUSI questionnaire and predictive abilityTaking the above data into account, the mean ICUSI score was 1.19±1.17, with a minimum of 0 points (31.0%) and a maximum of 6 points (0.1%). The mean score in patients with TTR < 65% was 1.58±1.264 whereas the mean score in patients with TTR ≥ 65% was 0.74±0.845 (P<.001). The TTR negatively correlated with the ICUSI score (r=−0.410, P<.001) i.e., higher scores in the ICUSI questionnaire were related to lower TTR by the Rosendaal method.

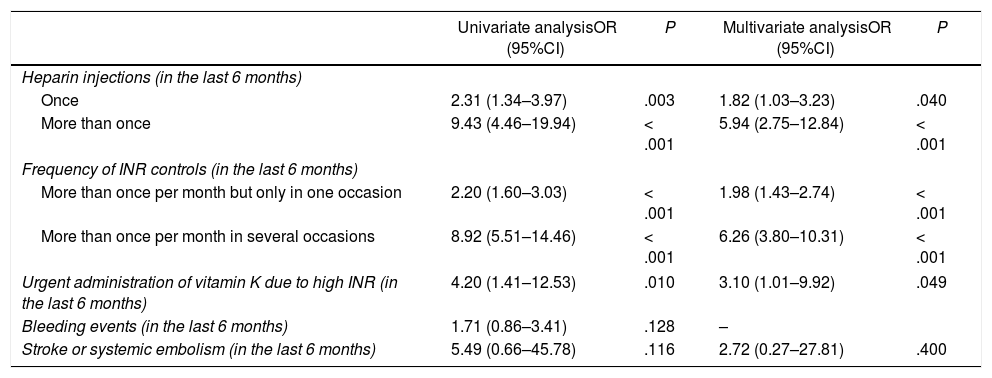

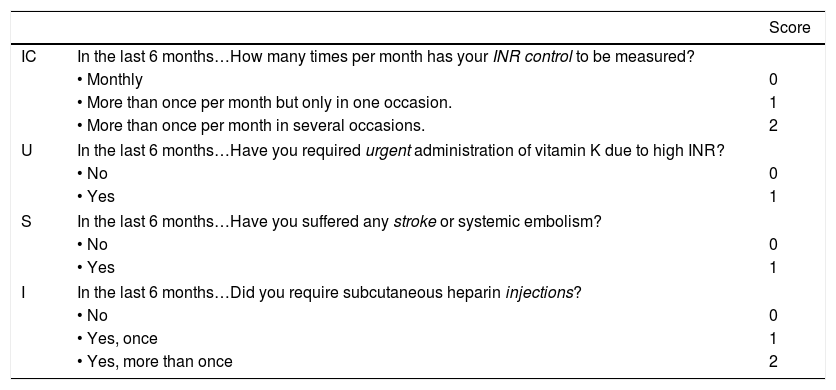

Using logistic regression models, we investigated the association of each question of the ICUSI with the risk of TTR < 65% by the Rosendaal method. The first 3 questions (about heparin injections, INRs determinations frequency and attendance/hospitalizations due to high INRs) yielded significant coefficients (P<.05) in the univariate analysis whereas non-significant coefficients were shown by the questions about bleeding (OR 1.71, 95%CI, 0.86–3.41; P=.128) and stroke/systemic embolism (OR 5.49, 95%CI, 0.66–45.78; P=.116) events. Given that the coefficient for the bleeding events was not significant in the univariate model (albeit it is clinical relevant), this variable was not included into the multivariate analysis and thus, it was excluded from the ICUSI questionnaire. Similarly, stroke/systemic embolism did not achieve significance in the multivariate analysis. However, after the judgment of the study investigators and given the clinical significance that the importance that suffering stroke/systemic embolism events has for the management of the anticoagulant therapy regardless of optimal or poor TTR, this question was retained in the final model (Table 2). Thus, the final version of the ICUSI questionnaire included 4 questions (Table 3).

Association of each ICUSI question and poor anticoagulation quality.

| Univariate analysisOR (95%CI) | P | Multivariate analysisOR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heparin injections (in the last 6 months) | ||||

| Once | 2.31 (1.34–3.97) | .003 | 1.82 (1.03–3.23) | .040 |

| More than once | 9.43 (4.46–19.94) | < .001 | 5.94 (2.75–12.84) | < .001 |

| Frequency of INR controls (in the last 6 months) | ||||

| More than once per month but only in one occasion | 2.20 (1.60–3.03) | < .001 | 1.98 (1.43–2.74) | < .001 |

| More than once per month in several occasions | 8.92 (5.51–14.46) | < .001 | 6.26 (3.80–10.31) | < .001 |

| Urgent administration of vitamin K due to high INR (in the last 6 months) | 4.20 (1.41–12.53) | .010 | 3.10 (1.01–9.92) | .049 |

| Bleeding events (in the last 6 months) | 1.71 (0.86–3.41) | .128 | – | |

| Stroke or systemic embolism (in the last 6 months) | 5.49 (0.66–45.78) | .116 | 2.72 (0.27–27.81) | .400 |

CI, confidence interval; INR, international normalised ratio; OR, odds ratio.

The table shows the association of each question of the ICUSI and poor quality of anticoagulation (i.e. time in therapeutic range < 65%).

Final version of the ICUSI questionnaire.

| Score | ||

|---|---|---|

| IC | In the last 6 months…How many times per month has your INR control to be measured? | |

| • Monthly | 0 | |

| • More than once per month but only in one occasion. | 1 | |

| • More than once per month in several occasions. | 2 | |

| U | In the last 6 months…Have you required urgent administration of vitamin K due to high INR? | |

| • No | 0 | |

| • Yes | 1 | |

| S | In the last 6 months…Have you suffered any stroke or systemic embolism? | |

| • No | 0 | |

| • Yes | 1 | |

| I | In the last 6 months…Did you require subcutaneous heparin injections? | |

| • No | 0 | |

| • Yes, once | 1 | |

| • Yes, more than once | 2 | |

INR, international normalised ratio.

Given the low prevalence, in our sample, of haemorrhagic events (4.6%) and embolic events (0.9%), the statistical power of these variables may have been compromised. Haemorrhagic events were related to the scaling measurement given by Rosendaal TTR, grouped in ten score intervals (χ2=19.6, degree of freedom [df]=9, P=.022), but haemorrhagic events were also related to other predictors (heparin injections: χ2=18.4, df=2, P<.001; INR control frequency: χ2=11.03, df=2, P=.004; hospitalisation by high INR: χ2=60.5, df=1, P<.001), limiting its discriminant power in the multivariate model. On the other hand, embolic events did not exhibit such multicollinearity, being related only to INR control frequency (χ2=9.3, df=2, P=.010).

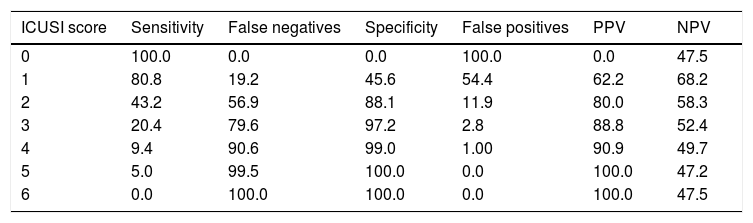

Finally, the predictive ability of the ICUSI questionnaire for the prediction of TTR < 65% was moderate, with a significant c-index of 0.707 (95%CI, 0.670–0.740; P<.001). Different cut-off points were investigated by comparing sensitivities and specificities as is shown in Table 4. Thus, an ICUSI score of 1 yielded a sensitivity of 80.8% and a specificity of 45.6%, whereas an ICUSI score of 2 yielded a sensitivity of 43.2% and a specificity of 88.1%.

Predictive ability of the final version of the ICUSI questionnaire.

| ICUSI score | Sensitivity | False negatives | Specificity | False positives | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 47.5 |

| 1 | 80.8 | 19.2 | 45.6 | 54.4 | 62.2 | 68.2 |

| 2 | 43.2 | 56.9 | 88.1 | 11.9 | 80.0 | 58.3 |

| 3 | 20.4 | 79.6 | 97.2 | 2.8 | 88.8 | 52.4 |

| 4 | 9.4 | 90.6 | 99.0 | 1.00 | 90.9 | 49.7 |

| 5 | 5.0 | 99.5 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 47.2 |

| 6 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 47.5 |

NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

In this national and multicenter study including AF patients under VKA therapy, we have demonstrated that the ICUSI questionnaire, a simple and friendly to use tool, has a good predictive performance for the identification of poor quality of anticoagulation in the absence of full access to the INR determinations.

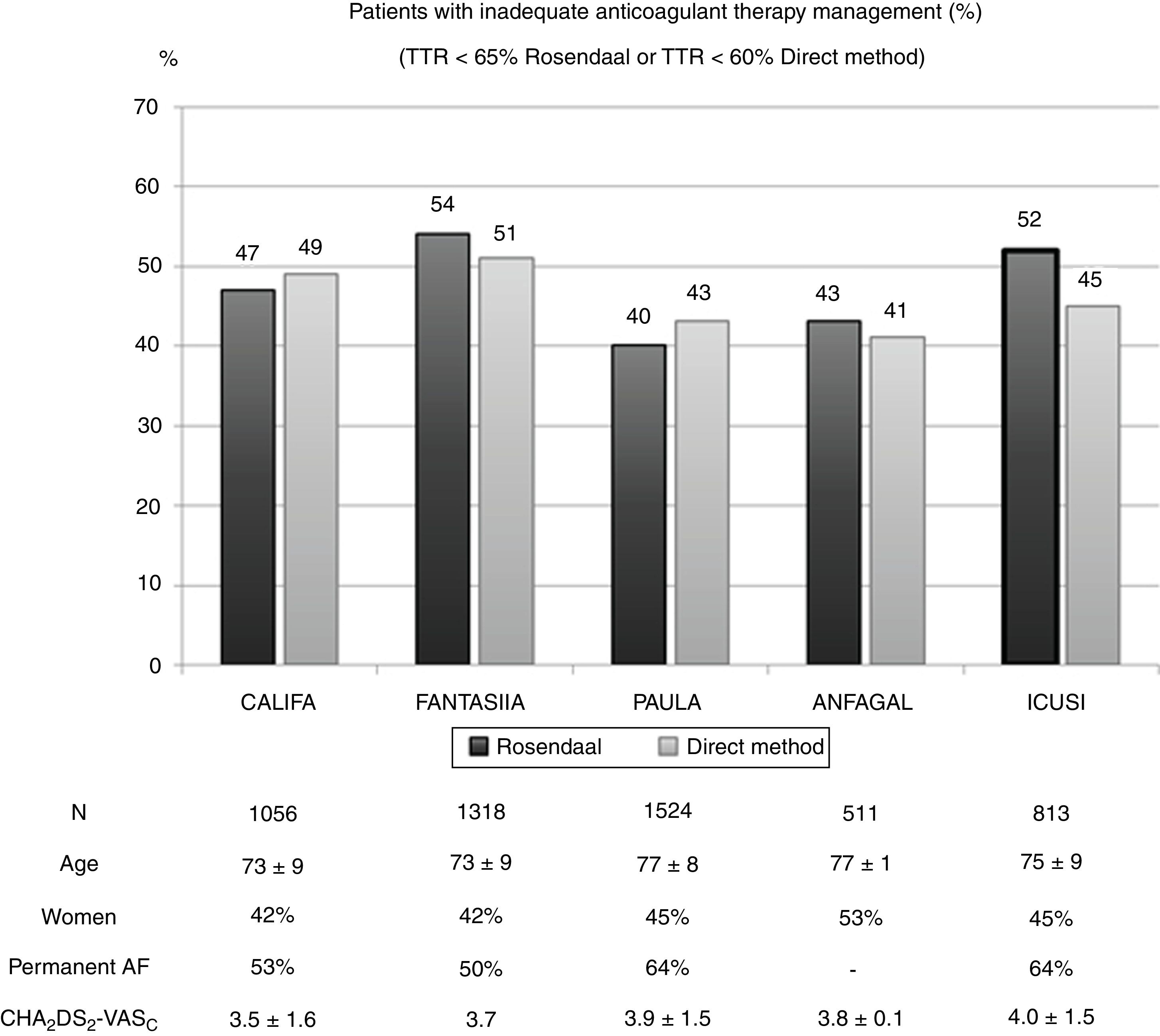

Among AF patients who receive anticoagulant therapy in Spain, around 75% receive VKAs and 25% receive DOACs.13,14 However, given the narrow therapeutic window of VKAs, many patients receiving this therapy have not the optimal TTR. Indeed, the current study demonstrates poor anticoagulant therapy management in ≈ 52% of patients (45% when measured by the proportion of INR in range, see Fig. 1).15–18 Other European studies, including the extensive EURObservational Research Programme on Atrial Fibrillation,19 confirm these data and show an inadequate anticoagulant therapy management in 40–50% of patients.13,15,17,19 DOAC have demonstrated to be at least as effective and even safer compared to warfarin.20–22 Unfortunately, there are still restrictions to the use of DOAC in several countries so VKA are used as a first-line treatment for the prevention of thromboembolism in non-valvular AF. The most common reason for switching to DOAC is an inappropriate quality of anticoagulation in patients taking VKA who have good adherence to treatment and under this circumstances, the Spanish authorities allow clinicians to prescribe DOAC.23

Quality of anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists in different Spanish studies.

AF, atrial fibrillation; CHA2DS2-VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 (doubled), diabetes, stroke (doubled), vascular disease, age 65–74, and sex category (female); TTR, time in therapeutic range.

Nevertheless, the assessment of the quality of VKA therapy is not always easy. Many of these patients are followed-up by Primary Care, Internal Medicine or in Cardiology Clinics,24,25 where INR determinations are often not available. The lack of electronic medical records, lack or limited access to INRs data from the computer, problems with the connexion to internet, and limited time in the clinical practice are just some of the most common problems reported by physicians. For this reason, it is complicated to calculate the TTR and as consequence, many poorly controlled patients remain in VKA therapy.

Therefore, clinical tools are required to detect patients with poor anticoagulant therapy, particularly in the absence of access to INRs determinations.

Previous clinical schemes have been developed with this aim. For example, the SAME-TT2R2 (standing for sex [female], age [60 years], medical history, treatment [interacting drugs, e.g., amiodarone for rhythm control], tobacco use [doubled], race [doubled]) was described for the identification of those patients more likely to have future poor quality of anticoagulation with VKA, and thus it can be aid in the decision making between VKA and DOAC.26 For this reason, this prediction rule is particularly interesting in newly diagnosed AF patients who are going to be treated with oral anticoagulants. On the contrary, the target AF population for the ICUSI questionnaire is already under VKA therapy since several months ago, but the treating physician has not the possibility to assess the TTR. Here, we clearly show that a simple 4-item questionnaire has a significant predictive ability (c-index=0.71) for inappropriate TTR. Indeed, patients with TTR < 65% had significantly lower ICUSI scores and just 31% of patients scored 0 points, which reflects the real daily clinical practice of the VKA therapy.

LimitationsThere are some limitations that we should acknowledge. First, the ICUSI questionnaire has not been developed by investigating variables associated with TTR, but the opinion of experts based on the most common reasons and observations referred by patients in the daily clinical practice. However, this study reflects a population representative of Spain and similar to those of all other observational studies carried out in our country. Second, to date there is no prospective external validation and we consider that it is necessary for the introduction of this tool in the real-life. Finally, it is important to note that the questionnaire was filled in as per the responses provided by patients and thus it based on subjective information.

ConclusionsThe ICUSI questionnaire is a simple and friendly to use tool that has shown a good predictive ability for the identification of poor quality of anticoagulation in a national, multicenter and observational study including AF patients under VKA therapy. This questionnaire could be used as a useful screening tool to identify those patients with poor TTR when the access to the INR determinations is limited or not possible, and that would benefit from a closer follow-up.

- •

AF is responsible for a great deal of morbidity and mortality. VKAs remain the initial therapy for AF patients.

- •

A number of representative European registries demonstrate inadequate anticoagulant therapy management in at least 40% of patients.

- •

Therefore, it is crucial to identify these poorly managed patients and assess the possibility of more effective and/or safer alternatives for them.

- •

ICUSI is an easy-to-use questionnaire that enables identification of patients with poor INR management as reflected by the TTR < 65% using Rosendaal method.

- •

An ICUSI score ≥ 2 during routine clinical visits accurately identified those patients with poor INR control.

- •

ICUSI score efficiently detects patients that would benefit from additional strategies for improving anticoagulation control with VKA or alternative antithrombotic treatment.

This study was sponsored by Pfizer and funded by a non-restrictive grant from Pfizer/Bristol-Myers-Squibb Alliance.

Conflicts of interestI. Unzueta, S. Fernández de Cabo and J. Chaves are Pfizer employees. The rest of authors declare no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank all the study investigators.

Abbreviations: VKA, vitamin K antagonists; INR, international normalised ratio; TTR, therapeutic range; AF, atrial fibrillation; DOAC, direct-acting oral anticoagulants.